The Sadness of the Border Wall

It took two days on the bus for Catalina Cespedes and her husband Teodolo Torres to get from their hometown in Puebla—Santa Monica Cohetzala—to Tijuana. On a bright Sunday in May, they went to the beach at Playas de Tijuana. There, the wall separating Mexico from the United States plunges down a steep hillside and levels off at the Parque de Amistad, or Friendship Park, before crossing the sand and heading out into the Pacific surf.

Sunday is the day when families meet through the border wall. The couple had come to see their daughter, Florita Galvez.

Florita had arrived that day in San Ysidro, the border town a half hour south of San Diego. Then she went out to the Border Field State Park, by the ocean two miles west of town. From the parking lot at the park entrance it was a 20-minute walk down a dirt road to the section of the wall next to the Parque de Amistad.

Copyright David Bacon

At 11am, Catalina and Florita finally met, separated by the metal border. They looked at each other through the metal screen that covers the wall’s bars, in the small area where people on the U.S. side can actually get next to it. And they touched. Catalina pushed a finger through one of the screen’s half-inch square holes. On the other side, Florita touched it with her own finger.

Another family shared the space with Catalina and Teodolo. Adriana Arzola had brought her baby Nazeli Santana, now several months old, to meet her family living on the U.S. side for the first time. Adriana had family with her also—her grandmother and grandfather, two older children and a brother and sister.

It was very frustrating, though, to try to see people on the other side through the half-inch holes. So they moved along the wall to a place where the screen ended. There the vertical eighteen-foot iron bars—what the wall is made of in most places—are separated by spaces about four inches wide. Family members in the U.S. could see the baby as Adriana held her up.

Copyright David Bacon

But only from a distance. The rules imposed by the U.S. Border Patrol in Border Field State Park say that where there’s no screen, the family members on that side have to stay several feet away from the wall. So no touching.

I could see the sweep of emotions playing across their faces and in their body language. One minute, the grandmother was laughing. The next, there were tears in her eyes. The grandfather just smiled and smiled. Adriana talked to her relatives and tried to wake the baby up. Her brother leaned on the bars with his arms folded against his eyes, and her sister turned away, overcome by sadness. On the U.S. side, a man in a wheelchair and two women with him looked happy just to have a chance to see their family again.

Some volunteers, most from the U.S. side, called Friends of Friendship Park have tried to make the Mexican side more pleasant and accommodating for families. The older children with Adriana sat at concrete picnic tables. While family members talked through the wall, they used colored markers, provided by the Friends, to make faces and write messages on smooth rocks. Around them were the beginnings of a vegetable garden where, later in the afternoon, one of the volunteers harvested some greens for a salad.

Copyright David Bacon

Members of the Friends group include Pedro Rios from the U.S./Mexico Border Program of the American Friends Service Committee, and Jill Holslin, a photographer and border activist. On the U.S. side, another of the participating groups—Angeles de la Frontera, or Border Angels—helped the families that came to the park. “We’re here seven or eight times a month,” said Enrique Morones, the group’s director. “People get in touch with us because we’re visible, or they know someone else we helped before.” Border Angels helps set up the logistics so that families can arrive on both sides at the same time, often coming from far away.

Weekend visiting hours, from 10am-2pm, are the only time the Border Patrol allows families to get close to the wall for reunions. Once a year, they open a doorway in the wall. Watched closely by BP agents, family members are allowed to approach the open door one by one, and then to hug a mother or father, a son or daughter, or another family member from the other side. To do that, people have to fill in a form and show the agents they have legal status in the U.S. During the rest of the year, the Border Patrol doesn’t ask about legal status, although they could at any moment. For that reason, Border Angels tells families not to go on their own.

Such carefully controlled and brief encounters are the ultimate conclusion of a process that, at its beginning, had no controls at all. Before 1848, there was no border here whatsoever. That year, at the conclusion of what the U.S. calls “the Mexican War,” the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Mexico was forced to give up 529,000 square miles of its territory. The U.S. paid, in theory, $15,000,000 for the land, but then simply deducted it from the debt it claimed Mexico owed it. U.S. troops occupied Mexico City to force the government there to sign the treaty.

Copyright David Bacon

The so-called “Mexican Cession” accounts for 14.9% of the total land area of the United States, including the entire states of California, Nevada, and Utah, almost all of Arizona, half of New Mexico, a quarter of Colorado, and a piece of Wyoming. Some Congress members even called for the annexation of all of Mexico.

At the time, the city of San Diego was a tiny, unincorporated settlement of a few hundred people. It was considered a suburb of Los Angeles, then still a small town. San Ysidro didn’t exist, nor did Tijuana. To mark the new border, in 1849 a U.S./Mexico boundary commission put a marble monument in the shape of a skinny pyramid marking where they thought the line should go. A replica of that original pyramid today sits next to the wall in the Parque de Amistad. On the U.S. side, the road leading from San Ysidro to Boundary Field State Park is named Monument Road, and the area is called Monument Mesa.

Early tourists chipped so many pieces from the marble pyramid that it had to be replaced in 1894. The first fence was erected, not along the borderline, but around the new monument to keep people from defacing it. The line itself was still unmarked, fifty years after it had been created.

Copyright David Bacon

The Border Patrol was organized in 1924. Before that, there was no conception that passage back and forth between Mexico and the U.S. on Monument Mesa had to be restricted. The Federal government only assumed control over immigration in 1890, when construction began on the first immigration station at Ellis Island in New York harbor. Racial exclusions existed in U.S. law from the late 1800s, but the requirement that people have a visa to cross the border was only established by the Immigration Act of 1924. The law also established a racist national quota system for handing out visas.

In the 1930s the Border Patrol terrorized barrios across the U.S., putting thousands of Mexicans into railroad cars and dumping them across the border. Even U.S. citizens of Mexican descent and people who just “looked Mexican” were swept up and deported. Trains carried deportees to the border stations in San Ysidro and Calexico, but on Monument Mesa there was still no formal line to keep people from returning.

That changed after World War II, when barbed wire was stretched from San Ysidro to the ocean. Mexicans called it the “alambre,” or the wire. Those who crossed it became “alambristas.” Yet enforcement was still not very strict. During the 1950s and early 1960s, thousands of Mexican workers were imported to the U.S. as braceros, while many other migrants also came without papers. In the Imperial Valley, on weekends during the harvest, those workers would walk into Mexicali, on the Mexican side, to hear a hot band or go dancing, then hitch a ride back to sleep in their labor camps in Brawley or Holtville.

Copyright David Bacon

In 1971, Pat Nixon, wife of Republican President Richard Nixon, inaugurated Border Field State Park. The day she visited, she asked the Border Patrol to cut the barbed wire so she could greet the Mexicans who’d come to see her. She told them, “I hope there won’t be a fence here too much longer.”

Instead, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act in 1986. Although many remember the law for its amnesty for undocumented immigrants, IRCA also began the process of dumping huge resources into border enforcement. A real fence was built in the early 1990s, made of metal sheets taken from decommissioned aircraft carrier landing platforms. The sheets had holes, so someone could peek through. But for the first time, people coming from each side could no longer physically mix together or hug each other.

That old wall still exists on the Mexican side in Tijuana and elsewhere on the border. But Operation Gatekeeper, the Clinton Administration’s border enforcement program, sought to push border crossers out of urban areas like San Ysidro, into remote desert regions where crossing was much more difficult and dangerous. To do that, the government had contractors build a series of walls that were harder to cross.

Copyright David Bacon

On Monument Mesa, the aircraft landing strips were replaced in 2007 by the 18-foot wall of vertical metal columns. Two years later, a second wall was built behind the first on the U.S. side. The area between these two walls became a security zone in which the Border Patrol restricts access to the wall itself to just four hours on Saturday and Sunday. The metal columns were extended into the Pacific surf.

In Playas, though, the wall is just a sight to see for the hundreds of people who come out to the beach on the weekend. The seafood restaurants are jammed, and sunbathers set up their umbrellas on the sand. Occasionally, a curious visitor will walk up to look through the bars into the U.S. or have a boyfriend or girlfriend take a picture next to the wall, uploading it to Facebook or Instagram for their friends.

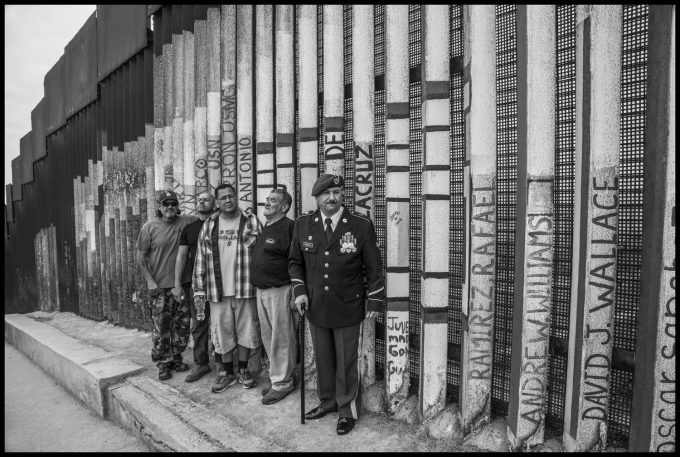

The wall itself at the Parque de Amistad has become a changing artwork. As the bars rust, they’ve been painted with graffiti that protests the brutal division.

One section bears the names of U.S. military veterans who’ve been deported to Mexico, with the dates of their service and death. A deported veterans group comes down on occasional Sundays, some in uniform. In angry voices, they ask why fighting the U.S.’s wars didn’t keep them from being pushed onto the Mexican side of the wall.

Copyright David Bacon