Reproducing the Nation

My grandmother gave birth to nine children starting at age 16.

My mother delivered the first of her three babies at 27. I gave birth to my only child when I was 32. Prime Minister Erdoğan believes I am not doing my duty as a Turkish citizen.

“Have at least three children,” Erdoğan regularly exhorts audiences. “It is easier these days since the economy is doing well.” But, today, at a time of high unemployment rates, stagnant real wages, job insecurity, and soaring school expenses, most Turks find it difficult to raise three children.

Erdoğan boasts that his wife washed their four children’s diapers by hand. It is women’s job to raise children, he implies.

He argues that raising children is “easy these days.” On a recent visit to Kazakhstan, looking at that country’s vast land base, he advised each family to have five children.

Speaking at a population conference, he declared that abortion is murder.

Many doctors are highly critical of such claims, and of the prime minister’s politicization of reproductive health and rights.

So are feminists. Maternal mortality rates will go up, they counter, if abortion is criminalized. The state should reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies, they say, instead of instituting bans. But Erdoğan an is unmoved.

“We are preparing the abortion legislation, and we will pass it,” he declared recently. Erdoğan drew a troubling analogy, too, between abortion and the Turkish Army’s December 2011 killing of 34 Turkish Kurds—all civilians, half of them children—in Uludere, on the Iraqi border. He said, “There is no difference between killing a child in her mother’s womb, and killing him outside.”

Erdoğan has also politicized Caesarean births, arguing that Turkey has more Caesarians than similar countries, and that the procedure lowers the nation’s population growth rate. Curtailing the use of unnecessary Caesarians can promote women’s (and babies’) well-being—thus the relatively small outcry against his comments on Caesarians—but Erdoğan’s argument against the procedure rests on the mistaken notion that multiple C-sections render a woman incapable of further births.

Claiming that current trends will push Turkey’s population into decline by 2037, Erdoğan suggests that Caesarian births and abortions are part of a “conspiracy to wipe this nation from the world stage.” But people want fewer children (than the current average of 2.7 per rural, and 2 per urban, household). It is this trend that most concerns him.

Lie Back and Think of Turkey

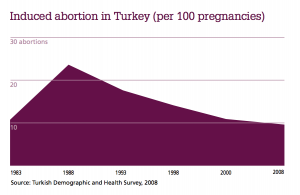

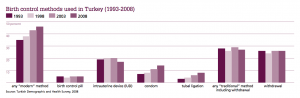

No demonstrable increase in the numbers of abortions occurred to spark this novel politicization of abortion in Turkey. Abortion rates increased in the decade following the legalization of elective abortions in 1983, but began a steady decline in the mid-1990s due to increased access to healthcare, and affordable contraceptives.

The move to ban abortion in Turkey is part of an effort to manage the population by disciplining women’s fertility. It is indicative of a new “reproductive governmentality” that works across borders to limit reproductive choice—a “choice” that is always constrained by economic and cultural realities. It highlights the vulnerability of women’s reproductive rights and well-being even in the formally democratic and relatively progressive Turkey. To the extent that Erdoğan and his conservative government are considered a model for the transitioning Arab countries, their discourse and policies do not bode well for the future of women’s reproductive health and rights in the region.

The move to ban abortion in Turkey is part of an effort to manage the population by disciplining women’s fertility. It is indicative of a new “reproductive governmentality” that works across borders to limit reproductive choice—a “choice” that is always constrained by economic and cultural realities. It highlights the vulnerability of women’s reproductive rights and well-being even in the formally democratic and relatively progressive Turkey. To the extent that Erdoğan and his conservative government are considered a model for the transitioning Arab countries, their discourse and policies do not bode well for the future of women’s reproductive health and rights in the region.

Throughout the world, women’s bodies and fertility have long been a matter of public policy. In the United States and Europe women’s reproductive rights have been defended in relation to the right to privacy, respect for religious diversity, and a woman’s right to choose.

In Turkey, by contrast, the debate over abortion has historically been framed as a population issue. Modern contraceptives were made available in 1965 and elective abortions in 1983, following the diffusion of population control models as a means to industrial development in the Third World.

From the 1920s until the 1960s, Turkey encouraged childbearing in the service of nation-building and agricultural development. Pro-natalist policies tried to reverse population decline following a decade of war. The 1936 Turkish Criminal Code classified abortion as a “crime against the unity and health of the race,” illustrating the subjugation of women’s reproductive choice to the nationalist project in this period.

Representations of ideal motherhood were selectively incorporated into nationalist discourses, as the tragic story of “Sister Serife” illustrates. As national myth has it, a young Turkish woman, from a small Black Sea village, helped the war effort by transporting ammunition. Placing her baby girl in an ox-drawn ammunition cart, and covering both with the only blanket she had, Serife froze to death after an all-night journey on foot.

Turkish officers found the crying baby under her mother’s dead body the next morning. It is said that the officers handed the orphaned baby to a woman nearby who nursed and raised her. In other versions of the story, a military commander’s wife adopted her. It is also possible that the baby—like her mother, and like many children in war zones today—died.

After sacrificing their lives and babies to carry ammunition to the front during the Turkish War of Liberation of 1919-22, in the subsequent phase of nation-building women were expected to replenish the population. Pro-natalism, arose out of the need for labor power in this largely agricultural society, and included a ban on importing contraceptives, free obstetrical care, tax policies favoring larger families, and lower legal age of marriage.

Even more telling perhaps, is the fact that certificates and medals were awarded to women who had given birth to six children.

Turkey’s pro-natalist policies, together with improvements in agricultural production, health, education, and life expectancy, led to population growth just as “population control” was emerging as a hegemonic idea on the world stage.

From Pro-Natalism to Population Control

In the 1950s and 60s, fearing that population growth might destabilize economically “underdeveloped” countries and create a “breeding ground” for communism, powerful states, international organizations and state agencies began to promote anti-natalist state policies around the world. Social scientists and health professionals busily surveyed fertility rates and family planning practices, promoting population control technologies to Third World governments and state agencies. Curtailing women’s fertility, they believed, would facilitate industrial development.

As U.S. aid agencies and the U.N. Population Fund—half of whose initial funding came from the United States—promoted population control as a national development strategy in the 1960s, Turkey turned away from pro-natalist policies, lifting the ban on imports of contraceptives, and promoting family planning nationally.

The dominance of the ideal of modernization, which promoted industrialization and Westernization, meant that anti-natalist policies became uncontroversial. Islam, too, had long permitted birth control. A series of Islamic conferences in the 1960s condoned the use of birth control, facilitating the adoption of population control policies in several Muslim-majority countries.

In 1983, when elective abortions within ten weeks of pregnancy were legalized, Turkey joined a number of countries that formally embraced population control as a strategy of industrial development. The law also permitted, for the first time, voluntary sterilization for men and women. Enacted in the last months of military rule, it defined “population planning”—a curious coinage that fuses “population control” and “family planning”—as “individuals having as many children as they want and when they want.”

Notably, there were no women at the National Security Council meeting where elective abortions and voluntary sterilizations were debated and legalized. For married women, the law required the husband’s consent. Though feminists today protest Erdoğan’s suggestion of a ban on abortion, saying that rights that were “won” will not be subject to negotiation, reproductive choice was not in fact “won.” Nor was it conceived of as a “woman’s right.”

Internationalizing Family Values

Erdoğan himself positions himself with conservative forces elsewhere when he says: “In many Western societies there are laws about abortion. And now we are studying these. This has its place within our own values. Abortion cannot be allowed. God forbid, a threat to [the mother’s] life and such, those are separate issues.”

Erdoğan himself positions himself with conservative forces elsewhere when he says: “In many Western societies there are laws about abortion. And now we are studying these. This has its place within our own values. Abortion cannot be allowed. God forbid, a threat to [the mother’s] life and such, those are separate issues.”

Framing women’s reproductive health and choices as a matter of population and morality, Erdoğan criticizes “the West” for its effort to limit population in Muslim-majority countries, and praises it for upholding a religiously based morality that criminalizes abortion. Dovetailing with a “right to life” discourse during the past two decades, the current Turkish prime minister’s anti-abortion stance ignores the gendered nature of bearing and rearing children.

As Doris Buss and Didi Herman show in their book Globalizing Family Values, a conservative network championing what it sees as “traditional family” values—against individualism, extramarital sexual relations, homosexuality, and abortion—has been organizing at international conferences on population and women’s rights to limit women’s right to choose.

In advance of the 1994 U.N. Population Conference in Cairo, the Vatican reportedly reached out to Iran and Libya in search of a joint Catholic-Muslim stance against population control and abortion. As Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Rafsanjani publicly stated, “The future war is between the religious and the materialists. Collaboration between religious governments to outlaw abortion is a fine beginning for the conception of collaboration in other fields.”

While theocratic states have at times made appeals on the basis of a universal morality in order to limit abortion, religious traditions have differing views on contraception and abortion. Islam permits contraception; to medieval churchmen, this was one of its sexual “horrors.” Similarly, classical Islamic doctrine, while not condoning abortion, is less rigid on the issue.

In contrast to the Vatican’s flat condemnation of abortion under any circumstances, for Muslims, saving the mother’s life has always been a valid reason for abortion. Several Muslim-majority countries also permit abortions in the early stages of the pregnancy in cases of rape and fetal development problems. In Turkey and Tunisia, women may have abortions in the first trimester without having to provide a reason. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the Vatican are committed to limiting women’s access to reproductive rights. It is unlikely that Turkey, a pioneer in expanding women’s political, economic and civil rights in the region, will ban abortion by reference to Islamic law. It is possible, however, that conservatives there will claim that religious-cultural values are expressions of universal moral laws in order to restrict reproductive choice.

Denying Choice

Today, religious conservatives suggest that universal morality trumps the rights and well-being of individual women. When asked whether women who have been raped must carry a resulting pregnancy to term, Sefer Üstün, a prominent member of Erdoğan’s party responded, “of course.” Discussing women raped in Bosnia in the 1990s, he said: “If those babies had been killed in the mother’s womb, it would have made for a bigger drama, and crime, than those perpetrated by the rapists.” This statement, coming from the chairman of the Human Rights Commission, does not bode well for women’s rights in Turkey. It threatens to restrict reproductive choice on religious grounds.

But what exactly Islam says about abortion is debated. Mehmet Görmez of the Presidency of Religious Affairs (PRA), a peculiar institution in “secular” Turkey, weighed in: “Abortion is forbidden (haram) and is murder.” His effort to fuse religion and politics glossed over disagreements between the main Islamic schools of thought over exactly when the fetus gains a soul (“ensoulment”)—ranging from 40 to 120 days from conception.

Interestingly, recent arguments for stricter interpretations of the Koran have drawn upon science as well as religious doctrine. According to Görmez, “as long as men of science, genetics experts, tell us, based on certain scientific data, that the fertilized egg cell has a heart separate from that of the mother’s, that both have separate blood circulation systems, and [the fertilized egg] is connected to the mother only through nutrition, not only [the PRA] but all religions, legal systems, see that abortion is an assault on human life.”

Turkey’s new reproductive governmentality seeks to discipline women via political institutions and religious traditions dominated by men. In exceptional cases, the director of the PRA has declared, abortion may be permitted by religious scholars, psychiatrists, and forensic doctors. The women whose bodies are subject to expert decision-making have been conspicuous by their absence.

It is unlikely that many people in Turkey will heed Erdoğan’s advice to have more children. At the time of this writing, Turkey’s government has passed legislation stipulating that Caesarians should be used only in cases of “medical necessity;” in the face of intense protest, it has not legislated further restrictions on abortion.

As feminists protest efforts to ban abortion in Turkey, they do so in a nation where reproductive choice has never really been seen as a woman’s right. This most recent reproductive governmentality, which is likely to lead to tens of thousands of unwanted pregnancies, does not bode well for women. By limiting reproductive choice, it compromises women’s health and rights.

Recommended Resources

Boli, John and M. George Thomas (eds.). Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations since 1875 (Stanford University Press, 1999). Presents a variety of case studies of the impact of international non-governmental organizations. Includes a chapter by D. Barrett and D.J. Frank that discusses how population control discourse was brought to the Third World in the 1960s.

Buss, Doris and Didi Herman. Globalizing Family Values: The Christian Right in International Politics (University of Minnesota Press, 2003). Documents Christian Right activism at the United Nations, and includes a chapter on its gender agenda and the institutional leadership role of the Vatican.

Hessini, Leila. “Abortion and Islam: Policies and Practice in the Middle East and North Africa,” Reproductive Health Matters (2007), 15:75-84. Provides an overview of abortion policy and practice in 21 Muslim-majority countries.

Kürtaj Yasaklanamaz. “Ethical Evaluation of the Legal Dimension of Abortion in Turkey and the World” (2006) by Muhtar Çokar. Provides historical background on abortion policies in Turkey (in Turkish). Kürtaj Yasaklanamaz is a website created in summer of 2012 by feminist activists in response to Erdoğan’s comments. Some of its content is available in English at saynoabortionban.com.

Maguire, C. Daniel (ed.). Sacred Choices: The Case for Contraception and Abortion in Ten World Religions (Oxford University Press, 2001). Discusses traditions of reproductive choice within major religions. Includes a chapter by Sa’diyya Shaikh on contraception and abortion in Islam.

The Population Studies Institute at Hacettepe University. The 2008 report of the Turkish Demographic and Health Study (TDHS), part of the worldwide DHS Project, is available on the Institute’s website. The Institute’s mission is to train qualified demographers and contribute to population policymaking and implementation.

Further Reading

For more information on the data from Turkish Demographic and Health Surveys, check out Hacettepe University’s Institute of Population Studies.