Mental Illness Affects Police Fatal Shootings

Police fatally shot almost 2,000 people in the U.S. from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2016. Much of the news coverage about fatal police encounters has focused on the race of the individuals killed by police, overlooking the fact that a quarter of those killed exhibited signs of mental illness.

We know little about the circumstances surrounding these fatalities. My evidence shows that people with mental illness encounter police in different situations than those without mental illness, and people with mental illness who are killed by police behave differently than those without mental illness. Using this information, we can and should implement programs to reduce fatal encounters between police and people with mental illness.

Individuals with mental illness may exhibit behaviors that are misinterpreted by police as threats, leading to tragic outcomes. These individuals might be experiencing a crisis, unable to comprehend or comply with police commands due to their condition. The presence of mental illness can significantly alter the dynamics of an encounter, necessitating a different approach from law enforcement to prevent unnecessary fatalities. Recognizing these unique challenges is crucial in addressing the underlying issues that contribute to such fatal encounters.

At Resurgence Behavioral Health, a comprehensive approach is taken to support adults experiencing psychiatric, emotional, and substance use problems. By providing tailored treatment and support, Resurgence aims to address the root causes of these issues, helping individuals manage their conditions effectively. This kind of intervention is vital in reducing the likelihood of fatal encounters with police. Programs that focus on mental health can equip individuals with the tools they need to navigate crises more safely and reduce th

The federal government publishes two sources of data regarding fatal use of force by police. The Federal Bureau of Investigation has published the Uniform Crime Reports since 1929, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics has published the Arrest-Related Deaths Program since 2003. However, in 2015, the Washington Post showed that the official statistics did not include half of the fatal police shootings reported in the press. The data also lacked information on the mental health status of individuals killed by police.

After their initial report, the Post tracked incidents of police officers fatally shooting civilians while on duty in the U.S. I used this data in conjunction with data that I collected regarding how fatal shootings by police were initiated. The Post reports the mental health status of the individual killed, whether they were armed, and whether they were attacking police after examining police records. The reliance on police incident reports, which may be subjective or biased, limits the data.

To check the data, I compared information regarding every encounter recorded by the Post against online news reports. Following this process, I adjusted the data where there were discrepancies. For example, I removed two cases where individuals were killed by off-duty police officers. In another case, an individual was recorded as not having mental illness, but news reports indicated otherwise. In the end, I excluded 224 cases because of missing information. My full analysis, available from SocArXiv, breaks down the results by race/ethnicity for African Americans (386), Whites (724), and Hispanics (230). I removed other racial and ethnic groups due to the small number of cases.

Using the Post data as a starting point, I searched online for news reports about how police came into contact with individuals who were subsequently killed. I recorded whether a patrol officer initiated contact, a local police department initiated contact to serve a warrant or as part of an investigation, a SWAT team or U.S. Marshals initiated contact, a friend or family member called 911, the person ultimately killed called 911, or someone else called 911. Examples of each of these six categories:

- Contact initiated by a patrol officer.

Example: “officers on patrol… began following the [car] after they saw the driver make an illegal U-turn.”- Contact initiated by a local police department issuing a warrant or investigating an individual.

Example: “Lauderhill police was conducting an investigation involving a stolen vehicle. When they confronted [the driver] in the stolen Hyundai Genesis he rammed into a marked K-9 cruiser, which had an officer and a K-9 inside.”- Contact initiated by a SWAT team or US Marshals issuing a warrant or investigating an individual.

Example: “he was wanted on a felony weapons charge after he failed to show up to court on Monday… The Riverside County Sheriff’s SWAT team made numerous attempts to get [the suspect] to come out.”- Contact initiated by a family member or friend calling 911.

Example: “[The resident] placed the emergency call that day because of concerning statements her husband was making.”- Contact initiated by someone other than a family member or friend calling 911, typically a stranger.

Example: “Police were summoned… following a 911 call reporting a man smashing windows at a nearby apartment.”- Contact initiated by the individual who was subsequently killed calling 911.

Example: “Officers responded to a 911 call from… a woman saying she planned to shoot her girlfriend and then herself.”

I removed 310 individuals who were killed by police because initiation information was unavailable, then analyzed the remaining 1,340 cases. Of these, 337 cases (25%) involved individuals who had mental illness.

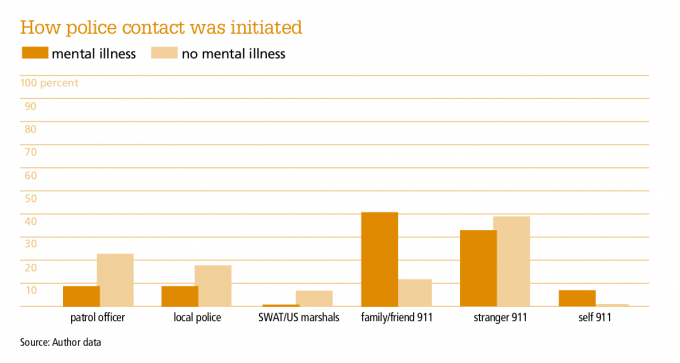

The above figure displays how police contact was initiated as a percentage of cases by mental health status. It shows that the most common cause of police contact for those with mental illness was a call to 911 from a family member or friend (41%). In comparison, a call to 911 by a family member or friend accounted for only 12% of contacts for persons without mental illness. Police-initiated contact accounted for only 19% of contacts with persons who had mental illness, but 48% of contacts with persons without mental illness. Only 7% of contacts with persons who had mental illness were caused by the individual’s own call to 911.

The different patterns of fatal police contact raise issues for policy makers and police departments, in that they likely emerge from how police contact people in nonfatal situations as well as differences in the perceived danger of various types of contacts. Past studies have shown that individuals with mental illness are overrepresented throughout the criminal justice system, with approximately 50% of incarcerated individuals having at least one mental illness. The high prevalence of mental health issues among police-involved fatalities further indicates the value of research on policies to reduce negative outcomes for people with mental illness.

Police departments should also ensure that 911 call operators are able to effectively obtain and convey to first responders any valuable information regarding mental illness as reported by family members or friends calling for help. These close contacts are a rich source of knowledge about the mental health of a loved one, and the information they provide—including insights about triggers, diagnoses, and medication—may help police de-escalate a situation. Emergency call operators should gather information from callers about signs that an individual may be experiencing a mental health crisis, a move the Chicago Police Department has undertaken by training all of their 911 center employees to recognize situations that involve persons with mental illness.

We also need to examine why mental health status affects how fatal police contact was initiated and when family members or friends call 911. Do they only call in the most dangerous of situations, those most likely to result in fatality, or do family members or friends of those with mental illness call 911 more often and create more possibilities for a fatal encounter? I cannot reason backward from the data to explain the differences given that the data only includes police contacts that resulted in death. More research on the mental health status of individuals for all police encounters would help answer this question.

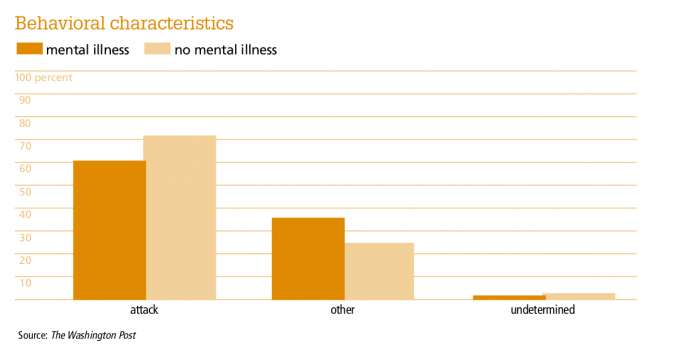

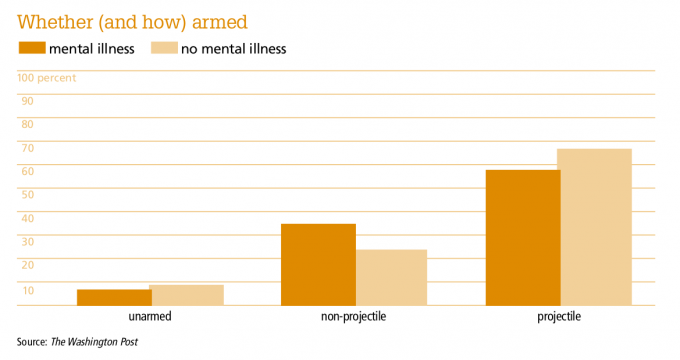

The dangerousness of the encounter could also explain the high rate of fatalities among people with mental health. The Washington Post data includes information about whether and how the individual killed was armed. I created three categories from the original data: unarmed, armed with a non-projectile weapon such as a knife, and armed with a projectile weapon such as a conducted electrical weapon or a gun. I included toy guns in the latter category, because police may have difficulty distinguishing real from toy guns on the scene. The Post also recorded whether the individual killed was attacking police at the time of their death. The following figures display differences in behavioral characteristics as a percentage of incidents by mental health status. In both figures, we see that people with mental illness were involved in less dangerous situations: they were less likely to be armed with a projectile weapon (bottom) and they were less likely to be attacking police (middle).

Because individuals with mental illness were less likely to have a projectile weapon and were less likely to have attacked police, other factors must have figured into the use of deadly force, such as non-compliance. Fears about what happens when individuals with mental illness are not compliant with police orders are widespread among advocates for people with mental illness. The National Alliance on Mental Illness has written about this problem: “When officers believe an individual is deliberately disobeying their instructions, they are trained to increase their compliance tactics. In situations involving someone whose mental illness is preventing him from following officers’ instructions, the stage may be set for a confrontation.”

In addition to training emergency call operators to gather information, police departments should train police officers in de-escalation techniques specifically pertinent to those with mental illness. These techniques include keeping a distance, using a conversational tone of voice, and using mirroring tactics to validate the feelings of the individual in crisis. Research from the National Institutes of Health indicates that when police are trained in these approaches through Crisis Intervention Team programs, arrest rates decline and rates of psychiatric referrals increase. Training can also reduce the level of force used by police.

While these practical recommendations will help reduce citizen fatalities in police interactions, it is clear that better data must be provided if we are to understand how police contact becomes fatal. Researchers in a number of fields have advocated for a national database on police fatal use of force that includes information about the individual killed by police (such as race/ethnicity, age, and gender) and information about the police officers involved (such as rank, education, and complaint history). Basic information about how police contact was initiated and whether those contacted by police were compliant would make these data more robust. Reducing fatalities in police contacts, whether or not the individuals in question have mental health conditions, is a particularly challenging task absent such information.

Comments 1

Bill

August 28, 2018I typed "police shootings mental health calls" into my Google search bar. I found several incidents of police shootings across the US stemming from a law enforcement encounter with a mentally ill individual. This said individual was apparently experiencing an acute exacerbation of his/her illness. When i read the news story covering the shooting I discovered the person who got killed was a young Black male. I didn't see any stories of police shootings occurring in response to a mental health crisis of any other race except for one who happened to be Native American.

I'm hearing on TV and seeing reactionary posts on social media that the apparent reason the officers shot the subject is because he was black. After reading the police statements or reading the findings of an inquest I see that the deceased was being aggressive in some fashion and not redirecting his aggressive behavior.

Nevertheless, police are now on a heightened alert and now associate mental health calls as an unknown and unpredictably dangerous call or has the potential to escalate compared to a shoplifter or even a drunk driver.

I have a bipolar disorder that acts up every few years and i end up needing help. Recently I searched for services and I was told to call 911 who in most all cases is police dispatch. I see that is standard procedure weekends, holidays, and after hours. I'm needing medical aid as I write this and i am aware that people being are being shot in the context of a mental health emergency. I need some medical aid so I called a helpline. I told their operater my problem and asked if I could receive some help.

I was then asked if I "was on the ______ Indian Reservation". I immediately saw my situation and being realistic about these implications I was able to end my call in as best a fashion as I could. My illness got out of hand due to a move plus i havent needed any medical attention in 11 years. There are long wait lists to see a prescriber, others not taking my insurance, and still others are not taking new patients. I live in one of the states " frontier counties" where mental health services are scarce. There is a therapist this county shares with the neighboring county. I tried to get some help at the local urgent care clinic but I was unable to come off as a drug seeker. The provider didn't even bring my chart into the exam room. He started explaining they would not give any drugs. The fact that I most certainly was seeking medication was interpreted in the face of the fact that people have been malingering in order to obtain drugs, probably more than other jurisdictions in my area. I'm ambivalent about taking psych meds as I know how damaging they can be. I'm stuck right now and can only tough things out and take a huge chance on myself getting through this.