A 2018 Nike ad featuring Kaepernick.

Taking a Knee

Colin Kaepernick started one of the most visible protests for social justice in modern sports history. He gathered the attention of fans and non-fans alike, now sitting—or kneeling—at the center of a major political controversy. Kaepernick is no longer in the NFL, yet his name remains attached to what have been called the “Take a Knee” protests against systematic racism and the treatment of minorities in the U.S. (including their deaths at the hands of police and their disproportionate incarceration rates). His effort, and its backlash, echoes the iconic “Black Power Salute” offered by American runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the Olympic podium after medaling in the 200-meter race in the 1968 Summer Games.

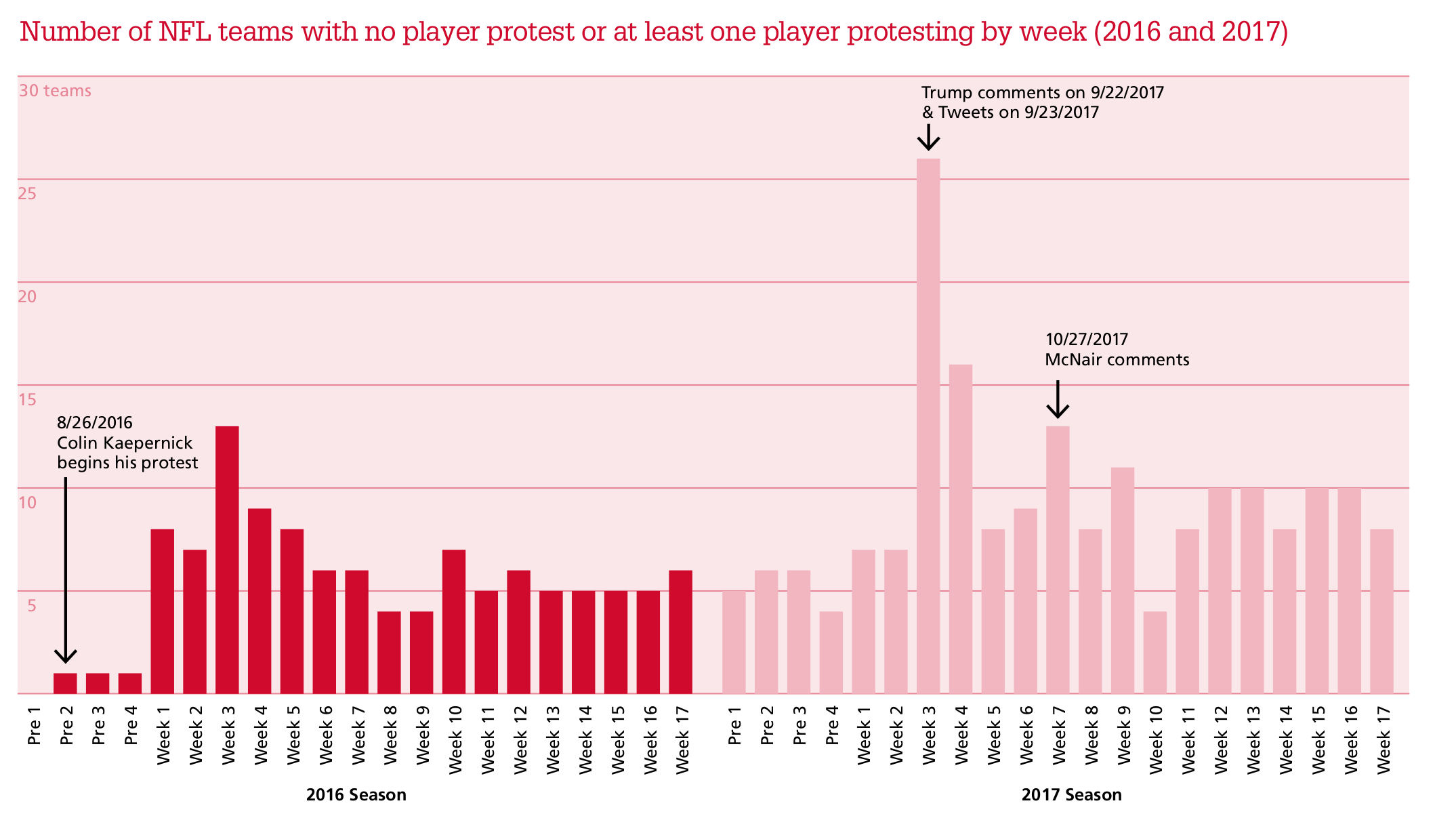

Despite the political controversy and attention devoted to the players’ protest, our analysis of two full seasons worth of data show that protests during the national anthem were smaller than the media coverage suggested. Only a small percentage of players protest on any given week, and several teams had no protesting players at all. When we examined what led to participation among players, we found that specific national events increased the number of player protests, especially when it seemed that efforts were being made to discredit protesting players.

We built a dataset from ESPN.com’s reporting and running lists of players en-gaged in protest. We validated ESPN.com’s reporting by examining counts of protests on sites such as BleacherReport.com and SBNation.com and in local news coverage. “Player protest” was classified as any player doing any of the following before, during, or after the national anthem as an act of protest: sitting on a bench, kneeling, raising a fist in the air, choosing to stay in the locker room (stated as a protest), or staying in the “tunnel” (stated as a protest). We did not include in our data set more passive actions such as: placing a hand on another player, placing an arm around another player, or wearing a “unity” shirt during warmups. These passive actions usually demonstrated support or solidarity with teammates rather than a commitment to protesting on issues of social justice.

As a final measure, we consulted media pictures of the sidelines to identify protestors. When depictions of protests did not include specific counts but said “most” players (for example, “most of the New Orleans Saints knelt during the anthem”) and no game-day photographs existed, we counted half the active roster +1 as protesting. Since teams can have 46 players dress in uniforms, we counted “most” as 24 players.

Only a handful of teams beyond Kaepernick and his San Francisco 49ers teammates participated in protests during the 2016 season. No more than 36 players protested in any week. With almost 1,500 NFL players suiting up in a week, this meant that no more than 2.5% of players protested in any given week during the 2016 season. On 15 of the 32 NFL teams, not a single player engaged in any protest during 2016. We counted only 291 instances of protest during the entire 2016 season.

Kaepernick was released by the San Francisco 49s between the 2016 and 2017 seasons and has yet to be signed by another team. The relatively small number of protests at the beginning of the 2017 season suggests the protests were losing steam.

Then, in the third week of the 2017 season, Donald Trump stepped into the fray. During a campaign speech for U.S. Senate candidate Luther Strange, Trump bellowed, in reference to NFL player protesters, “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired. He’s fired!” Trump’s speech and the tweets that followed gave new energy to the Take a Knee movement. That weekend, 405 players across 26 (of 32) teams protested. More players protested that week than in all the earlier protests combined.

Despite the show of solidarity involving almost a quarter of the players, the number of protests fell to 213 players the next week. In the fifth week of the season, a week and a half after the president commented on the protests, only 37 players protested, and approximately the same number (41) protested in Week 7.

The lull was temporary. Before games during Week 7, news leaked that Bob McNair, the owner of the Houston Texans, had told other owners in a meeting “we can’t have the inmates running the prison.” This infuriated many players for two reasons. First, because the players were protesting inequality in the criminal justice system, and second, these racist comments were coming from a White owner talking about the NFL’s predominantly African-American player pool.

McNair’s comments led to a small upsurge in protests during Week 7. Fifty-seven players on 13 teams protested that week. The weeks following had relatively stable protest levels until the last week of the season.

The statements made by the president and McNair increased protests because they attempted to demean and discredited the players. The comments further stigmatized players, reframing the act of kneeling or raising a fist as dishonorable conduct rather than nonviolent protest. Fans, however, had already been stigmatizing players, ever since Kaepernick’s initial act of sitting on the bench in preseason Week 2 of 2016. Trump was just trying to tap into that fan sentiment, while being targeted by Trump moved players to solidify their position against the stigmatization. In line with sociological literature, we see how stigma can be used against a group or organization as a means of social control—and how it can mobilize the stigmatized population.

Rather than isolating the few players protesting, protests became more widespread after the comments by Trump and McNair. Eight-five percent of the league’s teams had at least one player protest in this period. Intra-organizational dynamics seemed to be at play, too. Despite having no protests in 2016, the New Orleans Saints had, by far, the most players protesting in 2017. Only one player on the Seattle Seahawks had protested in 2016, but the team would see the second most protests in the league in 2017. The San Francisco 49ers, Kaepernick’s former team, followed at third in 2017.

The focus of the protests on racial inequality and social justice becomes more apparent when we consider the five teams that saw no players protest in 2017: the Arizona Cardinals, New York Jets, Chicago Bears, Minnesota Vikings, and Cincinnati Bengals. Given that Kaepernick’s focus included police violence against young Black men, those last three teams are surprising. During these two years, Chicago was dealing with the aftermath of the Laquan McDonald shooting, Minnesota’s Twin Cities experienced the shooting of Philando Castile, and Cincinnati was dealing with a series of mistrials in the shooting of Samuel DuBose. Major public demonstrations in these cities did not spill onto the football field.

This past May, the NFL owners passed a new rule that will require all players on the field during the national anthem to stand. However, players can choose to stay in the locker room rather than be on the field. Players can not take a knee, or perform any sort of visible protest anymore. And rather than fining individual players for protest, in the 2018 season, teams will be fined for violations. Christopher Johnson, who is running the New York Jets, suggested that he would not pass on team fines to individual players, despite the fact none of his players engaged in protest in 2016 or 2017.

Some players are reportedly considering stopping their protests. This is in part because of an agreement between the Players Coalition and NFL owners to spend $90 million toward social justice issues at the local level, showing that the protests were nominally effective. But, players could also be rethinking their stance as protestors because, as of July 6th, 2018, Kaepernick and 49er teammate and fellow protester Eric Reid remain unsigned. These players have filed lawsuits alleging collusion by the NFL to “blackball” them as early protestors, keeping them from employment. And much like Smith and Carlos following their protests 50 years ago, Kaepernick and Reid find themselves on the right side of the argument, but on the wrong side of unemployment.

Comments 2

sandra

November 26, 2018The third chart is unclear, "...teams with no player or at least on player..." would equal all teams?

Your son

January 6, 2019Please stop mama