Race, Displacement, and the Public Intellectual: An Interview with Viet Thanh Nguyen

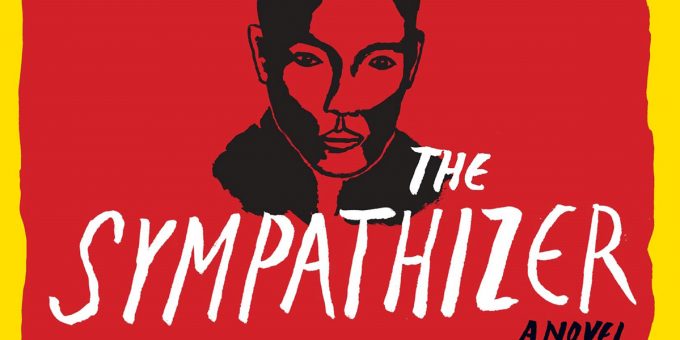

Viet Thanh Nguyen is a Vietnamese American novelist and academic whose books include The Refugees, Nothing Ever Dies, Race and Resistance, and a new edited collection, The Displaced, alongside his best-selling, Pulitzer Prize winning book The Sympathizer. Nguyen, University Professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California, sat down with Contexts’ guest editor Anthony Ocampo to discuss intellectual worlds—and what it means to grapple with race and displacement in, through, and across those spaces.

Anthony Ocampo (AO): I know you have a background in English as well as ethnic studies. I was wondering if you could share how these two intellectual spaces have shaped who you are as a professor and as a writer.

Viet Thanh Nguyen (VTN): I started off as an English major because I loved reading. I love literature, and that was always my first love since I was a little boy. Literature had sustained me through a lonely childhood, and I derived a lot of pleasure in it. When I came to college, that was the major I chose.

I never thought that I could do anything with that degree after graduation except perhaps become a lawyer. I had no idea what it meant to be a professor or a teacher. Neither of those were goals I had. But it was ethnic studies—taking courses in Asian American Studies, but also in African American Studies, Chicano Studies—that convinced me that intellectual inquiry could be related to political inquiry.That gave me a sense of self-justification with which I could go to my parents and everybody else and say, “Look, this work that I’m doing with books really matters outside the world of books.” Eventually, I also wanted to write my own books, as a scholar and as a fiction writer. Those were things that would evolve over time.

AO: One of the things most impactful [in] your work is this unapologetic centering of the Vietnamese refugee experience as a way to re-tell major historical events. How did you start thinking about The Sympathizer, Nothing Ever Dies, and The Refugees?

VTN: The last three books have been the culmination of many aspects of my life’s concerns. It’s not that I wasn’t always curious about my parents, being Vietnamese, and the history of the Vietnam War. That developed around the same time I wrote about what it meant to be Asian American. When I was an undergraduate, I wrote two senior theses: one on Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, and one on Vietnamese literature.

When I got to graduate school, my ambition… was to write a dissertation on Vietnamese American literature and the Vietnam War. During my orientation meeting with the department chair, he told me, “You can’t do this. You’re not going to get a job.” This was 1992.

I was very pragmatic. I’m a refugee, I’m a son of refugees—it was a lot to go to graduate school, and I wasn’t about to do it without getting a job. So I said, “This might not be a viable career choice at this moment.” I started doing Asian American literature, which was the right career choice.When I finished my first book on Asian American literature, I started to go back to the Vietnam projects and my desire to write fiction, which I put on the backburner for the decade I was in graduate school and an assistant professor.

While I never stopped thinking about the Vietnam War, Vietnamese history, and being Vietnamese, I had, consciously or unconsciously, not grappled with what all those things meant for me emotionally. I grappled with what they meant intellectually, but I think in order to become a writer—among other things I had to do, like learn how to write—I also had to place myself in a personal, emotional history. And that is always part of learning how to write, too. That’s why I think it took so long for me to get around to writing and finishing these three books. There were so many disciplinary and artistic things to learn, but I also had a lot of emotional things to learn. If you are a Marxist, like I am, you believe everything is connected.

AO: You went to graduate school in the early ‘90s, and now there’s this new generation of scholars who are going about their academic careers very differently. They do what they need to do to get their PhDs, but they’re also doing things like publishing op-eds and producing creative pieces. They’re becoming influential on Twitter. What are your thoughts on this new model?

VTN: I think this is a combination of both the reality of the job market and accessibility of new platforms. In 1992, when I started graduate school, we knew the market was not great, but I don’t think there was that same sense of desperation that might be around today. I think many of [today’s graduate students] are having to develop a different kind of practice outside of the academic one, because their chances of landing a job where they can practice the most conventional skills is really limited. If, in 1992, things like Facebook and Twitter existed, I would have been on those. The moment email became readily available in the ‘90s, I got on that. You actually had to know a bit of code to be connected to your email.

It became normal for professors and graduate students to utilize platforms such as blogging, because it allow[ed] them to get outside of the traditional gatekeeping of publication. Who in their right minds would want to wait a year or two years or longer to get an article published? It can be frustrating. When it became easy to publish your own blog, I did that in something called Diacritics (diacritics.org), both as my own vehicle, but also as a vehicle for other Vietnamese writers. That was enormously important to me, because it allowed me to have a certain kind of activism by creating this platform, posting other writers, and promoting them. But also because it was free from all kinds of academic constraints.

I wrote a lot of little pieces for that blog in which I would share theoretical and critical ideas, but couch them in everyday language, using humor and satire—[it] allowed me to exercise and experiment… without penalty (except pushback from irate readers). That was really critical to The Sympathizer… a comic novel… and, when it came time for me to write things for The New York Times, I was ready….

That’s what these graduate students are doing… getting the practice of being public intellectuals… writing for multiple audiences.

AO: You talk about how your books took so many years to write. There’s a lot of merit to letting ideas and writing and thoughts ferment. But, as you mentioned, there’s this importance of being responsive when movements around the refugee crisis or #BlackLivesMatter [are happening]. How do you negotiate what type of writing you’re going to do?

VTN: I think all my decisions are strategic, so I would never advise someone to let a project ferment if there was a present deadline they had to meet like tenure. I wrote my first academic book (Race and Resistance with Oxford University Press) as fast as I possibly could because I needed to make tenure. I’m not incredibly satisfied with the first book, but it gave me a career, and that’s part of the strategy, you know? We always have to be strategic about our survival. There always has to be a calculation of, “When can I take a stand? When can I take a risk? When do I have to play it safe?” Now those people [who] always play it safe and never take a stand—that can present a real problem, because those people are not allies. Most of them are enemies.

Once I got tenure, I was like, “Okay, I’m going to do exactly what I want to do.” …If they can’t fire you, then you should do what you want to do. [So] when I got tenure, I became a fiction writer, and I embarked on a second academic book that took 14 years. And that was really challenging. Because I wanted to publish another academic book a lot faster. I wanted to become a full professor. But the nature of the project demanded that I take 14 years. That [for me] was taking a stand, and even though it was a very long “stand,” you do what you believe in intellectually.

Today, that issue [of devoting time to a long term project or to an op-ed] is a question I wrestle with…. I thought that, “I had just won the Pulitzer Prize, I don’t know how long this window is going to be open where everyone is asking for me, so I am going to take advantage of it and get my perspective out there in this world of punditry and all that stuff.” …I have opportunities to take a platform that is about ethnic studies, that is about postcolonial critique, that is about minority discourse to The New York Times or whatever…. [I]n the year after the Pulitzer Prize, I wrote little fiction, but I wrote a whole bunch of op-eds.

That’s not something I would do every year of my life, but… that was the right decision. It gave me a certain visibility. …I can pick and choose when I want to say something in an op-ed and allow myself more time to go back to my novel—which is what most people want from me, and is what I want for me anyway.