Understanding “Occupy”

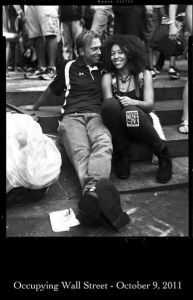

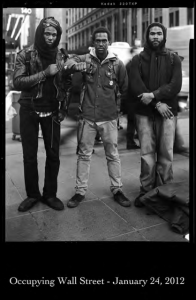

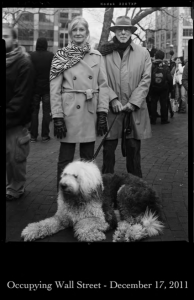

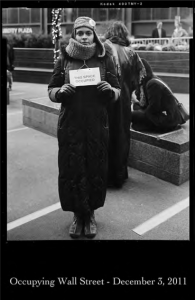

Last fall, an extraordinary upsurge of protest burst onto the streets of lower Manhattan, and quickly rippled across the nation. In Zuccotti Park, ground zero for the movement—which lay in close proximity to the “other” ground zero—an oppositional community comprised of hundreds of activists (and a library, kitchen, theater, and medical and legal teams) formed practically overnight.

The neighborhood where financial traders ply their trade became the stage for dissidence of a sort that we have not seen in this country for a very long time. There one could witness—and quickly become a part of—dozens of simultaneous small group conversations about student debt, veterans’ post-traumatic stress, or the complexities of credit-default swaps, “fracking,” and more. Nightly meetings, called general assemblies, were like New England town meetings with an anarchist edge, marked by youthful exuberance and the sense that here was history-in-the-making.

The protests went into hibernation, thanks to the efforts of city governments from New York to Oakland to break them up. But, at this writing, efforts to regroup are now underway.

We asked experts, representing a range of perspectives, to comment on the “Occupy” movement and its significance. How can we account for its sudden emergence? What are its distinctive characteristics, its intellectual and social roots, and its likely future? Together, they offer a lively set of commentaries that help us to make sense of this moment of rage and hope.

- Revolt of the College-Education Millenials, by Ruth Milkman

- What Democracy Looks Like, by Benjamin Barber

- The Global Culture of Protest, by Mohammed A. Bamyeh

- A New Public Rhetoric for the Occupy Movement, by William Julius Wilson

- The Anarchist DNA of Occupy, by Dana Williams

- Occupy’s Political Emotions, by Deborah B. Gould

Revolt of the College-Educated Millenials

by Ruth Milkman

The Occupy Wall Street movement is, above all, a generational phenomenon. Like its counterparts around the globe, from Madrid to Cairo, to Tel Aviv to Moscow, many of the OWS protagonists are highly-educated young adults in their twenties and early thirties. The movement rapidly attracted adherents from a far more diverse population, but the key demographic driving its initial ascent in the fall of 2011 was college-educated “millennials,” the baby boomers’ offspring.

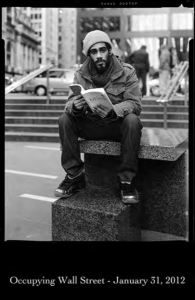

The OWS activists’ high level of formal education is also significant from another angle. They followed the prescribed path to prepare themselves for professional jobs or other meaningful careers. But having completed their degrees, they confronted a labor market bleaker than anytime since the 1930s. Adding insult to injury, many were burdened with enormous amounts of student debt.

In this sense, Occupy might be seen as a classic revolution of rising expectations. But it is not only about blocked economic aspirations: The millennials were also seduced and abandoned politically. Their generation enthusiastically supported Barack Obama in 2008; some participated in “Camp Obama,” and many were otherwise actively involved in the campaign. But here, too, their expectations were brutally disappointed. When a group of (slightly older) veteran direct action activists opened up a different political path, the millennials were primed to explore it. They embraced “horizontalism,” a form of of consensus-based participatory democracy that is inclusive and anti-hierarchal, as well as a “prefigurative politics” that aims to foreshadow a democratic social practice inside the movement itself. Both horizontalism and prefigurative politics are now widely viewed as OWS trademarks.

With an unintended boost from the overreaction of the New York Police Department to the occupation of Zuccotti Park, OWS garnered enormous attention in both conventional and “social” media. As it riveted public attention worldwide, the movement rapidly spread to every corner of the United States as well as to new venues abroad. It was not long before key labor unions and other progressive organizations stepped up to support OWS with both financial and logistical resources. (However, these pale in comparison to the funding the Koch brothers and others in the “1 percent” provide to the Tea Party, to which Occupy is sometimes compared.)

Although some observers were perplexed by the movement’s lack of conventional “demands” or a single “message,” OWS captured the imagination of the wider public. Its deceptively simple slogan, “We are the 99 percent!” raised popular awareness of the issue of economic inequality, stoking the moral outrage of ordinary citizens and transforming the national political conversation. The movement also deserves credit for a flurry of modest policy concessions: for example, extending the New York “millionaires’ tax,” which had been set to expire at the end of 2011.

The coordinated evictions of Zuccotti Park and various other encampments across the country made the strategic importance of those spaces more salient than before they were surrendered. Their loss, along with internal divisions that have, not surprisingly, emerged within the movement, has generated some uncertainty about the future. But whatever shape it assumes in the coming months and years, OWS seems destined to have a lasting impact on American politics and culture, like its counterparts around the world.

What Democracy Looks Like

by Benjamin Barber

In this Presidential election year, when the two parties are drawing further apart, it may be the decisions that OWS makes about national politics and participation in the elections that determine the future of our nation. For above all, OWS, like the Tea Party, is channeling anger at inequality and injustice. More like philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau than the Tea Party, however, OWS turns anger to constructive civic purposes. It distrusts the patter of politicians about democracy as one more transparent attempt to “throw garlands of flowers over our chains.” To be authentic, democracy must be palpable, participatory, local—like Occupy Wall Street itself.

If the myriad and varied denizons of this profoundly democratic movement decide to manifest their convictions politically and take a stand at the polls, they will contribute to revivifying democracy. If they withdraw from politics, and sit the election out while insisting that the differences between the parties and candidates are marginal and the similarities overwhelming, our democracy will be even worse off—whoever triumphs in the polls.

Understanding what OWS is as a political movement is therefore crucial. OWS certainly has an inclination to political commitment; but it also is skeptical about the political realm. OWS dismisses American democracy as a fraud—and sees politicians as just as corrupt and wayward as the bankers and corporate CEOs who have been buying them. At the same time, it holds up its own existence as a model of “what democracy looks like.”

To be sure, the occupiers, with their multi-hued cornucopia of perspectives, are a diverse lot. The many encampments embrace a panoply of causes, and contain tensions and fissures the protesters themselves acknowledge and even welcome. OWS has become a vessel into which people pour their own fears and aspirations. That is not to say there is no unifying theme. It’s “Occupy Wall Street” not “Occupy the Times Square military recruiting station” or “Occupy Gracie Mansion.” It’s about the MONEY, stupid–the money that replaces votes (the people) with dollars (the plutocracy). Money, OWS recognizes, has unraveled the social contract. The occupiers may not have demands, but they do have an agenda. It is their powerful process that speaks to their principles.

Their process is a bold attempt to embody an alternative paradigm of participatory engagement, suggesting that the protesters, so cynical about democracy, have figured out how to practice it. What the process offers is a compelling rejection of the instrumentalism so beloved of American politicians — “the end justifies the means.” President Obama has to raise funds from big-time bundlers and lobbyists (despite his pledge not to do so) — how else can he get reelected? Off-shore drilling may risk cataclysmic environmental disaster but we need the jobs and independence from foreign oil. The protesters’ principles, in contrast, are in their processes, and the processes are quite remarkable — not only for the contrast they offer to how we normally conduct business, but for how well they actually work.

The key process requires that all decisions — whether about tactics or money expended, or principles or changes in structure — be submitted to the General Assembly (GA), which then convenes almost every day and is the source of the movement’s “general will,” and its legitimacy. The GA’s process is maddeningly open, transparent, and changing.

Cynics on the right dismiss OWS as a bunch of crazies and collectivists, but I know of no democratic process so attuned to the autonomy and rights of individuals. Indeed, one of the serendipitous features of the process is the “people’s microphone” — an innovation necessitated by the refusal of the city to allow electronic voice amplification. With crowds of several hundred or more at the GA, individual voices cannot be heard, so speakers voice their concerns in snippets that are repeated by the crowd at least once, and sometimes twice, in an expanding circle.

The “people’s microphone” is a clumsy process that makes complex and nuanced speech difficult. But it forces relatively straightforward speech that enhances clarity and communication; and it requires that in dealing with naysayers and “blocks,” the majority must mouth and voice the actual words of those who disagree. How better to kindle sympathy for minority voices than for their majority opponents to rehearse their protests, word for word, and even mimic their affect? How fitting that a movement wedded to moral protest should be attuned to protests from within.

OWS may be naive and exasperating in its refusal to engage in ordinary politics and its initial disdain for voting, especially in this primary silly season where it is apparent how much is at stake. Yet the occupiers know that American anger, right and left, runs deeper; that there is something intrinsically wrong with how we do business. It has impaired leadership and undermined democracy.

Democracy itself is in deep trouble, and so America is in trouble. Occupy Wall Street speaks as our civic conscience. We need the angry deputies of the “99” in politics this year. But we cannot demand that they become more like us. We must become more like them.

The Global Culture of Protest

by Mohammed A. Bamyeh

A new global culture of protest began to take shape in 2011. It first appeared as a series of spectacular revolts in the Arab world, and soon inspired protest movements elsewhere. Each movement faced a distinct local environment. But as a whole these movements display at least six common features: they are the defining elements of a new global culture of protest.

First, the explicit target of this culture of protest is corruption. From the point of view of the protestors, the “system” (whether democratic or not) answers to special, if not secretive, interests, rather than to a popular will. The clearest signs of this corruption of political life is the unapologetic collusion of financial and political power.

Third, and perhaps as a result of the preceding, the protest movements are suspicious of parties and organizations in the traditional sense, as well as of leaders. They display a clear preference for loose networks and experimental structures. The protests derive a sense of direction not from hierarchy, or from a clearly elaborated common ideology, but from the energy of the protest itself, and by the discovery of others who share a similar world perspective. Disgruntled youth are the largest base of the protest; youthfulness and spontaneity becomes a metaphor for the desired rejuvenation of politics.

Fourth, all of these movements reject the idea, put forth by ruling parties or elites, that there is “no alternative,” that genuine opposition has disappeared in formal political life. They oppose the claim that global challenges tie the hands of leaders, and that genuine alternatives are incompatible with democratic process.

Fifth, this global culture of protest claims to address the interests of “the people” as a whole, or at least the 99 percent, or some super-majority, rather than the interests of a specific class (say, the working class). The Arab revolutions were all carried out in the name of “the people,” and this slogan seems to have migrated everywhere, summing up a demand to rejuvenate political life. “Peoplehood” (rather than specific disadvantaged sub-categories) stands opposed to governing systems.

Finally, in this global culture of protest, protesters’ demands possess an enticing vagueness. While this vagueness may make the protest less focused, it also makes it more attractive for the purpose of expressing indignation at the system as a whole, and from various points of interest. Participants appear to tolerate this vagueness because it provides their movement with a sense of experimental youthfulness and conversational conviviality.

We live in exceptional times. The year 2011 may be remembered as the year where various protest movements around the world took form without complex ideological language, and did not seem to be in a hurry to discover a new ideology to express the multiple interests that constituted them. They mobilized around a collective opposition to the “system” in the name of general abstraction — ”the people.” The little person, in whose face a large and unresponsive system had placed a “no alternative” sign, feels the need to respond by doing something great and noble. The birthplace of the new global culture of protest can be identified with precision: Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, on December 17, 2010.

A New Public Rhetoric for the Occupy Movement

by William Julius Wilson

The Occupy movement has accomplished one very important goal—it has raised public awareness of the growing economic inequality in the United States. However, despite this worthy accomplishment, the movement has to yet to develop a vocabulary that helps ordinary Americans understand the legacy of rising inequality. I believe that the future impact and trajectory of the Occupy movement will be limited unless it develops a more comprehensive public rhetoric to help ordinary Americans understand how global economic changes, as well as monetary, fiscal, and social policies, have increased inequality.

The public rhetoric should inform or remind Americans that between 1947 and 1970 all income groups in this country experienced economic advancement. In fact, poor families recorded higher growth in annual real income than other families. However, in the early 1970s this pattern changed. The families in the highest income groups continued to enjoy steady income gains, adjusted for inflation, while the remaining families, especially the lowest 40 percent, experienced declining or stagnating incomes. What was unique about the 1950s and ’60s is that the government’s policies were integral to the gains experienced by all families. Low-wage workers benefited from a wide range of protections, including steady increases in the minimum wage, and the government made full employment a high priority. There was also a strong union movement that ensured higher wages and more non-wage benefits for ordinary workers.

However, in the 1970s and ’80s things moved in a different direction for ordinary workers. The union movement began its downward spiral and macroeconomic policy was no longer geared toward tight labor markets. Monetary policy became dominant, and it was focused on defeating inflation above all else. Beginning with the Reagan experiment, the tax structure became more regressive and Social Security taxes increased. Furthermore, congressional resistance to raising the minimum wage and expanding the earned income tax credit threatened the economic security of disadvantaged families.

History shows that trends of rising inequality are associated not only with economic changes, but also with the eroding strength of what the economist Frank Levy of M.I.T. calls “the nation’s equalizing institutions”—public education, unions, the welfare state broadly defined, international trade regulations, and so on. These equalizing institutions were much stronger from 1947 to 1970 than they are today. To combat rising inequality, the public rhetoric of the Occupy Movement should focus on the need to strengthen these equalizing institutions to produce a more equal pattern of family economic progress in the new economy.

The Anarchist DNA of Occupy

by Dana Williams

Occupy has drawn inspiration from many of 2011’s insurrectionary episodes, including Egypt’s Tahrir Square, Spain’s indignatos, and Puerto Rico’s student strikes. Also important has been Latin America’s horizontalism and zapatismo. But, the most immediate inspiration for Occupy is anarchism. This should surprise only the oblivious: many activists have noticed that American youth are influenced by anarchism more than by Marxism. The first manifestation of this influence is the emphasis upon anti-authoritarianism. There are no leaders (or, more radically, everyone is a leader). Anti-authoritarianism gives Occupy a strength and resilience not enjoyed by most movements. Like a multi-headed hydra, when Occupy’s enemies attempt to chop-off one head — arrest a certain individual — others take their place. No one is in a position to order anyone else around — everyone must participate in all decisions. Corporate media simply can’t understand this paradigm and it’s frustrated by Occupy’s disavowal of spokespersons.

Occupy’s next debt to anarchism is a procedural structure and aesthetic. For OWS, direct, participatory democracy is the order of the day. Lacking official leaders, consensus-building is the only feasible option. Every General Assembly (GA) attendee must be able to accept a decision. The task is assisted by multiple working-groups that meet regularly to discuss nitty-gritty issues. Facilitation guarantees that everyone’s voice is heard, and hand-gestures visually involve everyone. These techniques have popped-up in countless post-1960s anarchist projects. The results of this process can be seen in leaflets circulated at Occupy Oakland, characterizing several of the GA decisions as anarchistic in character: rejection of government endorsements and political parties, equal treatment of GA speakers, preventing police from entering the encampment, and solidarity with striking workers and students.

The movement’s militancy derives from its name. In contrast to other movements, Occupy attempts to reclaim public space, to confront others with its presence, and to stay in the news. Its impatience with polite lobbying or voting has an anarchist flair. Historically, anarchists have encouraged citizens to seize (and decentralize) political power, peasants to occupy private estates and collectivize them, and workers to take over the means of production. Occupy plays with anarchist notions of expropriation and seizing ill-gotten property for individual and collective needs.

Occupy has already enjoyed many victories, convincing countless people of the potential for radical social change. The mass media is now running stories on capitalism, social inequality, and direct democracy. Someone ought to thank Occupy for accomplishing in a few short months what sociologists have been unable to achieve over decades.

Occupy’s Political Emotions

by Deborah B. Gould

“Home” addressed those camping out, but I also read it as a proposition that anyone participating in Occupy was leaving behind the comfort and security that derive from familiarity and knowing what to expect. “Life,” in contrast to home, throws curve balls and is unpredictable. The welcome seemed like an invitation to inhabit the uncertainties entailed in activism— perhaps Occupy activism in particular — and asserted that this direct, engaged mode of politics would rejuvenate and even electrify those who participate.

Uncertainty: one of the Occupy movement’s notable qualities is participants’ appreciation for the fact that nobody knows precisely “what is to be done” to bring about fundamental social change. Political activism often means moving beyond what seems possible into an as yet unknown. It requires thinking and feeling your way, collectively, without a blueprint, embracing experimentation and improvisation, and realizing that mistakes, alongside learning, will necessarily occur. While the ambiguities of activism seem to generate anxiety among commentators who cannot understand what this movement is about, Occupy participants themselves seem able to inhabit that perhaps destabilizing, but also exhilarating emotional state.

Feeling alive: social movements are sites of collective world-making, spaces in which the ongoing interactions of participants produce sentiments, ideas, values, and practices that manifest and encourage new modes of being. Direct democracy is laborious, but Occupy participants exude excitement, even euphoria, suggesting how motivating it can be to engage in collective self-governance and develop new social relations, to come to know your own and other’s intelligences and capacities, and to be changed while building new worlds. Welcome to life.

Occupy illuminates something else about political emotions as well. With its critique of corporate intrusion into politics and with its practices of direct democracy and consensus decision-making, this movement forces a reappraisal of a conventional understanding of the American public as politically apathetic. The mushrooming of the Occupy movement within weeks of its emergence and its garnering of widespread, even mainstream support, suggest that a more familiar political detachment might signal precisely what it is assumed to lack: political desire—a desire, for example, that the state and its representatives speak to people’s needs, wants, and imaginations, and disappointment that they infrequently do so.

Rather than indifference, high rates of non-voting and a more general political withdrawal might better be understood as a response to the ineloquence of the political. By ineloquence I mean non-address: politicians rarely seek to understand and, more rarely still, attend to, people’s desires to create a better society. The Occupy movement invites a different, more active relationship to the political. The enthusiastic response reveals a widespread desire for political engagement. As noted in a piece of Occupy agitprop, “They say we don’t know what we want, but here we are making our decisions without bankers or politicians intervening in our lives. This is what we want.” Once people taste the joys of collective self-governance and sense the possibilities unleashed by becoming political protagonists, they may want more. We do not yet know what has been made possible in this moment of expanding political horizons.