Gender in the One Percent

The disparity between the average income of a one percent household and an average household in the 99% is stark: $2,347,494 versus $76,120.

The households in the top one percent of the U.S. income distribution control enormous quantities of financial resources. They receive 24% of all household income, and the minimum amount of income needed to be in this elite group is $845,000. The disparity between the average income of a one percent household and an average household in the 99% is stark: $2,347,494 versus $76,120. Due to their extensive financial resources, people in the one percent enjoy unparalleled political, economic, and social power and influence. Many use their high incomes as a resource to influence other powerful members in the community and to shape public policies and broader social environments in their favor.

Growing inequality has renewed research interest in the one percent, and these households have also become a staple of public discourse. The Occupy Wall Street movement that followed the Great Recession reintroduced the one percent into the public dialogue, and politicians have incorporated discussion about the one percent in their campaigns. During the 2016 presidential race, Bernie Sanders frequently referenced the one percent to rally his base and to bolster support for his proposed policies aimed at reducing inequality. Similarly, Democrats entering the race for the 2020 presidential election—including Elizabeth Warren—frequently reference top income earners and propose policies that would alter income and wealth distributions.

In scholarly and public discourse, the top one percent is typically conceptualized as a joint household status which members, frequently married women and men, equally contribute to and enjoy. What is missing from this discussion is the role that gender plays in elite households. Certainly, rich women and men both enjoy substantial privileges compared to people in other households. High income can buy a safe and pleasant living environment, improve children’s educational opportunities, provide a financial buffer against medical emergencies, and can be saved to extend these benefits to future generations.

However, conceptualizing the one percent as a shared economic status masks whose income and employment (men’s or women’s) is primarily responsible for pushing a household into the one percent. Additionally, the focus on the household obscures the reality that the person who contributes more to the household’s financial status is likely to have more power inside the household and greater social influence, political power, and prestige outside the household.

In this piece, we discuss gender income dynamics in the one percent and show that white, heterosexual, married men earn most of the income in this elite group. We propose that, as a result of their disproportionate contribution to household income, men in the one percent likely exercise considerable power, both inside and outside of the household. To be clear, we are not claiming that (mostly white, heterosexual, married) women in the one percent are disenfranchised; rather, we suggest that a small group of homogenous men likely hold most of the substantive status and influence in the one percent. This phenomenon may have important social and political implications.

…we are not claiming that (mostly white, heterosexual, married) women in the one percent are disenfranchised; rather, we suggest that a small group of homogenous men likely hold most of the substantive status and influence in the one percent.

We improve understanding of the one percent in two ways. First, we provide empirical estimates of men’s and women’s income contributions to household one percent status using the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF). The SCF is ideal for this work because it includes both a nationally representative sample of households and a sample of high-income households — a group that is vastly underrepresented in most survey datasets. We also examine important spousal characteristics (e.g., high-earner status, employment rate) of high-income women and men to explore whether women who do make it to the one percent based on their own income enjoy the same family privileges as their male counterparts.

Second, we draw on information from previous research on elites to speculate about the broader implications that gendered income patterns have for inequality internal and external to households. Specifically, we highlight that breadwinning men in the one percent may have greater decision-making power in the household, and they may exercise more of the political influence that comes with being an elite. Then, drawing on research on gender differences in ideology and political campaign contributions, we postulate how women might exercise power differently than men if a greater number of them earned high incomes.

The One Percent: Who are They?

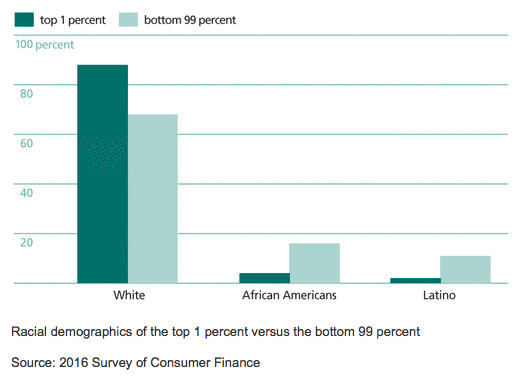

It has become clear that the one percent is unique demographically and financially. The typical household in the one percent is more likely to be a white, heterosexual, married couple compared to other households. Indeed, about 89% of households in the one percent are different-sex married couples, whereas only 55% of households in the bottom 99% are different-sex married couples. Similarly, 88% of those in the one percent identify as white, compared to 68% of those in the bottom 99% (see Figure 1). African Americans and Latinos are particularly underrepresented at the top: 4% of those in the one percent are African American, and 2% are Latino. In the rest of the income distribution, 16% identify as African American and 11% as Latino. There is evidence that the demographics of the powerful elite are changing, as sociologist Shamus Khan argued in a 2012 article. Nevertheless, the one percent is still predominantly white and married.

Gender Income Dynamics in the Top One Percent

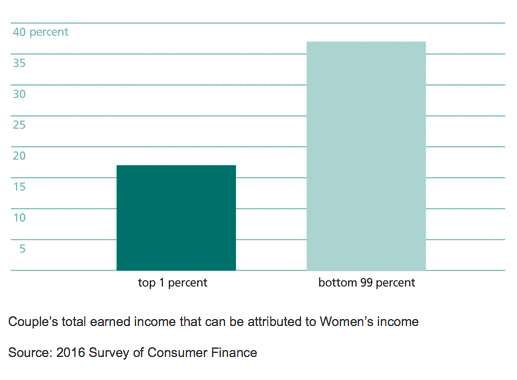

Although women are well represented in the one percent, there are stark disparities between men’s and women’s income in these married households. Whereas women’s income contributes, on average, 37% of a couple’s total earned income in the bottom 99%, SCF estimates show that in the one percent, women’s income contributes, on average, only 17% of a couple’s total earned income (see Figure 2). The gender gaps in income are, thus, substantial and larger in married one percent households than the rest of married households.

Moreover, women rarely make it to the one percent based on their own income. In a 2019 study in American Sociological Review that we conducted using similar data, we showed that women’s income alone is sufficient to qualify for one percent status in only 4.5% of one percent households. More broadly, women’s income is necessary to achieve one percent status in only 15% of all one percent households, which means 85% of one percent households do not depend on women’s income to be in this elite groupThus, white, heterosexual, married men are overwhelmingly the income breadwinners in one percent households, and income differences are stark between partners in one percent households.

Even when women do make it to the one percent based on their own income, they still may not be the top earner in their household. Indeed, among women who earn enough income to qualify for one percent status on their own, nearly a quarter of them are also married to men whose income similarly qualify. In contrast, men have more disparate spousal incomes than women and marry a high-income woman only 3% of the time.

What are the Broader Implications of Gendered Income Dynamics of the One Percent?

Broader implications inside the household. The financial resources that each partner brings to a marriage help determine who has power in that relationship, particularly power in major decision-making. For example, as prior research indicates, the person with the greater income in a relationship often determines where a couple lives, the amount of childcare and housework the other partner does, and importantly, which charities and political campaigns the couple financially supports. Given that men are overwhelmingly the breadwinners in these one percent households, they likely hold the vast amount of power when it comes to most major decisions a couple makes.

Not surprisingly, large income differences between working age (25-64) women and men are associated with traditional work arrangements, where women have low employment rates. When men earn enough income to qualify for one percent status on their own, they have an employed spouse only 29% of the time. Importantly, these patterns differ drastically from the general public (bottom 99%) in which women are employed in 68% of households in this age group. They also vastly differ from spousal arrangements of women who earn enough income to qualify for one percent status on their own. In these cases, women’s husbands are employed 84% of the time. In other words, when women earn enough money to qualify for the one percent on their own, they rarely have access to a non-employed partner who likely performs the vast majority of housework and childcare, and/or manages the outsourcing of these activities.

These income differences in the one percent suggest that women with highly successful careers may still be expected to make work-related compromises because they are part of a dual-earner couple. Indeed, Rachel Sherman, in a 2018 study of individuals in affluent households in New York City, found that women with elite educational credentials were often encouraged or incentivized to scale back their careers because their incomes, though high in absolute terms, still paled in comparison to their husband’s incomes.

Similarly, 2014 research by Robin Ely and colleagues found that in a large survey of graduates from Harvard’s MBA program a majority of men expected that their careers would be prioritized over their spouse’s careers and that their spouse would handle the majority of childcare and housework. These expectations differed dramatically from women with Harvard MBAs who typically expected that their own and their spouse’s careers would be equally prioritized, and that housework and childcare would be shared by both partners. Importantly, men were significantly more likely to report that their expectations regarding the priority of their careers later came to fruition. In contrast, although some women reported that their egalitarian expectations were met, these aspirations for equality went unrealized for many other women. Notably, virtually no women said their own career was favored over their husband’s.

Broader implications outside the household. Identifying the person whose income dictates a household’s elite status is also important because the top earner is likely to have greater social status and influence outside the household than their spouse. Political influence, in particular, is likely to vary between breadwinning and non-breadwinning spouses and is critical to consider because of its potential to shape legislative and judicial actions that have implications for most American households.

The one percent has disproportionate access to politicians and high-powered lobbying firms. Members of the one percent also donate large amounts of money to political campaigns, fund influential super PACs, and help to elect particular politicians. For example, we draw on an important 2013 study conducted by Benjamin Page and his colleagues on members of the top one percent in the greater Chicago area. Their sample consisted mostly of white men. The study found that about half of all members of the one percent had made substantive contacts with either their district’s senator or representative, another representative or senator not in their district, executive branch official, white house official, or official at regulatory agency. Page and colleagues also foundthat two-thirds contributed money (nearly $5,000 on average) to political campaigns or PACs in the last year, compared to only 14% of the general public (in which most Americans donated less than $100).

The one percent has disproportionate access to politicians and high-powered lobbying firms.

Not surprisingly, given their governmental access and contributions, the political viewpoints of the elite more closely align with senator roll-call votes and implemented governmental policy. Martin Gilens details this fact in his 2012 book on the strong link between political viewpoints of the rich—which tend to be more conservative than the general public—and corresponding governmental policies. Indeed, Page and colleagues in their study of elites in the Chicago area found that they expressed more conservative viewpoints than the average American with respect to key policies pertaining to taxation, social welfare programs, and economic regulation. Likewise, using data from the General Social Survey, Page and Hennessey in 2010 found that affluent individuals (defined in their study as members in the top four percent income group) tend to be more conservative than other Americans on economic matters. It is clear that members of the one percent play an important, and likely conservatizing, role in our political system, but who exercises this influence?

Most prior research on elites takes a gender-blind approach, ignoring how gender informs who exercises this power and the ideologies that shape this influence. Scholars generally refer to top income households without making explicit that access to politicians and decision-making on political contributions is likely primarily or only extended to breadwinners in the one percent. Women in one percent households, whose income is largely not responsible for the household’s elite status and who in many cases are not employed, likely have significantly less authority over the direction of political campaign contributions and do not have the same high-powered connections or influence as their breadwinning husbands. Because prior scholarship on the viewpoints of the rich have nearly exclusively focused on men’s ideologies or studied men and women together without analyzing gender differences, whether elite women’s viewpoints vary from elite men’s viewpoints remains an outstanding question. Nevertheless, what is clear is that U.S. politics and the corporate sphere continue to be heavily influenced by a small subset of rich, white, married men, who have particularly conservative economic viewpoints.

Another broader implication of income disparities between women and men in the one percent is an exaggeration of gender roles, with impacts that might extend beyond the home. For example, the traditional gender dynamics that characterize their spousal relationships may influence gender relations in the workplace. Based on multiple studies with nearly 1,000 married, heterosexual male participants, Desai and colleagues in 2014 found that men in traditional marriages with stay-at-home spouses had more negative and biased views toward women in the workplace. Given the extensive authority that many men in the top one percent have in the corporate sphere, traditional roles in their own homes (that may entail women’s subordination) could carry over to how they treat and evaluate the performance of women co-workers and staff.

More generally, this image of exaggerated traditional roles at the top could intensify negative stereotypes that women will “opt” out of paid work when they have economically successful spouses. These negative stereotypes could make it more difficult for ambitious women, who often are married to successful men, to advance professionally or secure coveted positions such as those in elite financial or law positions. Rivera and Tilcsik (2016), for example, found that elite law firms were less likely to call back highly qualified women for job interviews than comparable men, in part, because lawyers perceived that higher-class women were less committed to full-time careers.

Taken together, traditional gender norms in the home and gendered biases in the workplace may act as a reinforcing cycle that curtails even really successful and ambitious women from attaining substantive positions of power.

Why is Gender Diversity Among High-income Earners Important?

The fact that an inordinate amount of economic resources and power is concentrated among a small subset of households is a major societal problem and one that needs addressed. Simply diversifying the breadwinners in the one percent (i.e., replacing men elites with women elites) will not solve the critical issue of inequality between this group and all others. Nevertheless, greater diversity at the top may have significant implications for politics and beyond. Indeed, identifying who has access to political power and influence is important because if more women made it to the one percent based on their own income, they might exercise it differently than elite men. That is, if women’s income was responsible for a household reaching one percent status, the household may make different political contributions and exercise their political influence differently.

First, although there is no research evidence regarding ideological differences between elite women and men, we speculate that high-income women, on average, have more liberal beliefs than their male counterparts for several reasons. Women are often socialized to develop pro-social and cooperative, rather than ego-centric and individualistic, viewpoints and practices; and women’s experiences with gender inequality may add to this socialization and heighten their sensitivity to other forms of inequality. Also, women who make it to the one percent based on their own income tend to have relatively high educations, often advanced degrees, and extensive job experience. Research indicates that women with these educational and labor force characteristics have higher rates of feminist attitudes than men with similar characteristics and that women consequently tend to vote more often for Democratic candidates than men. Diverging life views may increase the likelihood that women help and lobby on the behalf of groups other than their own (i.e., the one percent), even if they remain more economically conservative than non-high-income women.

Second, high-income women and men contribute differently to political causes and campaigns. For example, a 2018 study conducted by Jennifer Heerwig and Katie Gordon that examines U.S. political contributions over $200 (which are predominately made by higher income individuals) show significant gender differences in the types of PACs that women and men donate to. Of men who donate to PACs, two-thirds donate to industry-affiliated PACs (PACs that likely promote their own business and/or financial interests). Although women also support industry-affiliated PACs (though at a 20-point lower percentage), the top PACs that women donate to are ideological PACs, with EMILY’s List, MOVEON PAC, and Hollywood Women’s PAC ranked as the most highly donated PACs by women. Notably, all three of these PACs promote and lobby for more liberal and progressive policies; two of them specifically lobby for greater political representation of women and for gender equality. Likewise, the 2018 US Trust Study of High Net Worth Philanthropy—a nationally representative random sample of 1,600 wealthy households—shows that high-net worth women are more likely to donate to organizations that focus on gender-related issues, like violence against women and reproductive rights.

Taken together, this work suggests that high-income women could potentially exercise influence in more liberal ways than high-income men. Similar arguments could be made if more people of color occupied top income positions in the United States, given that they (particularly African Americans) tend to hold, on average, more progressive viewpoints than whites on issues surrounding economic policies and inequality. Although we need additional research to confirm these speculations about the one percent, it is reasonable to assert that perspectives from women (and people of color) remain substantively missing from the ideological lobbying efforts and political contributions of the one percent.

Conclusion

In this piece, we highlight that white, heterosexual, married men earn most of the income in one percent households, a population that is critical to the structure of inequality. Because the one percent controls disproportionate quantities of resources, it follows that these men have disproportionate power both in and out of the household. Moreover, one percent households are more traditional in their financial and work arrangements than other households at lower income levels. As we explained, these patterns have significant implications. It means that a small group of homogenous men likely exercise the majority of corporate and political power associated with economic elites. It also means that women’s access to the one percent is predicated on a gendered and heteronormative, male breadwinner model and that gender roles are exaggerated among this highly visible and influential group. These traditional dynamics could have ripple effects into other spheres, affecting gender relations in the workplace and conservatizing the political and corporate policies that elites champion.

RECOMMENDED RESOURCES

Ely, Robin J., Pamela Stone, and Colleen Ammerman. 2014. “Rethink What You ‘Know’ about High-Achieving Women.” Harvard Business Review92 (12): 20.

Gilens, Martin. 2012. Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Khan, Shamus Rahman. 2012. “The Sociology of Elites.” Annual Review of Sociology38 (1): 361–77. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145542.

Heerwig, Jennifer A., and Katie M. Gordon. 2018. “Buying a Voice: Gendered Contribution Careers among Affluent Political Donors to Federal Elections, 1980–2008.” Sociological Forum. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12444.

Yavorsky, Jill, Lisa A Keister, Yue Qian, and Michael Nau. forthcoming. “Women in the One Percent: Gender Dynamics in Top Income Positions.” American Sociological Review.