Dorothea Lange and the Art of the Caption

Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” is one of the most reproduced photographs in the world. Like other iconic images, it has taken on a life of its own, a symbol of the Great Depression. It’s an indelible image, of course, illustrative of a collective tragedy. But symbolism was not Lange’s aim when she took the photograph in 1935 while under government contract to document agricultural poverty.

During the five years she worked on and off for the Farm Securities Administration, Lange was a melder of genres, both an art photographer and a sociological researcher. She pushed documentary photography further than social realism. She used her camera as an exploratory tool rather than as an illustrator of what she already knew. Lange did not want her photographs to be timeless insights into human universals. In later interviews she referred to herself during these years as a visual sociologist, a discoverer, a social observer.Unlike her contemporaries, Lange took extensive field notes, which evolved into a General Caption, crafted with observations, interviews, and economic data to work with a series of photographs curated to tell a story. She pioneered this method, synthesizing art and social science. “Every photograph… belongs in some place, has a place in history—can be fortified by words,” she said in a 1965 interview. “I’m just trying to find as many ways I can think of to enrich visible images so they mean more… A purist would just put not a line.” Her project was uniquely her own.

Lange was foremost an artist whose Depression work was long underappreciated in comparison to her male contemporaries. Certainly, gender played a part in this discrepancy, but she may also have been overlooked because of the way she blurred the lines between art, documentation, and research. She stepped outside of her role as artist in her engagement with her subjects. Her work during this period was not only about creating beautiful pictures, not was it about simply representing the facts. Again and again her work asks us to look closely at the poor, to really see them.

***

Lange was a portrait photographer for wealthy clients in San Francisco when the Depression hit. She was first hired as a field photographer by Berkeley economist and soon-to-be second husband Paul Taylor, who was working for the State Emergency Relief Administration to assess the situation of migrant agricultural laborers. Taylor believed that better governmental relief policies could be attained by publicly revealing the scale of the social crisis. Further, by focusing on the problem of one individual, the public could begin to understand larger societal problems.

At the time, photographs of social problems were rare, and among social scientists, only anthropologists had begun to use photographs. Sociologists feared photography was too emotionally loaded to be scientific. But Taylor believed Lange could help show what conditions were like. Taylor and Lange traveled across California, photographing and interviewing displaced migrants.

The FSA, under the Department of Agriculture, was created in order to provide relief for the rural poor, issuing low interest loans, helping improve soil conditions, and devising programs to help resettle displaced and out-of-work farmers. Like Taylor, Roy Stryker, head of the Information Division, believed that showing the public the plight of the farmer would lead to support for government aid. He hired photographers—some of the best of the era including Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, Arthur Rothstein, Russell Lee, and Marion Post Wolcott—to create a visual encyclopedia of rural poverty. When Stryker first saw the photographs Lange had done with Taylor, he was ecstatic and hired her immediately.

Many of Lange’s peers saw themselves as artists and never wavered. Walker Evans would have his subjects hold still, giving them a timeless intensity, even using trick viewfinders to lull subjects into thinking he was looking the other way. He kept a distance between himself and his subjects, and included no identifying captions or information. His aim was always his art.

Lange’s project was something quite different. She sought to get as close as she could to her subjects. She felt she had a mission not only to document poverty but also to examine the agricultural system from which it grew, using her camera, interviews, and observations. She would talk to people and ask questions. “The words that come directly from the people are the greatest… If you substitute one out of your vocabulary, it disappears before your eyes,” Lange said in a 1965 interview. She recorded the location and date, remarks made by people she met, and statistics that described their lives—what they earned, what they paid for food and rent, ages of children. “What the right words can do for some photographs is enormous.”In 1936, the FSA’s Stryker met with noted sociologist Robert Lynd, then at Columbia, about the use of the camera in social documentation. Lynd and his wife Helen were best known for the Middletown Studies, case studies of Muncie, Indiana, which looked at the impact of modernization and economic changes upon a typical American city. Lynd urged Stryker to investigate sociological questions through his photographers. Lynd suggested they ask questions like, “Where can people meet?” “What is the relationship between time and the job?” “How many people do you know?” and look at filling stations, stores, cafes, bus stations, and the streets.

Stryker knew little about the technical aspects of photography, but he cared about the ideas behind them. He pushed his photographers to think about their work in a sociological context. After meeting with Lynd, he began to develop “shooting scripts.” Lange and Stryker often saw eye-to-eye about how and what to record, so instead of using a script, Lange would outline her plans for his approval. Stryker would review her prints and send them back for captions.

Lange did not invent the General Caption. Ben Shahn, also working for the FSA, had grouped his photos of rural Ohio thematically under General Captions the summer before she had. But she perfected it, editing her photographs to give a visual correlative to the information in the caption, honing her own style of documenting to complement the narrative of her photographs. By providing details and life histories of her subjects, she connected personal experience to historical institutions. Captions both expanded the meanings of her photographs and limited them. By rooting her subject matter in specifics, her photographs resist being universalized and insist on bringing the viewer into the story.

Stryker wrote to Lange in a 1939 letter, “I think this idea of General Captions is the best [that] has come out for some time. The photographic material is enhanced no end when so much good information is available.” But despite his trumpeting of their importance, he never used Lange’s General Captions in public displays or other published materials. Lange hated what she saw as the decontextualization of her work. It wasn’t until 2008 that many of her field notes were published. Stryker controlled the images, and she was infuriated that he didn’t allow her to retain her own negatives and thus supply photographs directly to publications grouped with text as she envisioned them.***

In June 1939, Lange traveled to North Carolina to help sociologists from the Institute for Research in Social Science at the University of North Carolina explore how photography could augment other research methods. The program’s director, Howard Odum, recruited social scientists Margaret Hagood and Jarriet Herring to lead a photographic study of thirteen counties in the Appalachian Piedmont. The Institute was preparing an exhibit on “photographic portraiture as exploration in the field of research through photography.” Hagood called Lange “a pioneer in this new mode of social research.” Lange would photograph sharecroppers’ families and farms, the process of tobacco farming, and community life throughout the region.

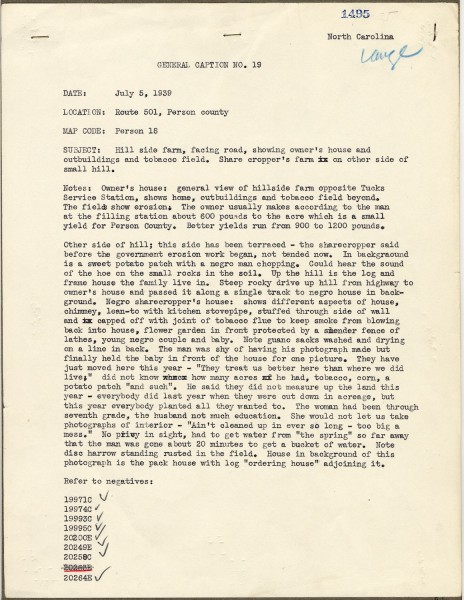

Lange’s General Caption No. 19 is from a visit to a farm in Person County, NC. She sets the scene, including relevant contextual information—land yield compared to others in the county—and sensory detail: “Could hear the sound of the hoe on the small rocks in the soil.” She gives her impressions and observations—“The man was shy of having his photograph made”—and includes direct quotations. The white landowner is only noted by his log-and-frame house and in the sharecropper’s words: “They treat us better here than where we did live.”

Lange also provides facts about the family’s education, where they get their water, how long they have lived here. But it is in her vivid details—the guano sacks drying on the line, the flower garden in front protected by a slender fence, the woman who wouldn’t let Lange photograph inside the house because, “Ain’t cleaned up in ever so long” —that Lange’s particular vision is revealed.

From hundreds of negatives, Lange chose eight to accompany this General Caption 19. The photos, four of which are shown here with their short captions, flow alongside the General Caption, with a wide view of the farm and land, then closer in on the dwellings, and closer still to the remarkable portraits of a young family and their sharecropping life.

Stryker and Lange had a productive, yet tempestuous, relationship. He was a bureaucrat who needed to protect his sense of power, and he found Lange a difficult woman of passion and exacting standards. He fired her three times, for good in 1939.

Lange and Taylor collaborated on American Exodus, a book project depicting the migrant experience. Thirty years later, art historian and photographer Beaumont Newhall called the book “a bold experiment pointing the way to a new medium, where words and pictures do not merely explain and illustrate: they reinforce on another to produce… the ‘third effect.’” This “third effect” was born and perfected in her work for the FSA.

As the Depression eased and WWII captured national attention, the rural story Lange had worked tirelessly to tell faded from public consciousness. The FSA photography project was shut down in 1942. Its archive holds more than 165,000 photographs—perhaps the best example to date of the use of photography as a tool for social research.

Much of popular understanding of the Great Depression comes from visual images. When I look at those images, my question is always: Who are those people? Dorothea Lange answered that question with her insistence on connecting the viewer to what is being viewed and her dogged pursuit of rounding out the story. Lange made a distinct contribution to social science with her hybrid method of investigation. By closing the gap between herself and her subjects and cultivating rich field notes to inform her photographs, she pushed documentary photography to a new, invigorating space. She was a mash-up visionary who refused to stay within prescribed boundaries and limited frames.