Born Amid Bullets

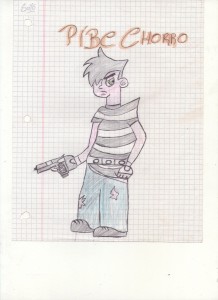

“This is a 22mm gun,” says thirteen-year-old Jonathan, pointing to one of his drawings.

Few kids his age know the names and shapes of weapons circulating in the neighborhood, but Jonathan (a pseudonym) can easily distinguish between a 45mm, 9mm, and a 22mm. When his uncle “goes out and steals around” at a nearby shantytown, Jonathan is often his lookout. At school, he spends his days listening to music on his cell phone, horsing around, and drawing; weapons are among his favorite subjects. At the end of the year, he will receive his elementary school diploma — despite the fact that his reading and writing skills are only at a fourth grade level.

Jonathan lives with his four brothers and his mother in a makeshift house with exposed brick walls and tin roofing, where he shares a small bedroom with his brothers. His house is located 20 blocks from the school in one of the most destitute areas of Ingeniero Budge, a low-income neighborhood in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area. Teresa, Jonathan’s mother, commutes an hour and and a half each way to work downtown, six days a week. She leaves the house before Jonathan wakes up for school in the morning, returning around nine o’clock at night, shortly before Jonathan goes to bed. Her salary as a maid, plus a meager sum provided by the state, is barely enough to make ends meet.

Courtesy of Javier Auyero.

her in public.

“She cooks for him, she does the laundry for him, and he’s a bum,” says a neighbor. “He says that he works as a cab driver, but he does nothing.” One day Teresa ran him out of the house with a big knife. “It’s better if he doesn’t come back,” says Jonathan.

When Jonathan’s turbulent world enters the schoolroom, his teacher is often forced to deescalate tensions between him and his peers. He has been known to threaten his classmates with the threat, “I’ll shoot at you,” or “I’ll shoot in the head,” pointing an imaginary gun at them. His uncle was recently murdered, and he believes a similar fate awaits him. One day, as his teacher ended class, he bragged out loud: “Miss, one day you’ll see me on TV. I’ll rob a bank and they will shoot at me. The police will kill me.”

Courtesy of Javier Auyero.

The daily violence that takes place in favelas, villas, barrios, and comunas — what sociologist Loïc Wacquant calls “territories of urban relegation” (urban areas characterized by multiple forms of deprivation) have been well documented. However, we know little about the ways violence is experienced by the children, adolescents, and young adults who are most affected by it, both as victims and as perpetrators. In the United States, the harmful psychological impact of chronic exposure to violence on children and adolescents is well known. Most experts agree that such exposure can have serious developmental consequences, such as anxiety, depression, impaired intellectual development, and behavioral problems. But others contend that children who constantly witness or experience different forms of interpersonal aggression become desensitized to it.

For two and a half years, I have been conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Ingeniero Budge to understand what happens when children and adolescents encounter violence as victims or witnesses. (Fernanda Berti, my collaborator works as an elementary school teacher in the neighborhood.) What we have found is that though they experience violence on a daily basis, young people remain highly sensitized to it.

Growing Up With Violence

Ingeniero Budge (pop. 170,000) sits in the southern region of metropolitan Buenos Aires, in the municipality of Lomas de Zamora. Located adjacent to the banks of the highly polluted Riachuelo River, this poverty-stricken area, like many informal settlements in Latin America, is characterized by extreme levels of infrastructural deprivation: unpaved streets, open-air sewers, random garbage collection, polluted drinking water, and poor lighting.

Courtesy of Javier Auyero.

During more than two years of fieldwork with third, fourth, and sixth graders, aged 8 to 13, shoot-outs, armed robberies, and street fights were routine topics of conversation. Hardly a week went by without one or more of the 60 children describing episodes involving violence. Trivial occasions inside the classroom, such as the mention of a relative’s birthday, often became opportunities to talk about the latest violent episode in the neighborhood. One day Marita, age nine, asked Fernanda if she knew Naria’s father. When she told her that didn’t, Marita replied, “He is in heaven. He was shot in the head.”

Eleven-year-old Estrella spoke about how her neighbor Carlitos had just turned 17. A friend came to pick him up to hang out in the neighborhood, she said. Carlitos didn’t want to go, because it was his birthday. But his friend persuaded him, and off they went. Estrella said she thinks they were armed. Carlitos was killed. After he died, his friends carried him in a procession around the block. “I went to the funeral. His eyes were still open,” said Estrella, describing how “the bullet came into his chest, and made a tiny little hole there.” The bullet went out through his back, she said. “The hole there was huge.”

Encounters with violence also pervade classroom activities. In an in-class exercise, students were asked to depict the positive and negative aspects of their neighborhood. A third-grade student portrayed his barrio as defined by “se tiran tiro” (“they shoot at each other”) and the lone presence of a police car. A year later, two fourth graders and two sixth graders depicted their neighborhood in similar terms. Most of them say they like playing soccer, and dislike “the gunshots” and “the fights.” They see themselves, many of the drawings suggest, as growing up in the crossfire.

Sixth-grade students discuss a series of short stories about “urban legends” that include ghosts, monsters, and other frightening creatures. “So…what are you all afraid of?” Fernanda asks the class. Usually reticent to speak up, the students grab the opportunity to talk about what really matters to them. The question sparks an hour-long conversation about their fears. They say that they are terrified of certain noises. Out of the seven sounds they ask the teacher to write on the blackboard, five concern crime and inter-personal violence: Steps on the roof. Rats. Shots. Screams when someone is robbed. A pistol’s trigger and barrel. Storms. One says: “When cars are stolen, they burn them and they explode.”

Shoot-outs, fights, injuries (“Does your dad have a bullet scar on the leg? My dad has two, but they have already healed”), and deaths are an ordinary presence in children’s and adolescents’ lives (“Every night, they shoot at each other… it’s hard to sleep”). Violence permeates their talk about past and future events, and is part of their everyday worlds.

“They Beat His Face To A Pulp”

“The King of Spain was deposed by Napoleon Bonaparte, and was jailed in France,” Fernanda reads out loud from the social science textbook. “Teacher, teacher,” Carlos, age nine, interrupts, “my uncle is also in jail. I think he is in for robbery.” Another student, Matu, also nine, adds: “Right around my house, there’s one guy who is a thief, but never went to jail… he has a new car.” Suddenly, a lesson on the May Revolution becomes a collective report on the latest events in the neighborhood. Ten-year-old Johnny asks: “Do you know that Savalita was killed? Seven shots.” Some dealers, he says, “wanted to steal his motorcycle.” Tatiana, age nine, corrects him: “No, it wasn’t like that. Savalita was the one who wanted the motorcycle. He tried to steal it from a drug dealer. Word, I knew him!”

Photo by Agustín Burbano de Lara V.

One day, the mother of Julio, age eight, called the school to talk to her son. Julio told the teacher, “My dad had been drinking and he beat the shit out of her. My dad is a slacker, he doesn’t have a job. My mom gives him money and he spends it on wine. On Saturday, my mom asked him to turn the music down and he slapped her in the face, and then he grabbed her hair and dragged her through the house. He also destroyed everything in the house.” When Julio’s mother came to school, she confirmed this and asked the teacher to observe Julio to make sure his dad was not beating him. She also asked her son, Julio, to take good care of his sister because she was afraid her dad will sexually abuse her.

Girls in the neighborhood are more likely than boys to endure sexual violence, reflecting larger patterns. Referring to the presence of “violines” (those who violan, or rapists), Noelia, age nine, tells the teacher that her cousin was “almost raped yesterday” a few blocks away from school, and that neighbors went to the home of the suspected rapist and “kicked their door down.” “What are ‘violins’?” Fernanda innocently asked the class. “Those who make you babies,” eight-year-old Josiana answered matter-of-factly.

Sexual assault is sometimes followed by vigilante violence. For example, Mabel explains the origins of the bullet that is lodged in the leg of her 10-year-old daughter, Melanie. “That son of a bitch wanted to rape her,” she said. “We have a big family, so we had asked a neighbor to roast some meat for us,” she said. “This is a neighbor I’ve known all my life. My brother-in-law brought home some of the food, but some was missing so I sent Melanie and my niece to pick it up.” When they got to the neighbor’s house, he was drunk and had a knife in his hand. He wanted to rape them.

“He told Melanie and my niece that if they didn’t suck his dick, he was going to kill one, and then rape and kill the other one.” Luckily, they were able to push him aside, perhaps because he was drunk, and they escaped. They ran home and told their relatives what had just happened. Mabel’s husband, brothers-in-law, brother and some other neighbors went to the threatening neighbor’s house and “beat the shit out of him (lo recagaron a palos),” she said. “They beat his face to a pulp, he was full of blood. They left him there, lying on the floor, and came back home.” After dinner, around midnight, Mabel recalled, he came to their house, and shot at Melanie. “Luckily, the bullet hit her in the leg. All the men in my house went back to his house and beat the shit out of him again.” Fortunately, Melanie was never raped.

Over the course of our fieldwork, we heard dozens of stories of the rape, or attempted rape, of girls by acquaintances or family members. In most cases, the rapists were uncles or step-fathers. The students report these stories, as do their mothers. In individual interviews, mothers articulate their fears: “I can’t let her go alone. What if they rape her? It’s frightening.” Despite this very real threat, few trust the police to address such cases. They believe they are too slow to react to sexual violence. Some say “the police always come late, to collect the body if someone was killed, or to stitch you up if you were raped.” Others say the police are complicit, and rumors of what one neighbor calls “the blowjob police,” cops who demand sexual favors from neighborhood adolescents, run rampant.

Habituating to Violence

Victor told Fernanda that a little kid was killed close to his home the day before: “They were a band of thugs (chorros), or maybe dealers (transas),” he said. Estrella interrupted, saying that she heard the shooting. Minutes before it happened, she was hanging out on the sidewalk. When the teacher urged them to be careful, Victor and Estrella replied in unison: “We are used to it.”

The recurring incidence of different types of violence makes the neighborhood a hostile, dangerous place for children and adolescents. But are they habituated to the violence that engulfs their homes, streets, and schools?

If by habituation, or desensitization, we mean that children and adolescents are less likely to become aware of incidents of violence, then our research, which shows that children talk almost compulsively about the latest shoot-out, murder, or sexual assault, proves that they are far from habituated. They expressed fears that show they are highly sensitive to the violence that envelops their neighborhood. However, if by habituation we simply mean familiarization — as in “we are used to it,” then we should take these children’s words at face value. Violence has become a normal presence in their lives.

The accumulation of what community psychologists call “stressors” wreaks havoc on children. As anthropologist Jill Korbin so aptly puts it: “Children can sustain broken bones with no lasting-effects. They cannot easily recover from broken spirits, when their bones are broken purposively out of malevolence or disregard.” Exposure to chronic community violence also contributes to the learning of aggression. For example, children and adolescents may learn things such as how to use weapons such as a knife or a gun, or their bare hands, to stop or initiate a physical attack, where and how to acquire a gun, and how to distinguish between their different calibers.

Understanding and explaining the violence that puts residents of poor urban areas in harm’s way requires objective measures like counting bodies and injuries. But we also need to understand how constant exposure to violence shapes individuals’ lives and worldviews. That means listening to those who suffer most — such as the children and adolescents who live in places like Ingeniero Budge.

Recommended Resources

Alarcón, Cristian. Cuando Me Muera Quiero Que Me Toquen Cumbia: Vidas de Pibes Chorros (Norma, 1999). A wonderfully written non-fiction narrative on daily violence in poor neighborhoods in Buenos Aires.

Friday, Jennifer. “The Psychological Impact of Violence in Under-served Communities,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved (1995), 6(4):403-409. A comprehensive review of the effects of chronic exposure to violence.

Guerra, Nancy, Rowell Huesmann, and Anja Spindler. “Community Violence Exposure, Social Cognition and Aggression Among Urban Elementary School Children,” Child Development (2003), 74(5):1561-1576. An article documenting the harmful impacts of repeated exposure to community violence on children’s schemas of perception and appreciation.

Imbusch, Peter, Michel Misse, and Fernando Carrión. “Violence Research in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Literature Review,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence (2011), 5(1):87-154. A recent, thorough review of diverse forms of violence in contemporary Latin America.

Korbin, Jill. “Children, Childhoods, and Violence,” Annual Review of Anthropology (2003), 32:431-46. A review of different types of violence to which children around the world are subjected.

Rodgers, Dennis, Jo Beall, and Ravi Kanbur (eds.). Latin American Urban Development into the 21st Century: Towards a Renewed Perspective on the City (Palgrave, 2013). A book on past, present, and future urban research agendas in Latin America.