Police Officers Need Liability Insurance

A series of high-profile shootings have sparked a national debate regarding the deadly use of force by police officers and their relationships with the citizens in the communities where they serve. Police officers have the legal authority to use physical and deadly force, when warranted, to fulfill their official responsibilities and duties as law enforcement agents. However, researchers, such as Nix, Pickett, Wolfe and Campbell, have indicated that tension and distrust between many in minority communities and police officers persist. There is a problem with trust between the public and police officers regarding the determination of the reasonable use of force practices by police officers. According to Katz, broad cross-sections of the public have lost trust in local law enforcement agencies. This lack of trust is due to their perception of biased investigations of deadly-force incidents such as the Eric Garner and Michael Brown cases that did not result in criminal charges by the grand jury.

A survey by the Bureau of Justice Statistics on Police-Public Contact Survey showed that on average, 273 out of 100,000 blacks experienced police force every week compared to 76 whites 100,000. Further, 14 percent of blacks and 6.9 percent of whites experienced force during street stops. According to White and colleagues, these circumstances continue to break the police-citizen relationship. Since police depend on public cooperation and support to function efficiently, i.e., serving as witnesses, helping with investigations and reporting a crime, public perceptions of police officers as illegitimate could prove detrimental to divisions and their attempts towards public safety and crime control. Despite its important purpose, the application of force emerges as one of the most controversial elements of police work. According to scholars, when citizens believe that police officers are applying excessive or lethal force, it can rapidly erode the legitimacy of police and can lead to far-reaching implications. Reactions such as civil disorder, loss of life, civil judgments, and criminal prosecution are all possibilities. The controversial circumstances surrounding the police application of force alongside the associated concerns of legitimacy have emerged again in the last few years.

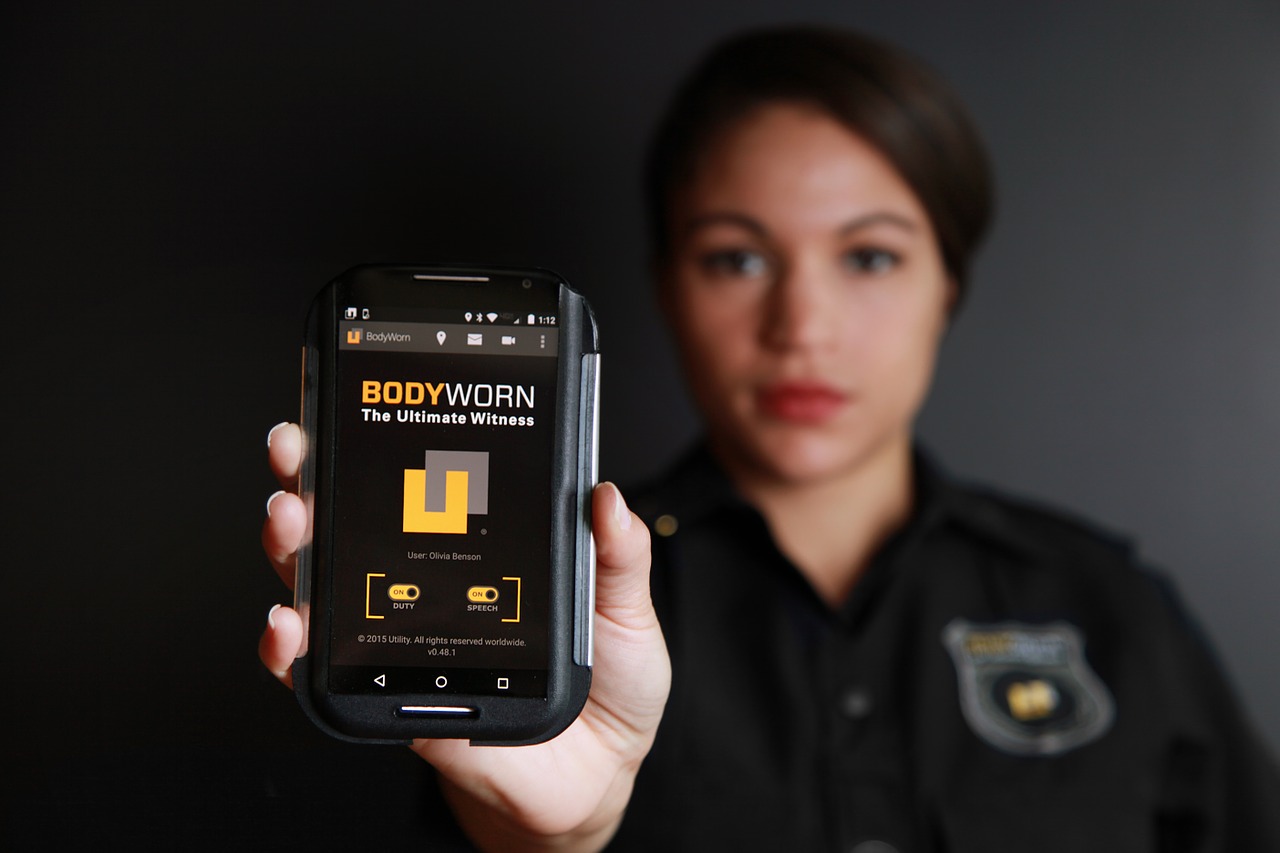

The Limits of Body Worn Cameras

A popular policy for reducing the use of police force is the body worn camera. In theory, if police know that their actions are subject to review by the public, they will exert more caution. Recently, researchers have begun to investigate the efficacy of the body worn camera (BWC). Several studies regarding the use of BWC’s have been conducted to address police-civilian interactions and police accountability concerns. Hedberg, Katz, and Choate investigated data from two settings in Phoenix, Arizona (one as a control and the other who were assigned BWCs) to approximate two measures of BWC’s effectiveness in decreasing problematic citizen-police encounters. The researchers approximated the impact of the officers who were allocated a body-worn camera, yet were not necessarily utilizing it, using data derived from more than 44,000 events. Decreasing resistance and complaints were linked to the impact of BWCs if they were utilized with total compliance.

The existence of a BWC has generated a decrease in complaints of around 62 percent, indicating that when BWCs are used as recommended, many complaints against police officers will cease. Police officers, alongside those they encounter, could behave differently if a BWC is available, regardless of whether it is active. However, the investigators also discovered low rates of compliance in BWC activation with the gadgets, being activated in a paltry 32 percent of events, mostly involving violent offenses and domestic violence. Had officers adhered to department policy, the investigators estimate that complaints may have decreased by 96 percent.

Additional studies investigated the effect of BWCs with research designs that did not use randomized controlled trials (RCTs). For example, research in the Mesa, Arizona law enforcement division reported fewer civilian complaints as well as the application of lethal force events following the implementation of BWCs as compared to non-BWC police officers. Furthermore, the study in Phoenix, Arizona found reductions in civilian complaints about police officers wearing BWCs and an effect on domestic violence case processing following the implementation of BWC.

Police Liability Insurance

Having police officers purchase and maintain liability insurance would serve several purposes; to address police misconduct, increased civil litigation action, and improve trust between minority communities and law enforcement. According to Ferdick, evidence exists to posit that fear arising out of libelous claims against law enforcement officers might affect them. However, what was unclear is whether fear triggered by municipal lawsuits affect how they work. A troubling pattern for law enforcement administrators and agencies is the rise in litigation, along with increments in monetary awards in police misconduct litigations (Chiarlitti, 2016). A report released by the Comptroller of the City of New York in 2013 offers details concerning the increase in civil claims against law enforcement officers. In the fiscal year 2012, 5,601 lawsuits were filed against New York law enforcement officers, translating to a 22 percent rise, compared to 4584 lawsuits filed in the fiscal year 2011.

According to Otu, civil liability action against law enforcement officers is a remedy option granted to an injured party pursuant to 42 U.S.C § 1983. Lawsuits under the 1983 statute are often filed due to alleged excessive force, failure to intervene, malicious prosecution, and false arrest against police officers. A 2014 study by Schwartz on police indemnification found that law enforcement officers are often indemnified. In the period of the study, governments paid about 99.98 percent of the money that plaintiffs recovered in legal suits over alleged civil rights violations by police officers. Additionally, the study found that police officers did not satisfy punitive damage awards filed against them and nearly did not contribute anything to judgments or settlements – even in a case where indemnification was barred by policy or law and even where police officers were prosecuted, sacked, or disciplined for their behavior.

Indeed, given considerable indemnification of municipal and individual liability for constitutional torts that police officers commit, an insight into how insurers control police risks are important to any persuasive theory of civil deterrence of police misbehavior. Notably, insurers change uncertain, vague liability exposures into well-ingrained policies that are supported by differentiated premiums as well as coverage denial threats. That constitutes a significant portion of how civil liability serves as a deterrence to misconduct within insured jurisdictions.

Requiring personal civil liability insurance for police officers can provide several benefits that include lawsuit deterrence and improving law enforcement accountability. Insurance theory cautions the use of moral hazards—the insurance propensity of reducing the incentive of the insured to avert harm. For instance, regarding the purchase of police liability policies, activists allege that law enforcement officers do not have a shield that holds them back from egregious conduct reports Rappaport. Implicit in such thinking is the assumption that tort liability threats would eliminate indemnification via insurance and serve as a deterrent to police misbehavior by making police officers internalize the costs of harm perpetrated by them. Liability insurance neutralizes or dilutes deterrence by shifting the liability risks from municipalities to the insurers. Given the forms of grave damages police misbehavior can inflict, the likelihood of under-deterrence presents serious issues.

Moral hazards are just the beginning. Insurers tend to develop financial incentives through risk management practices when the risk of liability is high. Through the reduction of risk, insurers reduce their payouts based on liability policies, thus increasing profits. An efficient mechanism for preventing losses can also assist insurers to compete for business through the provision of lower premiums. Simply put, insurers writing police liability insurance might rake in profits by decreasing police misconduct. Their contractual relations with municipalities provide them with the influence and means required to initiate such insured move-to-control municipalities. Indeed, the insurers might be in a better position than the local governments to initiate police conduct reforms. Unlike government regulators, insurers might have superior data that traverses many law enforcement agencies. If insurers employ the loss-prevention mechanisms at their disposal, they can reintroduce or increase the deterrent effects of constitutional tort laws. Given that, this policy recommendation seeks to offer evidence-based findings that policymakers could apply in reforming not only law enforcement practices but the criminal justice structure as well.

Expanding the scope beyond police liability insurance, the same principle can be applied to business liability insurance. Insurers have a vested interest in mitigating risks associated with various business operations, ranging from product liability to professional negligence. By implementing stringent risk management practices, insurers can minimize the occurrence of costly claims, thereby bolstering their bottom line. This dynamic creates an opportunity for insurers to exert influence on businesses, nudging them towards safer practices and compliance with regulations. Moreover, businesses seeking coverage are incentivized to adopt risk-reducing measures to qualify for lower premiums, fostering a culture of proactive risk management. In this context, reviewed business liability insurance companies play a pivotal role as facilitators of risk mitigation strategies, driving positive changes in corporate behavior while simultaneously enhancing their own profitability. By leveraging their expertise and resources, insurers can catalyze improvements in safety standards and legal compliance across industries, ultimately contributing to a more resilient and responsible business landscape.

Currently, police officers have a very problematic relationship with the citizens they monitor and the municipalities that employ them. Police officers may use excessive force, but they aren’t compensating plaintiffs. The proposed policy shifts risk back to law enforcement officer and insurance firms, who are in a position to collect data on police use of force and can provide guidance to municipalities on what is a tolerable risk.

References

Chiarlitti, A. P., (2016). Civil liability and the response of police officers: The effect of lawsuits on police discretionary actions. Education Doctoral.

Ferdik, F. V. (2013, August). Perception is Reality: A Qualitative Approach to Understanding Police Officer Views on Civil Liability. International Police Executive Symposium, 49th ser., 1-25.

Hedberg, E. C., Katz, C. M., & Choate, D. E. (2016). Body-worn cameras and citizen interactions with police officers: Estimating plausible effects given varying compliance levels. Justice Quarterly.

Katz, W. (2014). Enhancing accountability and trust with independent investigations of lethal police force. Harvard Law Review Forum, 1(28), 235-245.

Nix, J., Pickett, J.T., Wolfe, S. E., & Campbell, B.A. (2017). Demeanor, Race, and Police Perceptions of Procedural Justice: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments. Justice Quarterly, 34(7), 1154-1183.

Otu, N. (2006). The police service and liability insurance: Responsible policing. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 8(4), 294-315.

Rappaport, J., (July 8, 2016) An Insurance-Based Typology of Police Misconduct. University of Chicago Legal Forum 369; U of Chicago, Public Law Working Paper No. 585; University of Chicago Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Research Paper No. 763.

Schwartz, J. C., (2014). Police Indemnification. New York University Law Review Vol. 89:885 PP 885-1005.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). (2013). The National Crime Statistics Exchange (NCS-X).

Rarkimm Fields is a business faculty member in the College of Business at Western Governors University where he assists first generation and working adults earn undergraduate degrees in business. Rarkimm’s research interests include policing, social justice & sustainability studies, and public policy initiatives.

Comments 2

Okpo Eto

June 12, 2020Rarkimm,

Your piece is interesting and thought provoking, but you should have made a clear notification/citation that Professor Otu was the first person EVER to introduced the concept of Police/liability insurance:

Otu, N. (2006) The Police Service and Liability Insurance----------------------------------

James Hinlen

August 24, 2020The exhibition of the racism, which I noticed in the recent rallies against and for the police department have entirely startled me. Both sides were very intense, showing their hate for one other. America is way much better than this. There are a number of cases of police brutality in America I have talked about them in my essays, and you can get more info on this matter at this https://eduzaurus.com/free-essay-samples/police-brutality/ source because it guided me about how I can write an incredible essay about this topic.