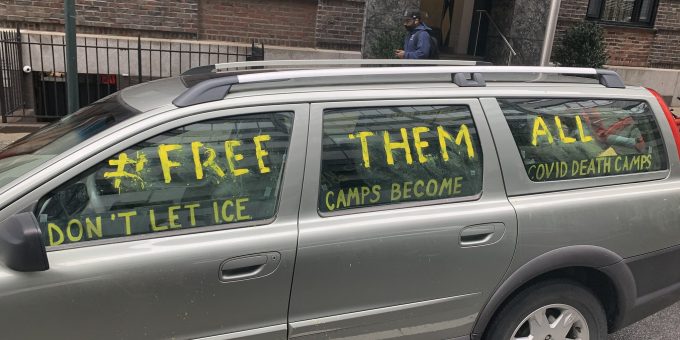

A participant in the #FreeThemAll Car+Bike Rally in NYC, April 24, 2020. Photo by Andrew Ratto, Flickr CC. https://flic.kr/p/2iVqGJc

A Display of White Ignorance in ICE’s COVID-19 Response

As sociologists who study race as it relates to immigrant detention, we see White ignorance as different from ignorance in the more general sense. In line with the dictionary definition of ignorance, someone is “ignorant” because they lack knowledge or are naïve about a particular subject (not because they intentionally engage in harmful practices). In contrast, White ignorance is much less passive. According to political philosophy scholar Charles Mills, White ignorance refers to the active and willful “unknowing” Whites possess about race relations and racial inequality. Mills and others we rely on in our work describe society as deeply “racialized,” meaning that people are treated as more or less valuable depending on their race. This deep racialization results in equally deep racial inequities, yet White Americans actively ignore them within their everyday lives. For example, at many universities, we learn about White contributors through the buildings that are named after them (at North Carolina State, D.H. Hill, Banks C. Talley, and James B. Hunt come to mind), but we don’t learn the names of the people actually responsible for maintaining university campuses, many of whom are non-White. With national holidays, street and park names, monuments, and even standard school curricula following a similar pattern, Americans devalue non-White lives by constantly acknowledging Whites’ presence and placement in society while “unknowing” the essential role of racial minority groups in the United States.

The consequences of this active racial unknowing are profound. As sociologist Jennifer Mueller explains, White ignorance “surround[s] White privilege, culpability, and structural White supremacy.” In other words, White ignorance supports the current racial status quo. Notable news stories from the past several months show how diverse this support can be, from doubt that police violence against Black Americans committed by Black officers perpetuates racist law enforcement to support for racial segregation as a peacekeeping strategy. And while White ignorance includes obvious racial bigotry reflected in individuals’ statements and actions, it also operates more subtly within institutional practices. During our review of 631 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) news releases from 2020, we found a striking example of this institutional White ignorance: ICE’s silence on immigration detention and emphasis on fraud in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.“What about Immigration Detention?” ICE’s COVID-19 Response

“‘It was like a time bomb,’” Yudanys, a detained Cuban immigrant, told the New York Times. But Yudanys wasn’t alone. Kanate, a detained refugee from Kyrgyzstan, explained, “‘I was panicking. I thought that I will die here in this prison.'” The data we found supports their desperation. According to a report from Freedom for Immigrants, about 60% of all COVID tests performed in ICE detention centers by April 29, 2020 were positive. Media outlets and advocacy groups began calling attention to this situation early on. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) urged ICE to “reduce the number of people in detention, starting with the most vulnerable, to keep them safe from COVID-19 before it is too late.” With concerns like these filling majorities of the March and April articles on immigration detention from the New York Times (about 94%) and the ACLU (about 75%), pandemic-era media coverage pushed ICE to address detention-related health risks.In functioning democracies, governmental agencies should be accountable to the public. However, this type of accountability is not what we found in ICE’s pandemic response. Rather, the most striking pattern is what we did not find within ICE’s news releases—what sociologists call a patterned absence. Only 49 of the 631 news releases, or about 8%, even mentioned COVID-19. This means that, in a year where the pandemic was at the center of global attention, ICE spent only a small portion of its press even acknowledging that pandemic. Thus, ICE’s primary strategy during the initial year of the pandemic was avoidance.

So, what did we observe ICE discussing among the scant 8% of news releases about COVID-19? The agency mainly introduced and promoted a new type of enforcement campaign: Operation Stolen Promise. In an April 2020 news release, ICE explained the operation as a “collaboration with multiple federal departments and agencies, along with business and industry representatives” intended to “combat COVID-19 related fraud and other criminal activity.” Prior to the pandemic, ICE’s discussions of counterfeit merchandise accounted for about 3% of its news releases that year. However, references to Operation Stolen Promise specifically or counterfeit COVID-19 merchandise more generally appeared in approximately 49% of ICE’s news releases on COVID-19 that year. By highlighting this operation, ICE abandoned the role of an immigration enforcer to portray itself instead as a heroic protector against COVID-19 fraud. In doing so, the agency avoided providing a justification for its detention of migrants during the pandemic.

What about White Ignorance? Analyzing ICE’s Response

We view ICE’s framing of immigration detention, or lack thereof, during the pandemic as a powerful example of institutional White ignorance, given that most migrants detained by the United States are people of Latin American descent. The agency’s reluctance to take responsibility for COVID-19 transmission within its detained populations contributed significantly to the vulnerability of migrants in its custody. And, by not addressing how COVID-19 impacted detained migrants despite the media attention on the subject, ICE actively engaged in ignorance that showed an extreme lack of compassion toward an oppressed group. To be clear, ICE’s pandemic response was not just a public relations spin in response to bad press about immigration detention, as we have seen the agency use when facing past scandals. Instead, we witnessed ICE nearly abandon updates on immigration detention altogether as one of its responsibilities during the pandemic.

The agency’s practices negatively affected detained migrants. Of course, the agency did not openly endorse policies benefitting White Americans and harming people of color; instead, it implied support for racially inequitable policies through subtle yet strategic omissions in its descriptions of pandemic-era immigration detention and uncharacteristic diversions like Operation Stolen Promise. Just as Americans regularly “unknow” the contributions of non-White communities through building and street names, we observed ICE “unknow” the ways it harmed the people it detained, the majority of whom are non-White, by emphasizing the need to stop “COVID-19 fraud” rather than to minimize COVID-19 transmission risks.

Since government institutions like ICE keep racial inequality alive through White ignorance, it is essential to consider what can be done to lessen this active “unknowing.” From our broader analyses of immigrant detention, we understand practices like ICE’s COVID-19 response to be part of the U.S. government’s greater dependency on White ignorance. Changing radical dependency ultimately requires a radical intervention: a wholesale alteration of the government. But a change this large must start on a smaller scale. For instance, everyday White Americans can intentionally attune themselves to the life experiences of people of color rather than accepting the images government and other institutions present of non-White racial groups without question.Since government institutions like ICE keep racial inequality alive through White ignorance, it is essential to consider what can be done to lessen this active “unknowing.”A functioning democracy relies on government officials being accountable to the people they represent. While we, the people, cannot end White ignorance ourselves, we can start the process. Assuming we still live in a functional democracy, government change will follow.

Joshua R. Hummel is a Ph.D. candidate in the Sociology and Anthropology Department at North Carolina State University. His research explores the discursive construction of difference and racial identity. Emily P. Estrada is an Assistant Professor in the Sociology Department at State University of New York at Oswego. Her research investigates the implicit racialization of Latinx immigrants through cultural and institutional discourses.

Comments