Muslims in America

Seven years after the terrorist attacks on U.S. soil catapulted Muslims into the American spotlight, concerns and fears over their presence and assimilation remain at an all-time high.

Recent national polls find that four in 10 Americans have an unfavorable view of Islam, five in 10 believe Islam is more likely than other religions to encourage violence, and six in 10 believe Islam is very different from their own religion. All this despite the fact that seven in 10 admit they know very little about Islam. And yet Americans rank Muslims second only to atheists as a group that doesn’t share their vision of American society.

These fears have had consequences. In 2001, the U.S. Department of Justice recorded a 1,600 percent increase in anti-Muslim hate crimes from the prior year, and these numbers rose 10 percent between 2005 and 2006. The Council on American-Islamic Relations processed 2,647 civil rights complaints in 2006, a 25 percent increase from the prior year and a 600 percent increase since 2000. The largest category involved complaints against U.S. government agencies (37 percent).

Clearly, many Americans are convinced Muslim Americans pose some kind of threat to American society.

Two widespread assumptions fuel these fears. First, that there’s only one kind of Islam and one kind of Muslim, both characterized by violence and anti-democratic tendencies. Second, that being a Muslim is the most salient identity for Muslim Americans when it comes to their political attitudes and behaviors, that it trumps their social class position, national origin, racial/ethnic group membership, or gender—or worse, that it trumps their commitment to a secular democracy.

Research on Muslim Americans themselves supports neither of these assumptions. Interviews with 3,627 Muslim Americans in 2001 and 2004 by the Georgetown University Muslims in the American Public Square (MAPS) project and 1,050 Muslim Americans in 2007 by the Pew Research Center show that Muslim Americans are diverse, well-integrated, and largely mainstream in their attitudes, values, and behaviors.

The data also show that being a Muslim is less important for politics than how Muslim you are, how much money you make, whether you’re an African-American Muslim or an Arab-American Muslim, and whether you’re a man or a woman.

The notion that Muslims privilege their Muslim identity over their other interests and affiliations has been projected onto the group rather than emerged from the beliefs and practices of the group itself. It’s what sociologists call a social construction, and it’s one that has implications for how these Americans are included in the national dialog.

some basic demographics

Let’s start with who Muslim Americans really are. While size estimates of the population range anywhere from 2 million to 8 million, there is general agreement on the social and demographic characteristics of the community.

Muslim Americans are the most ethnically diverse Muslim population in the world, originating from more than 80 countries on four continents. Contrary to popular belief, most are not Arab. Nearly one-third are South Asian, one-third are Arab, one-fifth are U.S.-born black Muslims (mainly converts), and a small but growing number are U.S.-born Anglo and Hispanic converts. Roughly two-thirds are immigrants to the United States, but an increasing segment is second- and third-generation, U.S.-born Americans. The vast majority of immigrants have lived in the United States for 10 or more years.

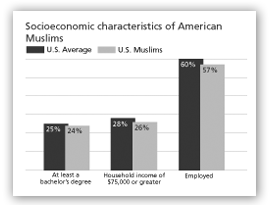

Muslim Americans also tend to be highly educated, politically conscious, and fluent in English, all of which reflects the restrictive immigration policies that limit who gains admission into the United States.  On average, in fact, Muslim Americans share similar socioeconomic characteristics with the general U.S. population: one-fourth has a bachelor’s degree or higher, one-fourth lives in households with incomes of $75,000 per year or more, and the majority are employed. However, some Muslims do live in poverty and have poor English language skills and few resources to improve their situations.

On average, in fact, Muslim Americans share similar socioeconomic characteristics with the general U.S. population: one-fourth has a bachelor’s degree or higher, one-fourth lives in households with incomes of $75,000 per year or more, and the majority are employed. However, some Muslims do live in poverty and have poor English language skills and few resources to improve their situations.

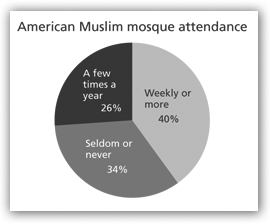

One of the most important and overlooked facts about Muslim Americans is that they are not uniformly religious and devout. Some are religiously devout, some are religiously moderate, and some are non-practicing and secular, basically Muslim in name only, similar to a good proportion of U.S. Christians and Jews. Some attend a mosque on a weekly basis and pray every day, and others don’t engage in either practice. Even among the more religiously devout, there is a sharp distinction between being a good Muslim and being an Islamic extremist.

None of this should be surprising. Many Muslim Americans emigrated from countries in the Middle East (now targeted in the war on terror) in order to practice—or not practice—their religion and politics more freely in the United States.  And their religion is diverse. There is no monolithic Islam that all Muslims adhere to. Just as Christianity has many different theologies, denominations, and sects, so does Islam. And just like Christianity, these theologies, denominations, and sects are often in conflict and disagreement over how to interpret and practice the faith tradition. This diversity mimics other ethnic and immigrant groups in the United States.

And their religion is diverse. There is no monolithic Islam that all Muslims adhere to. Just as Christianity has many different theologies, denominations, and sects, so does Islam. And just like Christianity, these theologies, denominations, and sects are often in conflict and disagreement over how to interpret and practice the faith tradition. This diversity mimics other ethnic and immigrant groups in the United States.

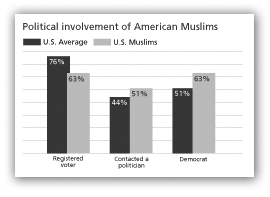

Evidence from the MAPS project, Pew Research Center, and General Social Survey demonstrates that Muslim Americans are much more politically integrated than the common stereotypes imply. Consider some common indicators of political involvement, such as party affiliation, voter registration, and contact with politicians. Compared to the general public, Muslim Americans are slightly less likely to be registered to vote, reflecting the immigrant  composition and voter eligibility of this group (63 percent compared to 76 percent of the general population), slightly more likely to have contacted a politician (51 percent compared to 44 percent of the general population), and slightly more likely to affiliate with the Democratic Party, which falls in line with other racial and ethnic minorities (63 percent compared to 51 percent of the general population).

composition and voter eligibility of this group (63 percent compared to 76 percent of the general population), slightly more likely to have contacted a politician (51 percent compared to 44 percent of the general population), and slightly more likely to affiliate with the Democratic Party, which falls in line with other racial and ethnic minorities (63 percent compared to 51 percent of the general population).

All these data demonstrate that, contrary to fears that Muslim Americans comprise a monolithic minority ill-suited to participation in American democracy, Muslim Americans are actually highly diverse and already politically integrated. They are also in step with the rest of the American public on today’s most divisive political issues.

attitudes, values, and variation

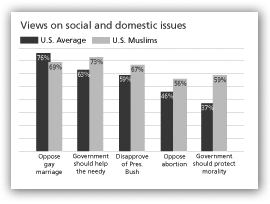

The majority of both Muslim Americans (69 percent) and the general public (76 percent) oppose gay marriage, favor increased federal government spending to help the needy (73 percent and 63 percent, respectively), and disapprove of President George W. Bush’s job performance (67 percent and 59 percent). Muslim Americans are slightly more conservative than the general public when it comes to abortion (56 percent oppose it, compared to 46 percent) as well as the federal government doing more to protect morality in society (59 percent compared to 37 percent).

The one area in which American Muslims are not entirely in step with the general public is foreign policy, especially having to do with the Middle East.  In 2007, for example, the general public was nearly four times as likely to say the war in Iraq was the “right decision” and twice as likely to provide the same response to the war in Afghanistan (61 percent compared to 35 percent of Muslim Americans).

In 2007, for example, the general public was nearly four times as likely to say the war in Iraq was the “right decision” and twice as likely to provide the same response to the war in Afghanistan (61 percent compared to 35 percent of Muslim Americans).

In short, these numbers tell us that Muslim Americans lean to the right on social issues (like most Americans), but to the left on foreign policy. But these generalizations don’t tell the whole story—in particular, these averages don’t demonstrate the diversity that exists within the Muslim population by racial and ethnic group membership, national origin, socioeconomic status, degree of religiosity, or nativity and citizenship status.

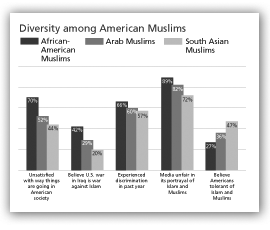

Consider, for example, Muslim Americans’ levels of satisfaction and feelings of inclusion (or exclusion) in American society—major building blocks of a liberal democracy. In examining how these perceptions vary by racial and ethnic group membership within the group, we see that African-American Muslims express more dissatisfaction and feel more excluded from American society than Arab or South Asian Muslims. They’re more likely to feel the United States is fighting a war against Islam, to believe Americans are intolerant of Islam and Muslims, and to have experienced discrimination in the past year (whether racial, religious, or both is unclear). South Asians feel the least marginalized, and Arab Muslims fall in between.  These racial and ethnic differences reflect a host of factors, including the immigrant composition and higher socio-economic status of the South Asian and Arab populations and the long-standing racialized and marginalized position of African Americans. Indeed, many (though not all) African Americans converted to Islam seeking a form of religious inclusion they felt lacking in the largely white Judeo-Christian traditions.

These racial and ethnic differences reflect a host of factors, including the immigrant composition and higher socio-economic status of the South Asian and Arab populations and the long-standing racialized and marginalized position of African Americans. Indeed, many (though not all) African Americans converted to Islam seeking a form of religious inclusion they felt lacking in the largely white Judeo-Christian traditions.

(Incidentally, most African-American Muslims adhere to mainstream Islam [Sunni or Shi’a], similar to South Asian and Arab Muslim populations. They should not be confused with the Nation of Islam, a group that became popular during the civil rights era by providing a cultural identity that separated black Americans from mainstream Christianity. Indigenous Muslims have historically distanced themselves from the Nation of Islam in order to establish organizations that focus more on cultural and religious [rather than racial] oppression.)

Before we can determine whether religion is the driving force behind all Muslims’ political opinions and behaviors—whether Islam, as is popularly assumed, trumps Muslim Americans’ other commitments and relationships to nationality, ethnicity, race, and even democracy—let’s step back and place Muslim Americans in a broader historical context of religion and American politics.

when religion matters, and doesn’t

Muslim Americans aren’t the first religious or ethnic group considered a threat to America’s religious and cultural unity. At the turn of the 20th century, Jewish and Italian immigrants were vilified in the mainstream as racially inferior to other Americans. Of course today those same fears have been projected onto Hispanic, Asian, and Middle Eastern immigrants. The Muslim American case shares with these other immigrant experiences the fact that with a religion different from the mainstream comes the fear that it will dilute, possibly even sabotage, America’s thriving religious landscape.

Yes, thriving. By all accounts, the United States is considerably more religious than any of its economically developed Western counterparts. In 2000, 93 percent of Americans said they believed in God or a universal spirit, 86 percent claimed affiliation with a specific religious denomination, and 67 percent reported membership in a church or synagogue. The vast majority of American adults identify themselves as Christian (56 percent Protestant and 25 percent Catholic), with Judaism claiming the second largest group of adherents (2 percent), giving America a decidedly Judeo-Christian face. There are an infinite number of denominations within these broad categories, ranging from the ultra-conservative to the ultra-liberal. And there is extensive diversity among individuals in their levels of religiosity within any given denomination, again ranging from those who are devout, practicing believers to those who are secular and non-practicing.

This diversity has sparked extensive debates among academics, policy-makers, and pundits over whether American politics is characterized by “culture wars,” best summarized as the belief that Americans are polarized into two camps, one conservative and one liberal, on moral and ethical issues such as abortion and gay rights. Nowhere has the debate played out more vividly than the arena of religion and politics, where religiously based mobilization efforts by the Christian right helped defeat liberal-leaning candidates and secure President Bush’s reelection in 2004. Electoral victories, however, haven’t usually translated into policy victories, as evidenced by the continued legality of abortion and increasing protection of gay rights. So when does religion matter for politics and when doesn’t it?

Here we come back to the Muslim American case. Like Muslim Americans, Americans generally have multiple, competing identities that shape their political attitudes and behaviors—93 percent of Americans may believe in God or a universal spirit but 93 percent of Americans don’t base their politics on that belief alone. In other words, just because most Americans are religiously affiliated doesn’t mean most Americans base their politics on religion.  To put it somewhat differently, the same factors that influence other Americans’ attitudes and behaviors influence Muslim Americans’ attitudes and behaviors. Those who are more educated, have higher incomes, higher levels of group consciousness, and who feel more marginalized from mainstream society are more politically active than those without these characteristics. Similar to other Americans, these are individuals who feel they have more at stake in political outcomes, and thus are more motivated to try to influence such outcomes.

To put it somewhat differently, the same factors that influence other Americans’ attitudes and behaviors influence Muslim Americans’ attitudes and behaviors. Those who are more educated, have higher incomes, higher levels of group consciousness, and who feel more marginalized from mainstream society are more politically active than those without these characteristics. Similar to other Americans, these are individuals who feel they have more at stake in political outcomes, and thus are more motivated to try to influence such outcomes.

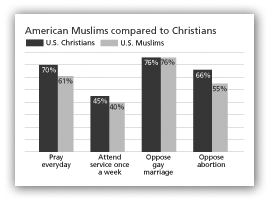

Muslims, on average, look like other Americans on social and domestic policies because, on average, they share the same social standing as other Americans, and on average, they are about as religious as other Americans. Consider two common indicators of religiosity, frequency of prayer and frequency of church attendance, and compare Muslim Americans to Christian Americans. Both groups are quite religious, with the majority praying everyday (70 percent of Christians compared to 61 percent of Muslims) and a sizeable proportion attending services once a week or more (45 percent compared to 40 percent). And they look similar with respect to attitudes on gay rights and abortion, in part because Christian and Muslim theology take similar stances on procreation and gender roles.

Again, these numbers tell only part of the story. What’s missing is that religion’s relationship to politics is multidimensional. In more complex analyses it has become clear that the more personal dimensions of religious identity—or being a devout Muslim who prays everyday—have little influence on political attitudes or behaviors, which runs counter to stereotypes that link Islamic devotion to political fanaticism.

In contrast, the more organized dimensions of Muslim identity, namely frequent mosque attendance, provide a collective identity that stimulates political activity. This is similar to what we know about the role of the church and synagogue for U.S. Christians and Jews. Congregations provide a collective environment that heightens group consciousness and awareness of issues that need to be addressed through political mobilization. Thus, it is somewhat ironic that one of the staunchest defenders of the war on terror—the Christian right—may be overlooking a potential ally in the culture wars—devout Muslim Americans.

an exceptional experience

In many ways these findings track closely with what we know about the religion-politics connection among other U.S. ethnic and religious groups, be they Evangelical Christians or African Americans. They also suggest that the Muslim experience may be less distinct than popular beliefs imply. In fact, Muslim Americans share much in common with earlier immigrant groups who were considered inassimilable even though they held mainstream American values (think Italian, Irish, and Polish immigrants).

At the same time, though, we can’t deny that the Muslim American experience, particularly since 9/11, has been “exceptional” in a country marked by a declining salience of religious boundaries and increasing acceptance of religious difference. Muslim Americans have largely been excluded from this ecumenical trend. If we’re going to face our nation’s challenges in a truly democratic way, we need to move past the fear that Muslim Americans are un-American so we can bring them into the national dialogue.

further reading

read more about jen’nan read’s research

- How will Muslim vote this year?: an op-ed piece by Read on Muslim American voting.

- The Truth About Muslism: LiveScience discusses Read’s work.

Pew Center Data

Looking for more good scientific data on US Muslims? Then check out the Pew Center Report on Muslim Americans that Read draws on in her article.

30 Days with Muslim Americans

Read’s article raises the question of what it’s really like to be both Muslim and American in a post-9/11 environment. In this episode of Morgan Spurlock’s TV show “30 days,” a conservative Christian finds out as he agrees to live as a Muslim for thirty days, learning a lot about both the differences and similarities between himself and Americans who practice a different faith:

(Watch the video full-screen on hulu.com.)

Muslim Americans and American Culture

While it is widely believed that Muslim Americans are not well integrated into mainstream American culture, Read’s findings demonstrate these beliefs are mistaken. In fact, you may be surprised at all the places you can find Muslim Americans in popular culture – in hip-hop, country music, and even in the fashion industry.

And if you’re interested in a more artistic approach to the everyday lives of Muslim Americans, Muslim American photographer Ahmed Bashir has a nice collection of photos at his website.

recommended books and articles

Anny Bakalian and Mehdi Bozorgmehr. Backlash 9/11: Middle Eastern and Muslim Americans Respond (University of California Press, 2009). One of the comprehensive assessments of the experiences of Middle Eastern Americans in the aftermath of 9/11.

Clem Brooks and Jeff Manza. “Social Cleavages and Political Alignments: U.S. Presidential Elections, 1960 to 1992,” American Sociological Review (1997) 62: 934–946. A sociological framework for understanding how social group memberships, such as gender and race, impact Americans in presidential elections.

Nancy Foner. In a New Land: A Comparative View of Immigration (New York University Press, 2005). A thorough historical, comparative account of immigration in the United States.

Gary Gerstle and John Mollenkopf, eds. E Pluribus Unum? Contemporary and Historical Perspectives on Immigrant Political Incorporation (Russell Sage Foundation, 2001). This edited volume places contemporary immigration politics in historical and comparative context.

Ted J. Jelen. “Religion and Politics in the United States: Persistence, limitations, and the prophetic voice,” Social Compass (2006) 53: 329–343. A useful overview of the U.S. religion-politics connection situated in comparison to other western, industrialized nations.

Comments 7

Docuticker » Blog Archive » Muslims in America

November 11, 2008[...] Muslims in America Source: Contexts Magazine/American Sociological Association Seven years after the terrorist attacks on U.S. soil catapulted Muslims into the American spotlight, concerns and fears over their presence and assimilation remain at an all-time high. [...]

Attitudes Toward Muslims in America « Rhapsodyinbooks’s Weblog

November 12, 2008[...] Read the entire article, with data on Muslim attitudes, values, and variations, here. [...]

Immigrant facts and furphies « A possie in Aussie

February 2, 2009[...] don’t have time to research the facts in Denmark, but here is a research-based article that explodes similar myths about Muslims in America – and I can’t imagine that Muslims in [...]

Imiigration facts and furphies « A possie in Aussie

February 2, 2009[...] don’t have time to research the facts in Denmark, but here is a research-based article that explodes similar myths about Muslims in America - and I can’t imagine that Muslims in Denmark are hugely [...]

Contexts Magazine » From the Editors

May 19, 2009[...] in these pages last spring. We were similarly gratified to see media using Jen’an Read’s contribution to our fall issue to help inform public understandings of Muslims in America. And we don’t think it was [...]

zcato

May 6, 2010I'm sick of people being so against Islam when they don't even know that much about it. If we're ever going to view ourselves as a progressive society, we need to realize the differences in every group, and that no identity that we impose is ever a whole identity for any one person. Ever since the attacks on the towers, the wave of open hate against Islam has been astounding, not only in magnitude, but also because it seems so justified in the eyes of many.

What I also find amazing is the belief that the religion of Islam is so different from the dominant religion in the US, Christianity, when they come from very similar texts. Hopefully our society as a whole will be able to move past these prejudices and back to a state of well-being and coexistence.