Black and Blue

Chicago, once pejoratively described as America’s Second City, became the first city to offer monetary reparations to victims of police torture. The brutality, which took place between 1972 and 1991, was macabre: beatings, electric shocks, suffocation, mock executions, and other abuses. Under the direction of Jon Burge, a former detective, police officers exacted false confessions that resulted in long prison sentences, even placing some on death row. The hundred-plus victims were mainly African American, and the violence was baldly racial. A cranked device used to electrocute victims was painted black and called the “n—– box.” Nooses dangled from the South side building’s basement ceiling. The City Council’s use of the word “reparations” thus held a particular meaning.

In announcing the agreement, Mayor Rahm Emmanuel spoke of righting wrongs and of bringing “a dark chapter of Chicago’s history to a close.” But it was a belated and reluctant reckoning, a poorly kept secret that the city had spent close to $100 million investigating and settling. “We are gratified, that after so many years of denial and cover-up by the prior administration, the city has acknowledged the harm inflicted by the torture and recognized the needs of the Burge torture survivors and their families by negotiating this historic reparations agreement,” Joey Mogul, an attorney representing many of Burge’s victims, told USA Today. “This legislation is the first of its kind in this country, and its passage and implementation will go a long way to remove the longstanding stain of police torture from the conscience of the city.”The reparations ordinance provides a fund of $5.5 million for torture victims as well as psychological counseling and job assistance. A memorial will be constructed, and the sordid episode will be included in the high school history curriculum.

Chicago is hardly alone in its struggles. Police violence is a grotesquely routine feature of American life, as one city after another is roiled by protests following the killing of yet another unarmed black citizen. There is pressure on Cleveland and Ferguson to put their policing houses in order following the killings of 12-year-old Tamar Rice and 18-year-old Michael Brown. In New York City, the chokehold death of Eric Garner and the shooting of Akai Gurley revive memories of Amadou Diallo and Sean Bell, among others. After killing Walter Scott, who fled a traffic stop in North Charleston, South Carolina, Patrolman Michael Slager laughed about the adrenaline rush he felt.

Deaths are only the beginning. Each botched investigation, each farcical grand jury, each indictment not handed down is more than salt poured onto an already festering wound. It is to open a fresher, deeper gash. By comparison, Baltimore’s decision to indict four officers over the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray, who sustained fatal spinal injuries while in police custody, seems positively revolutionary.The pieces that follow explore the tangled web of race, policing, and justice in America, with a view toward healing. Elliot Currie examines the societal devaluation of Black lives. This is revealed not only in the racial focus of police violence—Black men make up about 6.5% of the U.S. population but 29% of the police deaths so far this year—but also in the collective refusal to address longstanding patterns of discrimination and institutional racism. Katherine Beckett reports on commonsense reforms by the Seattle Police Department, itself under a Justice Department consent decree for the use of excessive force. Sudhir Venkatesh suggests we discard simple oppositions like “us and them” in understanding police-community interaction, foregrounding the role of community “brokers” who mediate relations between citizens and institutions of power. And lastly, Laurence Ralph considers Chicago’s blue light system and its connection to other forms of police surveillance, violence, and control. He suggests the police’s panoptic gaze be turned on itself as an initial step in repairing the broken contract between police and those they are sworn to protect and serve.

— Shehzad Nadeem

- Cops and Brokers, by Sudhir Venkatesh

- The Secret of the Blue Light, by Laurence Ralph

- Shouldn’t Black Lives Matter All The Time?, by Elliott Currie

- Toward Harm Reduction Policing, by Katherine Beckett

Cops and Brokers

by Sudhir Venkatesh

I recently finished a two-year stint as a Senior Research Advisor in the Department of Justice. I’ve also studied crime and policing for over a decade in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. An aspect of contemporary discourse on policing that always perplexes me is the strong dichotomy drawn between “cops” and the “community.” The former typically refers to the institution of law enforcement, possessor of a monopoly on the use of force; on the other side are the civilians, whose role in enforcement is alert bystander. The dichotomy acquires particular poignancy when considering the harsh, sometimes abusive, often neglectful, treatment of Black Americans by police officers.Curiously, when we look at the sociology of policing and criminal justice, this polarity has very little empirical support. The institutional field of social order maintenance demonstrates a much more nuanced set of relations, among a diverse group of actors who are invested in maintaining the peace and addressing conflicts. A clergy member is as likely to respond to disputes as a cop; a school official or block club president may mete out justice rather than a judge; and a social worker or local conflict mediator, instead of a detective or police official, may investigate cause and circumstance. These brokers are absolutely essential in keeping their communities intact. And yet they are glaringly absent in discussions about community-police relations.

Why is it that we prefer the simplicity of such juxtapositions when the world out there is less neat? Consider Elijah Anderson’s book Code of the Street and the more recent On the Run, by Alice Goffman. The power of these two excellent ethnographies lies in taking a messy world and disciplining it simply. Anderson follows the lead of inner city residents who divide their social world into two—usually as a means of placating journalists and social scientists. “Street” and “decent” come to typify people, their values, and their actions. (You can probably guess which side of the divide the cops fall on). The notion of a law-abiding population (and their cops) taking on a criminal element becomes the foundation for Anderson’s eponymous analytic heuristic. Similarly, Goffman writes that there are two types of people in the ghetto: “clean” and “dirty.” Her framework mimics Anderson’s: “The designations of clean and dirty… attach to individuals or locations over time…. [They] become significant even when a police stop isn’t imminent because they are linked to distinct kinds of behavior, attitudes and capabilities.”

The beauty of these dichotomies comes with costs. It becomes difficult to reconcile this narrative with the evidence that suggests police are only one of several important agents of order maintenance. As Peter Moskos shows in his illuminating ethnography of policing in Baltimore, Cop in the Hood, an officer has much less agency than we might imagine. She is subject to the dynamics of local social structure, in which a wider range of actors holds power in matters of crime and justice. Of particular importance is the role of the broker in mediating the relationships of cops and residents. These persons typically do not have adversarial relationships with police. Instead, they help de-escalate conflict, often so that police can investigate effectively. They may work closely with police to broker truces and settle conflicts—thereby giving cops enough time to build up some legitimacy for their own presence. And, they may be the frontlines of communication so that future crime and delinquency can be effectively deterred.

The net effect is two-fold. Police are assured that the interests of some members of the community are aligned with their highest priority: to control and contain the effects of criminal actions. Police also feel that some of their power is diminished by this shared authority. At times, the dynamic leads to heightened frustration for cops unable to influence behavior in ways that they desire.Of course, this may not be a bad thing. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the uncompromising sanctimony of police often undermines the efforts of residents in low-income neighborhoods to keep their lives moving as best they can. Residents work off-the-books to make ends meet, and no amount of police preaching will stop either the need or the practice.

For better and worse, matters of policing are never black and white. A valuable contribution may be to bring the sociology of order maintenance into these shades of grey.

The Secret of the Blue Light

by Laurence Ralph

About every half mile, lampposts mounted with police cameras, encased in plastic domes, loom above the street. Atop the police cameras, a florescent blue light flashes—a siren that can be seen but not heard. In urban Chicago, it is said that the persistence of that silent blue light, its relentlessness, can transform a person.

Chicago’s blue light system exemplifies a faith in policing that exposes just how misleading the notion of “objectivity” can be. Blue lights are technologies whose instrumental function is to collect evidence and deter crime. The irony is that there can never be irrefutable evidence to show that blue lights accurately gather evidence or are an effective crime deterrent. Many criminologists have lamented the reasons why this is true: 1) The blue light system has been implemented with no “control” neighborhoods. Thus, in high crime communities, there are few areas left without cameras to compare against areas that have them; 2) Many blue lights have malfunctioned, yet there is no system for identifying which cameras are working properly; and 3) there are not enough police staff to monitor the blue lights that actually do work.

More than locating crime, then, blue lights serve another social function: to reaffirm, and preserve, the power of the law for the law’s own sake. As the everyday embodiment of State authority, blue lights are indicative of the primary objective of policing—to minimize crime and capture dangerous subjects. Yet, in urban Chicago, residents often argue that blue lights are a pretext for a wider desire for social control at the expense of particular populations. For them, the public secret that the blue light embodies is the larger history of police violence that still plagues them today.In February 2015, for example, The Guardian broke the story of a “domestic black site” in Chicago. In an abandoned warehouse on the South Side of the city, police officers kept criminal suspects out of the official booking database, beat them severely, and denied their access to lawyers for between 12 and 24 hours. At least one man was pronounced dead after he was found unresponsive inside an interrogation room. In the few months since the black site gained national attention, a number of attorneys have stepped forward, claiming that for years, the facility has been a public secret.

“Back when I first started working on torture cases and started representing criminal defendants in the early 1970s,” said Flint Taylor, the attorney who has won millions of dollars on behalf of police torture victims in Chicago, “my clients often told me they’d been taken from one police station to another before [being] tortured… That way, the police prevent their family and lawyers from seeing them until they could coerce, through torture or other means, confessions from them.”The longer history of police torture in Chicago connects blue lights, which reside on a seemingly harmless side of the continuum of force, to the opposite end, where torture resides. Both technologies betray a societal faith in policing that excuses and extends force beyond its legal domain.

The implications for scholars interested in race and policing should be clear. We should abandon any uncritical faith in policing. It is due time that the glare of the blue light be redirected at law enforcement. Strapping police officers with body cameras is a start. But it will not solve the problem of police violence, since cultural ideas about who is a “criminal” always shape encounters and infiltrate the analysis of evidence.

What I am suggesting is that by linking itself to a broader history of protest against police violence, the cell phone camera that a protester points at a police brigade in the midst of occupying a burning city might be seen as one attempt to peel back the secrets that seldom gain public recognition. Such revelatory acts, one by one, aggregated, might just expose the cruelty a society allows itself.

Shouldn’t Black Lives Matter All The Time?

by Elliott Currie

The country, indeed much of the world, has been transfixed by the recent spate of police killings of Black men in the U.S. The names of those men—including Michael Brown, Walter Scott, and Freddie Gray—and the places where they died—Ferguson, North Charleston, and Baltimore, respectively—will surely resonate in our minds for a very long time. That’s as it should be, but I’ve found myself increasingly troubled by the way we talk about these events. More precisely, by what we leave out when we talk about them.

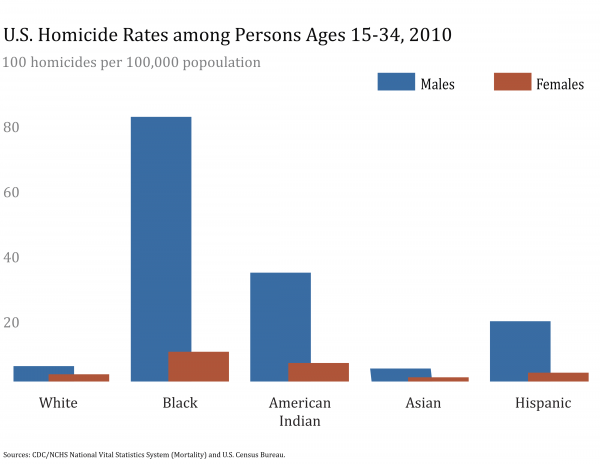

The outrage over these killings is certainly justified, as is the sense that they reveal something both morally disturbing and deeply illuminating about the nature of race relations and of policing in the United States. But what troubles me is that we seem far less outraged by the much larger number of Black men who die quite predictably in America’s cities year in and year out, mostly at the hands of people very much like them. Their deaths may or may not reach the media. But they are reflections of the larger social catastrophe of which police killings are only one part. And their lives and deaths should matter, too.We can catch a glimpse of that catastrophe in the cold figures on race and homicide deaths supplied by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overall, in 2013, the Black homicide death rate in the United States was almost exactly seven times the rate for non-Hispanic Whites. If Black Americans had enjoyed the same homicide death rate as Whites, more than 6,900 of the roughly 8,000 Black homicide victims that year would have lived. Put the other way around, if non-Hispanic Whites suffered the same risk of homicide death as Blacks, there would have been about 35,000 White homicide victims instead of the roughly 5,000 who actually died in 2013.

For the group of Americans most at risk—young Black men—these differences are, of course, much starker. Between the ages of 15 and 29, Black men have sixteen times the homicide death rate of their White counterparts. I think I can guarantee you that if 13,000 young White men had lost their lives to violence in 2013 (instead of 836), the outcry would have been deafening, and the demand for real solutions vocal and earnest.

It doesn’t diminish the tragedy of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson to point out that over 100 young Black men died of homicide in the state of Missouri in 2013. But it does suggest that our concern about—even knowledge of—the loss of young African-American lives is troublingly selective. I doubt that, at least outside of Missouri, most of us could give a name to any of those young victims. But they are no less victims, and their deaths are no less a reflection of the devastating impact of the structural conditions that shape Black lives.

Why do the deaths of Black men at the hands of police stir a usually sleepy American conscience, while the far more common community violence mostly flies beneath the radar? Partly, I’m sure, because there is a special sting to killing when it’s done by agents of the state: it symbolizes, in a particularly inescapable way, the reality of official complicity in maintaining the whole system of racial injustice. Killings by police are an especially harsh reminder of where things really stand in an ostensibly post-racial America. But I think there’s more to it than that.I suspect that it outrages Americans less when Black youth kill other Black youth because it is hard for us to grasp the idea that this kind of killing, too, has social roots—that it is part and parcel of the same system that gives us the callous brutality of police in Baltimore and North Charleston. When the hand that holds the gun is a White police officer’s, the connection between the shooting and generations of structural racism is immediate and direct. When the hand belongs to a 19-year-old Black kid, the connection is complex and indirect. But our widespread failure to make that more demanding connection represents a failure of the moral as well as the sociological imagination. In a deeply individualistic culture, we “see” the social in killings by police in a way that eludes us when youth kill each other.

Let me be absolutely clear: I’m not suggesting that we should care less about the killings by police than we do, but that we should care about endemic youth violence more. And I’m also suggesting that we are unlikely to make much progress against either kind of killing until we clearly acknowledge that both result from the same stubbornly entrenched social forces that have made all too many Black lives seem expendable.

Toward Harm Reduction Policing

by Katherine Beckett

Across the country, urban governments face significant pressure to reduce outdoor drug market activity and visible homelessness. At the same time, critics increasingly urge police departments to avoid the heavy-handed and often racially charged tactics associated with “broken windows” policing, stop-and-frisk, and the failed drug war. Identifying a productive way forward in the context of these contradictory pressures is no easy task. But in Seattle, a new program shows how police discretion and resources can be mobilized to serve humanitarian ends and reduce reliance on our bloated criminal justice system.

Like most urban police agencies, the Seattle Police Department (SPD) relied heavily on racially disparate drug war tactics in recent decades. It also created and employed controversial new legal tools in an effort to restrict the spatial mobility of those deemed “disorderly.” Yet these aggressive enforcement tactics did not eradicate the social ills associated with homelessness or open-air drug and sex markets.

The persistence of urban “disorder” triggered significant community pressure to do something to make the rapidly gentrifying and tourist-rich downtown area feel more hospitable to workers, residents, and visitors. At the same time, the racially disparate impact of the SPD’s drug enforcement practices was the subject of lengthy, complex and time-consuming litigation that exhausted all of those involved. By the late 2000s, no one was satisfied with the status quo, including the SPD itself. As Sergeant Sean Whitcomb, spokesman for the department, put it, “officers are frustrated arresting the same people over and over again. We know it’s not working.” Others agreed, including Racial Disparity Project staff who led the litigation.

Eventually, key leaders from affected institutions came together to identify a better way to address the problems associated with homelessness and outdoor drug market activity. The result—the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program—was launched in 2011. LEAD involves an unusually broad coalition of organizations including the Racial Disparity Project, the ACLU of Washington, the Department of Corrections, the SPD, the King County Sheriff, neighborhood organizations, and city and state prosecutors.

Under LEAD, eligible low-level drug and prostitution offenders are no longer subject to prosecution and incarceration, but are instead diverted to community-based treatment and support services. By diverting low-level drug and sex offenders into intensive, community-based social services that are guided by harm reduction principles, LEAD seeks to reduce the neighborhood and individual-level harm associated with Seattle’s drug and sex markets. The incorporation of harm reduction principles means that client participation is entirely voluntary, and has been key to ensuring that LEAD does not represent yet another “diversion” program with net-widening effects. A recent evaluation indicates that LEAD significantly reduces recidivism—by up to 60%—and thus represents a far more productive response to the human suffering that accompanies poverty and addiction than conventional drug war tactics.The success of LEAD in Seattle does not mean that implementing LEAD-like programs and ditching the drug war is a simple matter. For example, securing the support and involvement of line officers in LEAD has proven challenging. LEAD case managers continue to wrestle with structural problems such as the lack of appropriate treatment options and affordable housing for people with addiction histories and criminal records. And at the time of this writing, the SPD had recently worked with federal authorities to conduct a massive sweep of the downtown area, arresting over a hundred low level dealers, many of whom are homeless and addicted.

Still, the slow but steady expansion of LEAD across the city, the increase in officer involvement in LEAD, and the steady uptick in clients served by LEAD—and diverted from the courts and jails—are encouraging. The unprecedented expansion of the criminal justice system in the United States has left critics of mass incarceration wondering how we can reduce our nation’s reliance on police, jails, and prisons while more effectively addressing complex social problems such as poverty, mental illness, and addiction. LEAD suggests one plausible (if somewhat ironic) answer: use expanded police resources to divert people away from the criminal justice system, and use private and public monies to provide housing and desperately needed services, even when clients are unable to achieve abstinence. The future of our most vulnerable urban residents may depend on it.