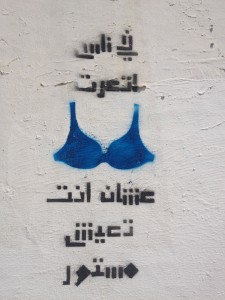

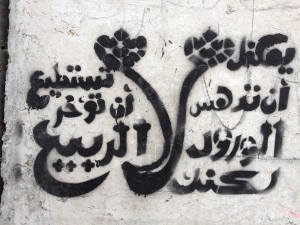

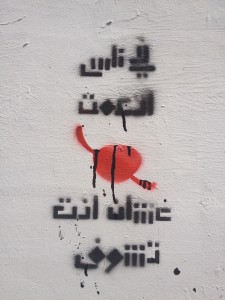

Some people have been imprisoned so you can live freely. (Art by Bahia Shebab)

Arab Winter

On December 17, 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor, set himself on fire to protest the humiliating treatment he received at the hands of the police.

This sparked the Arab Spring, starting in Tunisia and spreading rapidly throughout the Middle East and North Africa. American diplomatic cables released through Wikileaks helped to fan the flames of the uprising with frank reports of the rapaciousness of dictators in the region, including Tunisia’s Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Concerns that had been whispered in private were now in full public view, and fueled the spirit of the Arab Spring in many countries. By September 2012, dictators had been deposed in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. But the revolts that spread to other countries were crushed, coopted, or had begun to die out. In Syria, a brutal civil war continues. Spring had turned to winter.

These essays examine different aspects of the Arab Spring revolts. Charles Kurzman begins and Sarah Leah Whitson ends with rather bleak overview assessments. Kurzman’s story is of how strongmen in the region who were not among the four deposed dictators have survived and tightened their grip on power. Although Egyptians and Tunisians overthrew their dictators, Whitson is pessimistic about long-term social and political change due to the persistent lack of public support for freedom of speech. The other authors offer views of the struggles within individual countries. Dalia F. Fahmy looks at the status of women in post-Mubarak Egypt. Women were in the vanguard at the beginning of the Arab Spring, but now find themselves not only marginalized but, with the new constitution, relegated to second-class legal status. Justin Gengler examines the splintering of Shi‘a opposition in Bahrain after the Sunni royal regime brutally shut down their protests. Libya appears to be one of the most chaotic states in the region with a weak central government and warring militias. But Ryan Calder, surprisingly, paints a cautiously optimistic picture of the country’s future: the government has strong diplomatic relations, and is managing to slowly build social and political institutions. Perhaps most importantly, unlike the public spirit of despair conveyed in the other essays, Calder finds that Libyans are rather optimistic about their future.

- Winter Without Spring, by Charles Kurzman

- Egyptian Women Betrayed, by Dalia F. Fahmy

- Resisting Revolution, by Justin Gengler

- Libya’s Cautious Optimism, by Ryan Calder

- Restricting Speech Restricts Arab Freedom, by Sarah Leah Whitson

Winter Without Spring

by Charles Kurzman

From Oman in the east to Morocco in the west, most rulers of the Middle East managed to survive the uprisings of 2011. As fears of mass protest have subsided, these autocrats are reasserting control, imposing an “Arab Winter” on countries that did not experience a full-fledged “Arab Spring.”

In spite of these promises, revolts deepened in Syria and Yemen. Elsewhere—along with heightened repression and expanded state subsidies—these promises apparently took the edge off protest movements. Algeria ended the state of emergency maintained since 1992, when the military canceled the only free elections in the country’s history. Morocco and Oman revised their constitutions, and in Morocco a moderate Islamist opposition party won parliamentary elections and peacefully transitioned to a new government.

As popular pressure receded, plans for comprehensive democratization were withdrawn. Jordan’s monarchy manipulated a new electoral law to ensure its control over parliament, while Morocco’s king introduced a new constitution that maintains his control over all “strategic” affairs. Before elections in Algeria, the government passed a restrictive law on associations designed to hamper the opposition.

Rulers in other Arab countries refused to grant even minimal reforms, gambling that they could get by with minor concessions, combined with harsh repression of incipient protest. Muammar Qaddafi offered US$400 to each Libyan family and encouraged them to go after the “greasy rats” who were demonstrating against the regime. In Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah promised billions of dollars in new government expenditures, but no shift in policy. And President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan vowed not to run for reelection—in 2015. While Qaddafi’s gamble failed, other hardliners have managed to ride out the period of unrest.

Without meaningful checks on their power, rulers have stepped up harassment of activists. A particular target is online activism, which Arab governments view as almost magically disruptive. Bloggers, Tweeters, Facebook organizers and other digital activists have been threatened and detained in one country after another. In January 2012, Algeria extended repressive press regulations from print to electronic media. Oman arrested more than a dozen online activists in a sweep last spring and convicted them of lèse majesté, insulting the king, for complaining about the limited scope of reform in the country. In September, Jordan passed a law imposing potentially dire requirements on “electronic publications.” These measures are not as harsh as the widespread and brutal repression of the recent past, but they have been effective in containing the wave of uprisings.

The stalwarts of stability now have renewed confidence in their positions and increasing derision for democratization and for the Arab Spring movements. Algerian Prime Minister Ahmed Ouyahia told a crowd of supporters as he campaigned for reelection last year that uprisings in Tunisia and elsewhere “are the work of Zionism and NATO,” generating a “spiral of chaos” that resulted in “the destruction of Libya, the partition of Sudan, and the weakening of Egypt.” A fair number of Algerians apparently agreed—in a 2012 Gallup poll, as many respondents attributed the Arab Spring to “foreign influences” as to a “true desire for change.”

While the mass mobilizations of the Arab Spring ushered in uncertainty, frustration, and disillusionment across the region, they have also generated a sense of political vitality in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen, where the people toppled dictators. But in countries that did not have an Arab Spring, there is even more disillusionment and cynicism as dictators have strengthened their grip on power.

Egyptian Women Betrayed

by Dalia F. Fahmy

On January 18, 2011, 24-year-old Asma Mahfouz posted a video on YouTube calling on Egyptians to take to Liberation Square on January 25 to reclaim their honor and dignity. Mahfouz’s video has been credited with sparking the Egyptian uprising and ending the 30-year reign of President Hosni Mubarak. The simple chant of “One Hand”—that all Egyptians should unite for a democratic Egypt—was to usher in a new era for women. However, the 17-day uprising has led to two years of contentious politics and has marginalized the very group instrumental for its initial success—women.

Eventually women were driven from the public square they were so integral in establishing during the revolution and post-revolutionary politics have pushed them further out of the political arena. Their marginalization from negotiating the political and social direction of Egypt began during the early moments of the transitional period after Mubarak’s overthrow. The Supreme Council of Armed Forces, the interim, post-revolution authority, excluded women from the negotiating the transition by not including any women on the committee that drafted Egypt’s transitional constitutional declaration. The military council also dissolved the National Council of Women, a body meant to strengthen the position of women in the public.

The military council also cancelled the Mubarak-era electoral quota that had guaranteed 64 out 444 parliamentary seats for women. Given that the first newly elected parliament would designate a Constitutional Assembly to draft the new Egyptian Constitution, the absence of female parliamentarians meant they would have no voice in the drafting process and no opportunity to influence key legislation for the future of Egypt. Ultimately, due to the underrepresentation of women (6 out of 100 members), this Constitutional Assembly was dissolved by the Supreme Administrative Court.

The second Constitutional Assembly was intended to be more representative, yet included only seven women, with none explicitly working on women’s rights. To prevent the Assembly from being dissolved again, newly elected President Mohammed Morsi, issued a declaration barring the judiciary from dissolving the Assembly, thus cementing the underrepresentation of women in the drafting of the new constitution.

Morsi, who was the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood, a previously banned Islamist group that once supported banning women from the seat of the presidency, vowed to defend women’s rights if elected. However, in the recently approved constitution, women’s rights are not fully protected and are defined by traditional family roles. For instance, Article 10, while it allows for free maternal and child health services, also states the government will “enable the reconciliation between the duties of a woman toward her family and her work.” Further, Article 11 allocates to the state the power to preserve “morality” and to monitor the media in this regard. The article further stipulates that one of the roles of the media is to “uphold public morality” and to foster the “true nature of the Egyptian family.”

These articles designate women’s primary roles in relation to the traditional family, ultimately defining women’s duties both in public and private. If a woman’s public life infringes on her private family duties, she can be held legally accountable. This legislation is likely to lead to increased regulation and subjugation of women, and in many ways unequal citizenship, with insufficient protections from discrimination under the law. Furthermore, the new constitution does not delineate an electoral system that ensures the effective participation of women or that women will be represented within different elected assemblies.

Egyptian women, like Asma Mahfouz, came to symbolize a vision for Egypt that was based on democratic principles, participation, and social and political equality. In their struggle to bring down the Mubarak regime, Egyptian women found themselves fighting not only for the future of their country but also for their personal liberty. Today women in Egypt find themselves sidelined and still struggling to be heard.

Resisting Revolution

by Justin Gengler

On February 14, 2011, thousands of protesters descended on the Pearl Roundabout, a sprawling intersection featuring a 300-foot-tall sculptural homage to the pearl, Bahrain’s unofficial national symbol and the basis of its pre-oil economy. The government responded immediately with brutal violence. For one bloody, chaotic month, the roundabout would serve as headquarters for debilitating mass protests in demand of the basic social and political reforms pledged but ultimately abandoned by King Hamad bin ‘Isa Al Khalifa following his accession in 1999. That the Arab Spring arrived in Bahrain on February 14 was no coincidence. The date marked nine years since the unilateral promulgation of the country’s 2002 constitution, a charter that came to symbolize for regime opponents—in particular the country’s long-disenfranchised Shi‘a majority—the false promise of political reform.

Even as King Hamad pledged reform in 2002, the country’s voting districts were redrawn to dilute Shi‘a representation in the elected but toothless parliament. Shi‘a were also disproportionately excluded from powerful government ministries and entirely disqualified from police and military service. Selective naturalization of Arab and non-Arab Sunnis has dramatically increased their numbers relative to Shi‘a. Finally, to dissuade ordinary Sunnis from acting on their own considerable political grievances, the state propagates anti-Shi‘a sentiment and demonizes the opposition as an Iranian-backed fifth column.

Initially led by a broad coalition of activists, Bahrain’s “Pearl Revolution” was soon buoyed by the organizational capacity of established Shi‘a and secular groups. The Shi‘a political bloc al-Wifaq threw its considerable weight behind the protest movement when its members resigned from parliament over the deaths of several protesters. To help check the momentum of the uprising, an alliance of mainly Sunni loyalist groups orchestrated their own mass counter-mobilization, sparking sectarian clashes and threatening open Sunni-Shi‘a conflict.

By March 12, amid rapidly disintegrating law and order, government killings, and torture, the king’s son, Crown Prince Salman, was deputized to lead a government-opposition dialogue to negotiate an end to the crisis. He was authorized to discuss even the thorniest of political issues, including the possibility of a government that “reflects the will of the people.” But al-Wifaq conditioned its participation on the state’s agreement to an elected assembly empowered to revise the 2002 constitution. Several more radical factions rejected the idea of talks altogether, demanding an end to the Al Khalifa monarchy.

Faced with faltering negotiations and pressure from hardline ruling family members, King Hamad abandoned the initiative— scheduled to last six weeks—after two days. Instead, several thousand ground troops from neighboring Gulf states arrived in armored vehicles via Saudi Arabia, strengthening the Bahraini government’s resolve in the face of mounting popular and diplomatic pressure. Martial law was declared the next day, foretelling a violent end to mass protests, as well as the decisive marginalization of moderates within both the opposition and ruling family.

The same issues that precluded peaceful resolution of the crisis in 2011 have crystallized in the two years since. The crown prince’s embarrassing failure to broker a deal with opposition leaders sidelined him within the ruling family. Power and influence have shifted markedly toward more conservative figures, including the king’s uncle and long-time prime minister, who has gained strong support among (mainly Sunni) advocates of an even harsher crackdown on protesters.

Meanwhile, cracks in the opposition continue to widen. The movement today is split broadly into two groups: formal opposition societies, including al-Wifaq, which continue to hold out hope for a negotiated settlement; and a youth-oriented street movement more willing to resort to destructive and violent means of resistance. As Bahrain’s youthful activists continue to move further outside the sphere of the mainstream opposition, so too does the hope for a political solution fade. Increasing violence gives security-minded royals and citizens justification to escalate repressive measures, while al-Wifaq appears an ever more unreliable partner in dialogue, as it cannot claim to represent—much less control—the Shi‘a street.

On March 18, 2011, following a deadly nighttime raid to clear the Pearl Roundabout of demonstrators, government bulldozers razed the monument. Coins bearing its image were removed from circulation. The intersection, which has yet to reopen, was renamed Al-Faruq Junction, after the very military operation by which it was, in the government’s words, “cleansed.” Rather than address underlying sources of political discontent, then, the ruling family has sought instead to erase the very memory of the uprising. Still, two years on, protests continue, with neither societal reconciliation nor a political resolution in sight.

Libya’s Cautious Optimism

by Ryan Calder

By all accounts, Libya seems to be in chaos. Kalashnikov-toting militias run entire cities. An American ambassador was assassinated in Benghazi last September. Libyan weaponry and militants are implicated in the January attack on an Algerian gas facility that left 48 foreign workers dead. Has Libya’s Arab Spring failed? While on the surface it may seem so, there is reason for cautious optimism.

Qaddafi also had no defense ministry: the armed forces reported directly to him. He kept his army small and effete, fearing a coup d’état of the sort that brought him to power in 1969. NATO bombing destroyed most of the Libyan air force in 2011, which helped anti-Qaddafi forces win the war but made it harder for them to maintain post-war security. Today, Libya’s most pressing security problem is independent militias. Many of the militias that fought Qaddafi refuse to disarm, believing weapons will guarantee them autonomy and a stake in the new Libya.

Clashes between powerful militias from Misrata and Zintan, two western cities that suffered greatly during the uprising, have been bloody. Meanwhile, the Libyan army is so weak it has ceded control to the militias in many areas. And efforts to turn militiamen into police officers have had limited success. Many still associate the police with Qaddafi’s rule.

Meanwhile, in Libya’s south—a vast desert region dotted with oasis towns—the weak central government faces different challenges. Violence between ethnic Tabu who opposed Qaddafi, and Arabs who enjoyed Qaddafi’s support, claimed hundreds of lives in 2012. Smugglers move weapons and drugs across the porous borders with Chad, Niger, Sudan, and Algeria. Arms spilling over from the Libyan civil war even helped create the current conflict in Mali.

Despite these challenges, there are reasons to remain hopeful. Predictions that Libya would splinter along tribal lines or lurch toward extremism have proved false. National elections in July 2012 were free and fair. The 200-person legislature includes 33 women—not many, but the same proportion as the 2012 U.S. Senate. Libya looks set to write a new constitution in 2013. And the question of Islam in politics has aroused less discord than in Tunisia or Egypt because there is general consensus that Islam and sharia, or Islamic law, should play a significant but moderate and circumscribed role.

Quality of life and economic indicators are also gradually improving. By 2012, Libya’s gross domestic product (GDP) had returned to the 2010 level despite the war’s devastation; the Economist Intelligence Unit predicts real GDP growth of 9.6 percent a year between 2013 and 2017. Rapid inflation during and after the war reversed course in autumn 2012. Basic services such as water, electricity, and garbage collection are resuming in areas where the state controls security. Oil production is already at pre-war levels, although the development of non-oil industries—a perpetual headache for oil-dependent economies—continues to be a challenge.

Despite domestic disarray, the Libyan state has developed stable external relations, in stark contrast to Qaddafi’s history of military adventurism and largesse to fellow dictators. Relations with countries slow to recognize the opposition, including Russia and China, have re-normalized. Ties with neighboring Tunisia and Egypt are good.

Foreign powers’ support for institution-building will prove critical to Libya’s long-term stability. Among Libyans, the United States, Britain, and France still enjoy goodwill for having fought Qaddafi during the 2011 civil war. These governments have an opportunity that eludes them in much of the Arab world: a chance to build relations not stymied by distrust or major ideological differences. Yet foreign powers must scrupulously avoid political meddling. The Qatari government, once adored by anti-Qaddafi Libyans during the war for sending them arms, jets, and special forces, has since gotten harsh criticism from high-ranking Libyan politicians for supporting Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood chapter.

We may well see reasons for hope in 2013, especially if the Libyan state can bring the militias to heel. Most Libyans have not given up on the 2011 revolution and still appreciate their hard-won freedoms—a fact lost in news reports of domestic chaos. In the words of Libyan-American poet Khaled Mattawa: “Somewhere, an earthly sun is shining on us, with us, again. There is air in the air again.”

Restricting Speech Restricts Arab Freedom

by Sarah Leah Whitson

The sight of hundreds of thousands of Arabs marching on the streets of a number of Arab countries, demanding their dignity and rights, will remain among the iconic images of the twenty-first century. The willingness of so many citizens to take such tremendous risks to their own lives, with thousands dying for their freedom, stunned a world long accustomed to the image of the resigned, subordinate, cynical Arab masses.

Egypt offers the best example of this disconnect. The newly elected Islamist leadership has expressed its commitment to ending police impunity, unfair trials, and arbitrary detention. These were hallmarks of Hosni Mubarak’s nearly 30-year rule under its notorious Emergency Law, which allowed for indefinite detention without charge and trials by special security courts that provided few due process protections. Muslim Brotherhood members for decades found themselves enduring brutal arrests, torture, and imprisonment for the crime of belonging to an “illegal organization.” So it is no surprise the new government allowed the Emergency Law to expire (recently the government declared a state of emergency for 30 days in parts of the country) and proposed a draft constitution with strong protections against torture and arbitrary detention. In my meetings with the Muslim Brotherhood’s senior leadership, they made clear that curbing police torture and prison abuses would be among their top commitments. In the same vein, the Muslim Brotherhood’s experience of direct abuse at the hands of the Mubarak government has led to endorsement of accountability for the killings of protesters in the lead up to the overthrow of Mubarak.

Yet on the issue of free speech the new government has relied on restrictions that the Mubarak government routinely used to muzzle government critics. A new constitution written by the Islamist-dominated constituent assembly was approved in a referendum with more than 60 percent voting in favor, though only about 30 percent of the electorate voted. The constitution includes a general commitment to protect freedom of ”thought and opinion,” but then bans “insults” to individuals and prophets. And this is no theoretical danger: President Mohamed Morsi’s government authorities over the past year have investigated or prosecuted at least 22 people for “insulting” the president or the judiciary.

In Tunisia as well, the interim governments moved to investigate the attacks on demonstrators during the uprising and to prosecute security forces implicated in numerous deaths and injuries. The draft constitution strongly affirmed protections against torture and unlawful detention as well. But on free speech, the country is tied in knots. The governments have used laws inherited from the deposed president, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, to prosecute several people for speech deemed “immoral” or “harmful to public order,” such as sculptors and bloggers, but also for “impugning the reputation of the military.”

Again and again in my decades of observation and meetings in the region, I have seen widespread support for limits on speech, not just in Egypt, but throughout the Middle East. Many citizens from a wide cross-section of society see no contradiction between the right to speak critically of government officials (or their religion) and the “right” of officials (and even institutions) to punish those who allegedly insult them. Much of the Arab public cares little for the fact that international human rights law rejects “insult” as a legitimate limit on speech, because it easily can be used to stifle critics and opponents and to restrict the vigorous public debate that is essential for government accountability. Even in countries like Morocco and Tunisia, where new constitutions broadly assert respect for free speech, the authorities continue to jail people for allegedly insulting or defaming the police or government officials.

The challenge for human rights advocates in this new era is to persuade the Arab public that there can be no freedom without broad space for political speech, however obnoxious. It’s far from certain, despite the sacrifices made for freedom during the Arab Uprisings, that the public recognizes how important this issue is to their future.