Measuring Same-Sex Relationships

When social scientists need information about demographic trends, they immediately turn to the U.S. Census Bureau, the most highly regarded collector of data on Americans’ rapidly changing lives. However, even the Census Bureau faces challenges in measuring certain trends. At the national level, Census Bureau scientists must ask their questions within the confines of federal restrictions. At the individual level, Census Bureau researchers must frame their questions in ways their respondents will comprehend, even as terms commonly ascribed to some populations are rapidly changing. The measurement of same-sex relationships challenges Census Bureau experts on all of these fronts.

Measuring Family Ties

The measurement of family relationships, living arrangements, and marital status has a long history at the U.S. Census Bureau. Over time, the census categories have changed to reflect changes in U.S. society and laws that define the institution of marriage and other legal and non-legal relationship statuses. In fact, how the census measures marital status has evolved for more than a century. In 1880, the categories consisted only of single, married and widowed/divorced. By 1890, widowed and divorced each became its own category and in 1950, the category of separated was added. For the relationship item, instructions for enumerating roommates, boarders, and lodgers go back to the nineteenth century. In 1980, the form added a combined partner/roommate category, and in the 1990 Census, the category of unmarried partner was included for the first time.

Family Diversity Projects creates and distributes traveling photo-text exhibits

featuring members of the LGBT community. Photos © Gigi Kaeser

Recently, challenges in accurately measuring relationships have involved the growing recognition of same-sex couples. Unlike other countries such as Britain and Canada, U.S. laws recognizing same-sex couples vary. At the federal level, there is no legal recognition while state laws range from no legal recognition to full marriage equality. Passage of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in 1996 had ramifications for how federal statistical agencies count same-sex couples. DOMA requires the federal government to define marriage as a legal union exclusively between one man and one woman. Partly in response to DOMA, for Census 2000, an edit procedure was introduced whereby same-sex couples who checked husband or wife were automatically reallocated as unmarried partners.

When the Census Bureau announced in 2008 that the same edit procedure would be used in the 2010 Census, gay advocacy groups took notice. A coalition of many different lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) groups formed a census advocacy campaign known as Our Families Count. Groups lobbied for the Census Bureau to tabulate same-sex couples as they had originally reported on their census forms. In 2009, the Census Bureau announced that, while the Census 2010 tabulations would still reflect the unmarried partner re-edit classification, the agency would produce state-by-state counts of same-sex couples who identified themselves as spouses.

Because the laws governing same-sex marriage are fragmented and constantly evolving, the federal statistical system faces an enormous challenge to accurately reflect today’s increasingly complex relationship configurations. Given that approximately 42 percent of the U.S. population now resides in an area where some form of same-sex couple recognition is legal, statistical agencies must find a way to adapt their current measures.

Asking Questions About The Questions

To understand how gay and lesbian couples think about and report their relationships on official forms, the Census Bureau sponsored a two-part qualitative research project as part of a federal inter-agency task force. Using focus groups, we first explored the nomenclature of the current relationship and marital status questions — how do gay couples interpret them, what terms are used by this subpopulation, and under what circumstances? This enabled us to develop alternative questions that were then evaluated during one-on-one “think-aloud” interviews. This is how the Census Bureau “cognitively tests” the understanding of questions.

Between January and March 2010, investigators conducted a total of 18 focus groups across seven geographically diverse locations ranging from cities like Boston to rural areas in Georgia. Fourteen groups consisted of individuals in same-sex relationships with members recruited according to relationship status (legally married, in a domestic partnership or civil union, or had no legally recognized status). In addition, four groups consisted of persons in opposite-sex relationships who were not legally married. Members of all groups were cohabiting with their partners.

We first asked participants to describe how they usually introduced their “better halves.” This was followed by a request to complete a form containing the 2010 American Community Survey items of name, relationship to householder, gender, age, and date of birth followed by the marital status question (see questionnaire on next page). Moderators then led a discussion of how participants answered the questions and why. Moderators focused on whether answers were predicated on current legal relationship status, existing laws in their states of residence, whether participants interpreted the questions to be asking about a legal status or something else, and what alternative terms or categories they expected to see on the forms.

Listening to People Think

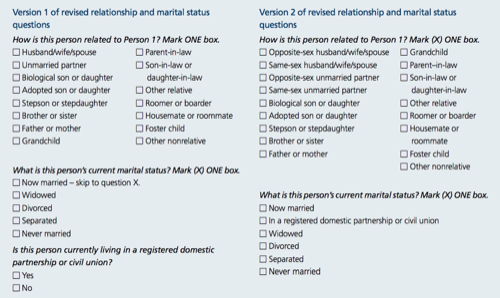

Following the focus groups, we crafted two new versions of the relationship and marital status items. We tested these items using “think-aloud” interview techniques where respondents read questions aloud and verbalize their thought processes as they formulate answers. Forty interviews were conducted in four different cities between March and April 2011. Locales ranged from Washington, D.C. to Charlotte, North Carolina and represented a variety of state laws regarding same-sex partner recognition. Participants were all from cohabiting couples — 15 were straight and the other 25 were gay and lesbian. As in the focus groups, we recruited participants with a wide range of legal statuses ranging from married same-sex couples, same (and opposite-sex) domestic partners, to couples with no legal recognition.

The questionnaire above illustrates the two versions randomly assigned to participants. After completing the randomly-assigned version, participants completed the alternative version followed by a debriefing that also determined which, if any, version they preferred.

We found that gay and straight participants often use the same terms upon introduction. Most often among these were: wife, husband, partner, boyfriend and girlfriend. The term partner was more often ascribed to gay and lesbian relationships (especially by opposite-sex couple groups). We also found that, particularly for gays and lesbians, participants’ use of terms was not static but was conditional upon assessment of the setting. For examples, a gay male from rural Georgia responded, “How would I introduce my partner? It depends on the setting. If it’s this setting, I would say ‘my partner [name].’ If it’s outside, ‘my good friend [name] or ‘uncle.’” So, a “wife” among friends is a “roommate” when the cable repairman comes to the house. Likewise “single” on a flex insurance health plan becomes “married” on a census form.

However, upon probing we found that most participants viewed the census questions through a legal prism, believing it to be measuring state-sanctioned legally recognized relationships. Consequently, most answers aligned with legal couple statuses. Persons in same-sex couples without legal recognition residing in areas that did not recognize gay marriage indicated willingness to select ”unmarried partner” because it was both legally accurate and the word ”partner” was viewed as an adequate descriptor for their relationship. We also found that a legal marriage trumped local laws, at least for participants who had a legal marriage performed somewhere (inside or outside the United States). A lesbian from rural Georgia stated, “Oh, I would check off [wife], absolutely. I don’t care if it would make everybody pissed off, and I really don’t care if it wouldn’t be recognized where I’m at. I don’t care if I was in Antarctica, I would say wife, absolutely.” And a gay male from Ft. Lauderdale commented, “I would still check husband or wife. As far as I’m concerned, I’m legally married, I don’t care what the federal government thinks.”

Encountering Resistance and Confusion

This is not to suggest that all same-sex couples were perfectly happy with the current options, particularly marital status. Participants from same-sex couples who lived in areas where marriage was not allowed and had no legal partnership status viewed the options as “marriage-centric” and without categories to describe their situations. Most marked “never married” and a few marked “divorced.” Gay and lesbian participants who had been divorced from a previous heterosexual marriage felt frustrated that their marital status would be defined by a long-ago relationship unimportant compared to their current relationship.

Likewise, same-sex couples in registered domestic partnerships and civil unions expressed an undercurrent of dissatisfaction because the current options do not allow them to acknowledge the legally recognized component of their union. Overall, many did not feel any of the options adequately reflected their current lives, and felt personally discounted as expressed by comments such as this one, “I can’t answer…this would be blank. I couldn’t answer it because ‘now married‘ would be false in every sense… And ‘never married’ is utterly false to my heart. So I consider this unanswerable. This is one of those forms where no appropriate answer is provided.” Or this one, “If you want accurate information then give me the choice to give you that information. If you’re failing to get that information then the census is not going to be correct to begin with, it’s going to be skewed.”

When presented with the revised questions, respondents were pleased to see the changes that attempted to accommodate their situations: moving unmarried partner to the second response category and disaggregating same-sex and opposite-sex couples. But, we had a concern as to whether there would be sensitivity issues among respondents in opposite-sex couples with the question that disaggregated response categories for same-sex and opposite-sex couples. In particular, we took notice of interviews conducted in Charlotte, North Carolina to gauge this reaction.

One straight white female expressed this view: “This [version] actually might, would offend me a little bit, because I think it’s…I feel like we’re kind of just lowering the standards…[as in] ‘Okay we’ve got to conform to everyone, we want to be politically correct.’ And that just really gets on my nerves, honestly… you know in a different part of the country, you might not be hearing this, but, that’s how I feel about it.” Another straight female stated, “[That version] tries too hard…it’s making a point. [That version means] ‘we’re gonna put it out there…that we’re including everybody’ (emphasis added). But I get that…it’s fine…we’re in America.” However, when pressed directly, neither indicated this opinion would lead them to discard the survey or otherwise not participate. Or, as one put it, “I wouldn’t write my Congressman. I wouldn’t go on Facebook about it…it’s not that deep.” Of course, this is a hypothetical judgment given in the context of a think-aloud interview, so we can only surmise their actual behavior.

The inclusion of the category “In a registered domestic partnership or civil union” in the marital status question revealed a general lack of understanding about the concept among both gay and straight respondents and regardless of legal status. Only a few people said they were unfamiliar with either domestic partnerships or civil unions, but confusion abounded about what they were. One common misunderstanding was equating this concept to gay marriage. “In California you can do a domestic partnership, which is a same-sex marriage.” Another misunderstanding equated it to common-law marriage as in this comment: “It seems like domestic partnership may be you’ve been living together for awhile. I think, legally after five years in North Carolina it’s considered…I can’t think of the term.” Or this one, a civil union is “two people that have lived together for at least seven years.” For these reasons, we recommend a separate question as a means of measuring domestic partnerships/civil unions.

Catching Up to the Future

The social and legal landscape for same-sex couples has changed dramatically since Massachusetts first recognized same-sex marriage. Since then, other states have passed similar legislation as well as civil unions and domestic partnerships for gay and lesbian couples. In this respect, federal agencies have not kept up with the times, and new measures must be constructed to reflect recognition that, in some cases, is intended to confer the same rights and responsibilities as marriage.

In reality, designing a one-size-fits-all federal form when the legal reality of same-sex partner recognition is fragmented poses a challenge for questionnaire designers. However, accurately counting gay and lesbian couples is paramount since legislative bodies, courts, and voters are making decisions that affect the day-to-day lives of this population. Will they receive partner health insurance, Social Security, or pension benefits like their straight couple counterparts? Will they be allowed to adopt children or visit their partners in the hospital?

With the qualitative testing complete, federal agencies should follow best practices and quantitatively test the new questions in an environment that closely resembles a large-scale production survey. Only then can we be certain the data are valid and reliable. Ultimately, the Census Bureau and other statistical agencies must be responsive to social changes so our vital statistics accurately mirror and help support America’s diverse population.

Further Reading

- The Census Bureau page on Same Sex Couples

- Same-sex Couples in Census 2010: Race and Ethnicity, by The Williams Institute

Comments 1

talazraikgb

March 16, 2013Almost certainly almost all of the webpage followers know already the power of any social internet marketing system. What's more, the majority of people know already in which promotional by means of social networking will skyrocket web-site positioning together with enhance your on the net company. So which almost all of the online surfers have no idea is actually -how they may generate the power of social networking to their compact company's edge. These are some suggestions that may help you in ones own social internet marketing tries. The most important thing to not forget when it comes to social internet marketing is that you simply want to create a fascinating together with user generated content. This is the type articles what individuals will want to offer ones own acquaintances together with readers on their interpersonal single pages. Set up articles which can be useful together with significant, actually not a soul will want to promote the application. Helpful articles http://www.garybirkenmdmedicalmysteries.com/ will probably push the attention of this fanatics together with admirers. They can in all probability prefer to promote it all, that could grow your probabilities to become more readers together with potential clients. Result in room in your home when it comes to studies together with glitches in the social networking marketing, specifically in a symptom. Loose time waiting for just what is actually and what's no longer working. Evaluation all. Generate changes as essential. Whatever valuable when it comes to many several other sorts of small organisations will not be right for you. It is advisable to learn on ones own studies together with errors. If you use this type of internet online selling, possibly you have to modify together with renew ones own focus together with objectives often. In in that possition you are likely to stick to objective. Presently right now generally at this time now certainly , truth be told furthermore in that respect so here any countless causes which could take ones own promotional off unforeseen strategies. So it is best to re-evaluate the particular route it is often. Do it right often. Check your campaigns to see what type is regarded as the good. xrtiu6fd8gf