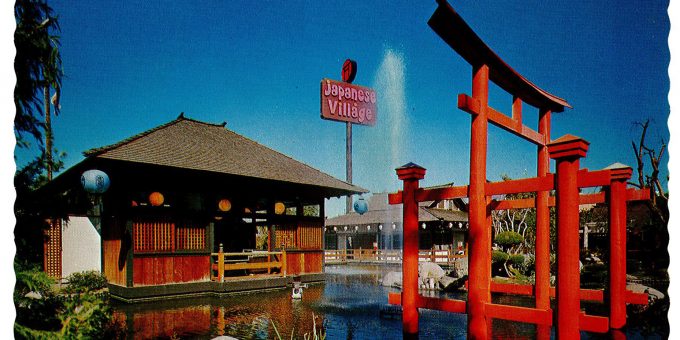

Japanese Village and Deer Park circa 1972. Author courtesy.

Playing Foreign and Building Community at Deer Park

Japanese Village and Deer Park operated from 1967-74 as part of the growing Orange County, CA amusement corridor, anchored by Disneyland. “Deer Park,” as it is affectionately remembered by former employees, was the brain child of Allen Parkinson, a White entrepreneur who proclaimed it “America’s only authentic Japanese village.” To create this “authentic” Japanese experience for predominantly White visitors, the park mainly hired third-generation Japanese American youth—sansei, the grandchildren of Japanese immigrants. However, these sansei came from the surrounding middle-class suburbs, lacked familiarity with Japanese culture, and were active in school and community institutions—sociological hallmarks of integration. Why would such well-integrated youth flock to an employment opportunity centered on a culture foreign to them? Community and a sense of belonging.

By bringing together the façade of Japan, local sansei employees, and White patrons, Deer Park highlights how otherwise integrated Japanese Americans continued to be racially othered and marginalized in the late 20th century United States. In other words, sociological assumptions of integration across time and generations fall short in explaining the trajectories of Japanese Americans as people of color. Their experiences show that full integration cannot be defined by class status or residential desegregation alone, but must also include a more nuanced racialized understanding of belonging and recognized membership in the larger community. Deer Park’s strategy of visual authenticity also enhanced the personal feelings and external perceptions of sansei youth as “forever foreigners” in their own backyard, but did not negate the inherent Americanness of sansei employees. Based on 41 interviews with former sansei employees—now in their 60s and 70s—as well as 404 personal photographs and promotional materials from Deer Park, I examine how sansei employees negotiated the fulfillment of foreign fantasy by “playing” Japanese even as they forged a local sense of belonging and built community.

At Deer Park, sansei employees portrayed Japanese villagers, wearing Japanese garb during their mundane interactions with park guests in souvenir shops, petting zoos, and eateries. Former employees describe being hired on the spot for their Japanese surnames and appearance. Cynthia recalls her hiring interview, noting management did not seem to care that she didn’t speak any Japanese and was unfamiliar with Japanese cultural practices. Cynthia—like other female employees—was required to wear a kimono, but she was unaware of the traditional way to put on the ornate garment. In another worker’s particularly poignant memory, management instructed, “Don’t speak, because we want the illusion that you’re from Japan.”

Employees were supposed to abide by dress codes that underscored their foreign racialization. In addition to the women in kimonos, most men wore happi coats—a waist-length, straight-sleeved coat usually worn by house servants or during festivals. Former employees, Brenda and Jack, discussed how these policies set them up as consumable objects of ethnic and racial “otherness.”

Brenda: They [patrons] probably thought we were from Japan, even though we spoke perfect English.

Jack: We were probably just as Americanized as they were, I think sometimes they did approach me and go, “Do you speak English?”

Brenda: I don’t think they saw us as Americans. They saw us as…

Jack: Part of the landscape.

Brenda: People from Japan, imported to work…You didn’t have to play a part, you just…

Jack: You just have to look the part.

Along with employee recollections, Deer Park’s promotional photographs confirm that employees were “part of the landscape.” They were utilized as models in brochures, advertisements, and postcard images of the park, but rarely as the focal point. Employees were pictured as ornamental features, inseparable from the built environment. As Jack and Brenda noted, this relationship made employees feel simultaneously exposed as foreign props and invisible as local American youth. Growing up in the Southern California suburbs, sansei employees would seem integrated in socioeconomic terms. Nonetheless, their racial otherness and lack of recognized belonging persisted. Park guests did not recognize employees as U.S.-born local kids.

While promotional photos intended to accentuate the Japanese authenticity of the space and employees of Deer Park, they also betrayed employees’ American identities. As Lisa reminds us, “in our real lives, we [sansei] grew up with all those people [in LA and Orange counties] anyways.” In their everyday lives and as employees in the park, sansei mimicked the fashion and trends from the same popular culture consumed by their White peers. Men, for example, often sported shaggy, long hair as seen on popular 1960s television shows like Laugh In and The Partridge Family. Women wore elaborate, fashionable up-dos, simple make-up, and long eyelashes, mirroring the contemporary fashion trends from the pages of Tiger Beat and Seventeen magazines. Even the kimonos drew from the contemporary popularity of vibrant color palettes rather than the more traditional red and indigo dye tones used in traditional silk kimonos. These American cultural markers were largely invisible to park patrons. Under the hair and behind the make-up remained a Japanese, and ultimately foreign, face.

If American cultural markers were invisible to White patrons, they did not go unnoticed among sansei employees. Within the space of Deer Park, sansei employees demonstrated and claimed their belonging within the local community and broader American cultural imaginary through visible fashion choices. The coded displays of popular American cultural markers helped sansei recognize other individuals with similar interests. Sansei employees spoke about how Deer Park was their first time interacting with a critical mass of “cool” sansei with a diverse set of interests and personalities. Donna, another former employee, remembers, “Deer Park was a chance to meet Japanese Americans… all different kinds of Japanese with different backgrounds and everything and a big group of them. In high school, there were like maybe three Japanese boys, and that wasn’t really a good experience, because they were not cool. But at Deer Park, there was such a broad range of them.”

Beyond finding common interests, sansei found deeper connections in their shared experiences of racism and racial marginalization. Most were active participants in their home communities and generally felt well integrated, but they often recalled a lingering sense of being distinct from their White peers. Again, Brenda and Jack:

Jack: It’s amazing how similar everybody was [at Deer Park]. The way they think and how they acted. So, you kind of fit in really easily.

Brenda: I mean, our backgrounds are the same. Our parents kind of all have similar experiences. You know, the war and the prejudice. Even now, we met another Japanese couple where we play golf and it’s just… A camaraderie, huh?

Jack: You just feel actually comfortable with people.

Brenda: You know, with hakujins (White people), it’s just a little bit of a—

Jack: They’re different. I mean you don’t realize they’re different until you meet a lot of Japanese people and then think, “Oh my gosh! They’re like me!”

Brenda: Yeah, I mean there were certain times growing up and just feeling a little bit the odd ball out… an odd feeling. So once you get to [Deer Park], it’s like, oh you weren’t odd at all. It’s just, it’s because you’re Japanese, you know. You didn’t realize that you felt this way.

As Brenda and Jack interacted with other Japanese Americans at Deer Park, they learned that their experiences of racial marginalization were not unique. Sanseis’ common experiences of racism laid a foundation for building their own sense of local belonging. They recognized each other’s experiences of racial marginalization as particularly local, American experiences and markers of community membership.

The marginalization felt by sansei in their neighborhoods and schools reveals their unfulfilled integration due to race, even amid markers of upward mobility. Sansei actively sought out Deer Park—and the critical mass of Japanese American youth it attracted—where there was a local community in which their belonging and membership would be readily recognized. Ethnicity and race play a central role in the creation of community and belonging for Japanese Americans thereby shaping their integration experience. This is an important reorientation in understanding the integration process and provides greater insight into the persistent, entrenched, and insidious impact of race on that process—not just for Japanese American, but for communities of color more broadly. Importantly, while sansei proactively asserted their own terms of belonging and recognized membership at Deer Park, their integration remained incomplete. They continued to be racially marginalized as foreign and have their membership go unrecognized in broader society. Eminent race scholar Patricia Hill Collins notes that, given persistent experiences as the “outsider within,” communities of belonging based in ethnicity remain foundational for people of color as they cope with marginalization and claim membership within their local and national communities. As Denise shared, “At Deer Park, I felt like it was okay to be Japanese. I think I would’ve grown up wishing I was hakujin (a White person) if I did that differently… It was just like a utopia for sanseis.”