It’s High Time

Every month since the fall of 1982, Irvin Rosenfeld receives 300 joints, around nine ounces of pot, courtesy of the federal government. Packed tightly in a tin canister, they are delivered via Fedex to a local pharmacy. The Fort Lauderdale stockbroker, now 60, suffers from a degenerative bone disease—multiple congenital cartilaginous exostoses—that causes painful tumors, a condition he believes to be much relieved by smoking marijuana. What’s more, he credits it with arresting the growth of the tumors and allowing him to live a relatively normal life. The pot itself is grown on a 12-acre federal farm at the University of Mississippi, the sole producer of federally legal marijuana since 1968. The plants are stored in a massive and securely guarded steel vault and then sent to Raleigh, N.C. where they are dried and prepared and rolled.

And yet, the government that provides Rosenfeld with the drug still classifies marijuana as a Schedule 1 substance. This puts it on par with heroin, LSD, and ecstasy, but renders it more dangerous than cocaine. It also makes research outside the narrow confines of the University of Mississippi’s lab nigh on impossible. The federal government claims with unyielding certainty that cannabis has no “accepted medicinal use.” Why then does it play the part of small-time dealer to people like Rosenfeld?The answer has to do with a narrowly defined “compassionate protocol” of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Investigational New Drug Program (IND). The program was started in the late ‘70s when another Floridian, Robert Randall, successfully argued that pot was essential in treating the glaucoma he had suffered since his teens. First, however, Randall had to fend off cultivation charges after the pot he grew on his sun porch was discovered in a raid on his neighbor’s house. Armed with cache of supporting research—including the results of exhaustive tests he had undergone—Randall argued that marijuana had kept him from going blind. The criminal charges against him were dismissed when D.C. Superior Court Judge James A. Washington determined with poetic succinctness that “the evil he sought to avert, blindness, is greater than that he performed.” (One can still quibble with the implication of maleficence in cultivation and self-treatment.)

Later, in 1978, Randall sued the federal government to obtain legal access to federal pot supplies. This resulted in an out of court settlement that provided him prescriptive access to pot and formed the legal basis for the Compassionate IND program. Randall was the first legal medical marijuana patient since cannabis prohibition began in 1937.

The government began supplying a handful of patients suffering from glaucoma and cancer with cannabis. The program was then expanded to include HIV-positive patients in the late 1980s. At its height, the program enrolled thirty patients. It stopped accepting new patients in 1992, and only four patients continue to receive cannabis from the federal government. Randall was also a prominent figure in a 1987 lawsuit that led the DEA’s chief administrative law judge to conclude that marijuana is “one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man.” The decision was, of course, ignored by the DEA. Such frustrations led legalization activists to turn to the polls and state ballot initiatives.

There are 23 states with laws allowing access to medical marijuana and 18 states that have decriminalized pot, including four states that have legalized the drug for recreational purposes. (It still actively prosecutes suppliers in those states—though the Obama administration has shifted policy away from prosecuting medical marijuana dispensaries in states where its distribution is legal.) All told, around a million Americans use pot legally to treat an ailment.

As for Randall, he never did lose his sight, though he died of AIDS-related complications in 1991. Rosenfeld reckons he has smoked over 200 pounds of government pot—somehere north of 130,000 joints. What’s rather interesting is that both Randall and Rosenfeld’s love for cannabis is Platonic: they claim not to get high from smoking; it’s purely medicinal. As Jake Browne explains in his piece, they may be right: not all weed is the same. Strains can be grown with varying levels of tetrahydrocannabinol, THC, the chemical responsible for “highs,” as well as cannabi- diol, a non-psychoactive chemical that can purportedly suppress seizures. So you can make an effective medicine and you can make a pleasurable drug, or both at once.

Efforts to develop effective medication are severely curtailed by federal policy. The DEA, for example, has only issued a single license for the cultivation of marijuana for research, and that to the lab in Mississippi. But as frustrating as the situation is for research, the criminalization of marijuana has been even more disastrous in terms of lives wasted. According to the ACLU, there were over 8 million pot arrests in the U.S. between 2001 and 2010 and about $3.6 billion a year is spent on enforcing marijuana laws. Enforcement is deeply inflected by racial bias, as the brunt of failed War on Drugs policies falls most heavily on communities of color. Marijuana use is roughly equal among Blacks and Whites, yet the former are 3.73 times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession.

In the meantime, the popularity of the War on Drugs—with its mandatory minimum sentences for possession, its militarized policing, and its mighty contribution to the national trauma of mass incarceration—has plummeted. This displeasure with the status quo, Craig Reinerman argues, is not just some incho- ate sentiment. Rather, the hard work of sympathy-gathering, conscience-raising, and coalition-building has converted that outrage into something like a social movement pushing for policy reform. We might even take some grassroots pleasure in the fact that most of gains have been at the state and local levels, and that federal mandates are increasingly seen as irrational. Change is in the air.

But as Wendy Chapkis reminds us, the same air is as suffocating as ever for Drug War casualties behind bars. It is thus imperative that any reform efforts take their plight into consideration. The commuting of sentences for low-level offenders and the expunging of drug-related blemishes from criminal records, which hugely diminish one’s employment and education prospects, are some ideas that come immediately to mind. Otherwise, any solution to the problem of prohibition will likely splinter along the familiarly depressing lines of race and class. Nonetheless the pressure for reform today is very real, and it suggests a future in which people mightn’t suffer so needlessly under the Draconian policies of the past.

- Prohibition and Its Discontents, by Craig Reinarman

- Terms of Surrender, by Wendy Chapkis

- Please, Think of the Children, by Jake Browne

Prohibition and Its Discontents

by Craig Reinarman

Opiate addiction is on a rampage, from Oxycontin to heroin. Overdoses have quadrupled since 2000 and are now the leading cause of injury-related death. “Synthetic marijuana” is putting people in the hospital, while HIV/AIDS is spreading rapidly among injection drug users in Indiana. The most notorious drug kingpin has escaped from Mexico’s most secure prison. If asked to design headlines to fuel the War on Drugs, one could hardly do better.

So, why is public support for the Drug War is at its lowest in decades? Punitive prohibition has come under increasing criticism as costly, inhumane, and ineffective. In July 2015, President Obama commuted the sentences of 46 non-violent drug offenders and proclaimed to the NAACP that harsh drug laws and the imprisonment they spawned were bad policy: “Mass incarceration makes our entire country worse off, and we need to do something about it…. For non-violent drug crimes, we need to lower long mandatory minimum sentences—or get rid of them entirely.” The next day, former President Clinton criticized a Draconian drug law he once boasted about: “I signed a bill that made the problem worse, and I want to admit it.” Only recently, these sentiments would be blasphemous; now they only echo shifts in public sentiment bubbling up from below.

In the Reagan years, hysteria about crack cocaine intensified the Drug War, including the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which helped lay the foundation for mass incarceration with mandatory minimum sentences of 5 years for possession of 5 grams of crack, often sold on inner-city street-corners. (It took 100 times that amount of cocaine powder, used mostly by more affluent Whites, to trigger the same sentence.) The new law eliminated parole and got whole families evicted from public housing. In a frenzy of bipartisanship, the House passed it 392-16 and the Senate 97-2.

The first Bush administration ratcheted up the Drug War and the Clinton administration added more funding and police to it. Marijuana possession arrests nearly doubled to over 700,000 a year between 1992 and 2000. The Drug Czar’s budget increased ten-fold between 1980 and 2008—as did the number of drug offenders in prison, rising from roughly 50,000 to 500,000 over the same years. An Urban Institute study found that harsh drug laws led to less probation, more prison, and longer sentences, resulting in the most massive wave of imprisonment in U.S. history. The prison population quadrupled, giving the U.S. the world’s highest incarceration rate.

According to FBI and Bureau of Prisons reports, all this hit people of color hardest—far out of proportion to their drug use, which is slightly lower than that of Whites. Discriminatory arrest patterns and the crippling holes left in families and communities by mass incarceration made drug laws the most potent form of racial oppression in America. Drug policy was transformed into a major civil rights issue. Today there is fierce new energy around drug policy reform.

Over the last two decades a cornucopia of such reform efforts have solidified into a global social movement. Since 1996, 23 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws allowing marijuana for medical purposes. In 2012, movement activists waged successful campaigns in Colorado and Washington to legalize all marijuana use. In 2014, voters in Oregon and Alaska passed similar “tax and regulate” marijuana legalization measures. California reformers will put marijuana legalization on their state’s November 2016 ballot.

In 2009, a coalition of activists pressured New York legislators to undo the harshest features of Rockefeller-era drug laws. Then Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, reducing the racialized 100-to-1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses. In 2014, Senator Richard Durbin (D– IL) introduced the Smart Sentencing Act (still under debate, but co-sponsored by members of both major parties), which would cut mandatory minimums for federal drug offenses in half.

The movement has also worked to keep drug offenders out of prison and to get them the help they need. Reformers in Seattle built an alliance of police, prosecutors, and politicians to pioneer the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion Program (LEAD), explored in the Summer 2015 issue of Contexts, which allows police to redirect low-level drug offenders to community services before arrest. An independent evaluation by University of Washington scientists found a 58% reduction in recidivism among LEAD participants compared to a control group. Drug policy reform can improve public safety. The LEAD model has been adopted by Gloucester, MA, a small fishing port. In an open letter, Gloucester’s Police Chief Leonard Campanello wrote, “Any addict who asks for help will NOT be charged.”

The drug policy reform movement now has more organizations, members, and money than ever before, led by the Drug Policy Alliance in coalition with other non-profits. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws has 165 chapters in 46 states, 13,000 paid members, and a social media footprint of 1.2 million subscribers. Families Against Mandatory Minimums has been especially influential regarding the human costs of incarceration. Students for Sensible Drug Policy has grown to 100 chapters in 41 states. Americans for Safe Access, founded by medical marijuana patients in 2002, now has 30,000 members in 40 states. And Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) was started by former narcotics officers whose front-line experience persuaded them that legalization was the only solution. Approximately 10,000 former police have joined LEAP across the U.S. and 90 other countries.

The movement has also attracted some unusual political bedfellows. The financial crisis of 2008 drew in some on the Right who, until recently, had never met a tough drug law they didn’t like. Now, conservatives worried about the size and cost of the state have joined liberals focused on social justice in pushing drug law reform. Who knew the Koch Brothers could find common ground with the Center for American Progress, or Newt Gingrich with Van Jones?

Globally, a growing number of nations have made partial defections from U.N. drug control treaties, fracturing the 50-year old consensus around criminalization. Portugal decriminalized all drug use in 2001. Uruguay legalized the production of cannabis in 2014. Even traditional Drug War allies in Latin America are now in what journalist Alma Guillermopreito calls “open rebellion” against U.S.-style prohibition.

Underlying all this is the cultural force of a broad political constituency that sees drugs as technologies of the modern self. Illicit drug use is no longer the province of the marginal and deviant. Educated, employed, engaged citizens around the developed world see drug use as rather normal. They are harder to stigmatize and silence, and they are showing up in voting booths.By exposing the full costs and consequences of punitive prohibition, the drug policy reform movement has pushed drug policy to an historic inflection point. The Drug War consensus has collapsed. What is emerging to take its place are more harm- reduction programs like syringe exchange, treatment in lieu of prison, and further legalization. All legalization initiatives thus far, however, have been at the state level; marijuana possession remains a federal crime. The Obama administration has allowed these laws to stand. But if the next president is less sympathetic, we may be in for a constitutional confrontation.

Terms of Surrender

by Wendy Chapkis

Marijuana prohibition can seem like a joke, especially to people like me—White, middle-class Americans living in politically progressive (and often cannabis infused) communities such as coastal California, where I grew up, or Southern Maine, where I now live. For many like us, “Reefer Madness” seems a ridiculous relic of a much less enlightened age. Stoners and dealers—from Cheech and Chong to Harold and Kumar and on to the Pineapple Express—are funny, not dangerous felons.

And then maybe someone we know gets arrested. For me, it was my friend Valerie, a member of that least-likely-to-be-arrested demographic: an economically secure White woman living in that most liberal of enclaves: Santa Cruz, California. Because she was growing five marijuana plants in her home garden, she was charged with felony cultivation. As I quickly learned, far from being a joke, marijuana prohibition is an ongoing horror show. It involves almost 700,000 arrests each year, 88% of them for possession. Huge numbers of Americans are being imprisoned, sometimes for decades, for marijuana offenses. In fact, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, at least 69 people are serving life sentences for non-violent pot crimes.

Marijuana prohibition, moreover, has been absolutely central to the draconian War on Drugs. According to the Pew Research Center, almost half of all Americans have tried marijuana; in contrast, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, less than 2% have ever used heroin. Marijuana is the only illicit drug used by large enough numbers of Americans to justify a massively expensive federal anti-drug bureaucracy and a militarized police force.

Marijuana prohibition has made a significant contribution to mass incarceration, disproportionately of Black Americans, helping to make the U.S. “the world’s most highly incarcerated society in history.” Children have been removed from the custody of their marijuana-using parents; homes have been seized using asset forfeiture laws; students convicted of marijuana offenses have been denied federal scholarship aid; and patients have been punished for using a substance their physicians, research scientists, and now even CNN’s Chief Medical Correspondent Sanja Gupta believe would help.

But, finally, state by state, this prohibitionist approach to marijuana has begun to collapse. In 1996, California passed the nation’s first medical marijuana law; there are now 23 states where authorized patients are allowed to legally access and use cannabis. In 2012, marijuana prohibition took another major hit when voters in Colorado and Washington legalized adult recreational use of marijuana. Two years later, in 2014, Oregon, Alaska, and the District of Columbia also voted for full legalization. It is likely that in 2016 additional states will vote to regulate and tax adult recreational sales and use of cannabis.

For the first time, more than half of all Americans now say that marijuana should be legalized. It increasingly appears to be true, as long-time marijuana activist Michael Corral argues, “the war against marijuana is over; now we are just negotiating the terms of surrender.” But before we declare victory, it’s important to remember that the devil is always in the details.

“Legalization” can mean radically different things. In the Netherlands, marijuana is currently available for legal purchase in small, independently owned “coffee shops” scattered throughout the country. Canada, on the other hand, has been attempting to centralize all legal (currently medical) marijuana cultivation in the hands of only a dozen industrial growers and distributors for the entire country.

In the United States, legalization looks very different in the states of Washington and Colorado. In Washington, voters surrendered the right to cultivate cannabis at home in exchange for legalized sales and use. In that state, marijuana consumers must purchase their cannabis through a small number of licensed distributors. In Colorado, individuals growing a few plants for themselves exist alongside small commercial cultivators and large industrial operations.In other words, policy differences produce very different outcomes. It can seem trivial to debate competing legalization proposals in the face of the very real and very serious problems of prohibition. But it is also useful to remember that it can be difficult to undo, or redo, bad legislation. Take, for example, the end of alcohol prohibition. As Jon Walker notes in his book After Legalization, the 21st Amendment ended federal prohibition, but states made very different decisions on how to regulate alcohol. Not only did a third of states continue to outlaw it entirely, even states that permitted the production and sale of alcohol generally didn’t allow producers to sell directly to consumers. The result was the consolidation of production in the hands of a few very large companies. This, Walker reminds us, “was not some natural end state created by the invisible hand of the market. It was a policy choice. The government adopted regulations that disadvantaged small producers and made new startups almost impossible.”

This is important to reflect on when we think of “regulating marijuana like alcohol.” Which version of alcohol regulation are we referencing and what outcome do we desire? It wasn’t until 1982, when California changed its liquor laws to allow small breweries to sell directly to consumers in “brew pubs” that the “micro-brewery revolution” began. In 1983, there were only 80 breweries in the entire U.S. By the late 1990s, hundreds of new breweries were founded every year.

So what terms of surrender should we demand in the failed war on cannabis? Should consumers be able to purchase pot directly from growers through a community supported agriculture (CSA) model of cultivation? Should local, small-scale growers be protected from competition with large corporate cultivators? Should we be allowed to grow for ourselves? And, even more importantly, how do we begin to undo the damage inflicted by the War on Drugs, including the problem of prisoners of war?

Without a robust policy for releasing drug war prisoners, there is a real risk that legalization of marijuana will mean that a few White men (in a still male-dominated industry) will make a lot of money on cannabis cultivation and sales, while many Black men (almost 4 times as likely as Whites to be arrested for marijuana possession despite similar rates of use) will remain behind bars or carry felony drug convictions forward. President Obama has recently begun a conversation about the need for the reduction or elimination of mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent drug crimes, for an end to the practice of asking job applicants about their criminal histories (“ban the box”), and for the restoration of voting rights for felons who have completed their sentences. In July 2015, he even commuted the sentences of 46 low-level drug offenders. These are all important first steps. But there are tens of thousands more incarcerated people who need their marijuana sentences commuted and hundreds of thousands who need their records expunged.

Certainly marijuana legalization in itself is better than policies of prohibition and criminalization. It may even represent a significant blow to the War on Drugs apparatus. But it is equally possible that marijuana legalization could be to the Drug War what marriage equality is to the queer liberation movement: a celebrated step toward social justice but not the only—or even, arguably, the most important—one.

Please, Think of the Children

by Jake Browne

If someone had told you a decade ago that children would become the driving force behind the medical marijuana movement, you’d likely think they were high. Yet in 2015, we witnessed 15 states—including conservative bastions like Alabama and Texas—pass legislation designed primarily to give seriously ill minors access to cannabis. It has become one of the most fascinating developments as the concept of legalization becomes normalized, and it shows no signs of slowing down.

As marijuana moves into the mainstream, so too do growing techniques. For decades, underground black market cultivators have bred for high amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) that provide the strongest high, whether that be a sedative body effect or a racing mental buzz. If something didn’t get you “stoned,” that would be the end of the line for that particular plant. Enter high-end testing laboratories with the onset of medical marijuana. Suddenly, scientists were finding cannabinoids (chemical compounds in weed) that were much more interesting than THC. The biggest cash cow in the industry was suddenly cannabidiol, or CBD, which showed a diverse range of medical applications as an antiemetic and anticonvulsant, among others. The only problem: it doesn’t get you high. Growers had been axing the best medical marijuana plants for years.

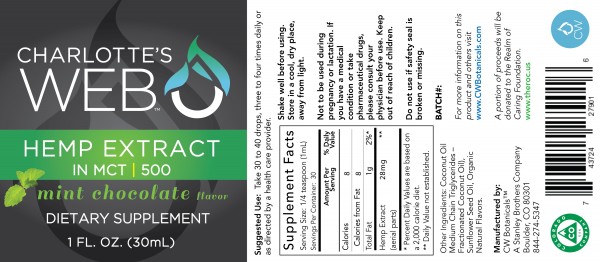

What came next amounted to an arms race. With plants taking around four months from seed to smoke, finding CBD-rich strains of marijuana became paramount for those looking to jump into the emerging market. Some began tapping the industrial hemp market to find the compound, while others simply began testing their existing supply. One of the fastest to market, however, was Charlotte’s Web, a type of marijuana named after the popular book as well as Charlotte Figi, a now 8-year-old girl who suffers from Dravet syndrome. It quickly became one of the most controversial.

In a nutshell, Dravet syndrome is characterized by a large number of epileptic seizures starting at about six months of age. Charlotte’s parents heard of another child using medical marijuana to treat the symptoms and soon wound up working with Realm of Caring (ROC), a nonprofit based in Colorado that has a proprietary strain of high-CBD cannabis. They immediately noticed a dramatic decrease in the frequency of her seizures and improvement in her quality of life without the euphoria traditionally associated with weed. Soon, parents across the country were clamoring for similar strains to help their children. With limited supplies and communication issues at ROC, these recent transplants grew frustrated.

Other strains—with names like Cannatonic and Harlequin—began popping up, but few companies had the marketing resources and constant media attention to make them household names like Charlotte’s Web. Families without access to or knowledge of these strains soon began lobbying for medical marijuana laws in their own state, but under a different guise than many: bills that would allow for CBD oil and not strains high in THC. The legislation, heralded by some, was decried by others as insufficient for many patients.

Dubbed “the entourage effect”, advocates argue that we don’t fully understand the interaction between various cannabinoids, including CBD and THC. Championed by Israeli researcher Raphael Mechoulam, this approach favors whole plant medicine as opposed to isolated cannabinoids. Take, for instance, Marinol, the FDA approved synthetic THC. While raw marijuana has never been directly attributed as a cause of death, Marinol has. Four times, in fact. Scientists believe there’s a synergistic effect that isolated CBD alone cannot provide and CBD-only laws are a disservice to those who need medical cannabis.

That hasn’t stopped the market from producing a wide variety of CBD products, many offering to ship across the nation because they claim to be derived from hemp. This remains a violation of the Controlled Substances Act, but patients with no other recourse are willing to take the risk, driving up prices for the limited supply. These companies are also in a bind as to how they can market their lines, with several receiving a February 2015 letter from the FDA warning about making claims of efficacy. “Consumers should beware purchasing and using any such products,” the FDA noted. Of the product lines they tested, most came back with fractions of a percent of CBD. Patients were purchasing the equivalent of snake oil.As with any nascent industry, there will be growing pains. New extraction methods, coupled with breeding projects, should help accelerate the process of finding medically appropriate strains for patients. For now, those in states with CBD-only legislation may find treatment insufficient and give up on marijuana altogether. Moving forward, whole plant cannabis laws, including industrial hemp, are the only way to pave the road to the future. Otherwise, patients will continue to flock to legal states where they’re left without a support system or resources. Will someone please think of the children?