The Struggle to Save Abortion Care

“Some will rob you with a six gun, some with a fountain pen.” This line from an old Woody Guthrie song is an apt description of the vulnerability of abortion providers in the United States. Clinics have long been subject to physical attacks: eleven individuals have been murdered by anti-abortion extremists, thousands more have been terrorized at their homes and offices, and numerous clinics have been vandalized, even destroyed by fire-bombings. More recently, a harsh new regulatory regime—Guthrie’s “pen”—comprising onerous restrictions passed by state legislatures and hostile inspections by health departments threaten the ability of providers to keep their facilities open and to sustain their vision of “woman-centered” care. As a longtime abortion clinic administrator told me, “Regulatory interference is the new frontier of the anti-abortion movement.”

Anti-abortion politicians have sought to regulate abortion ever since the Roe v Wade decision in 1973. More than 1,200 restrictions have been passed by state legislatures over the past 45 years. But after the 2010 midterm elections, which brought many state legislatures and governorships into total Republican control (a change reinscribed by the 2014 midterms), these restrictions have metastasized, and many are far more serious than earlier iterations. More than 400 restrictions have passed at the state-level since 2011. In January 2018, the Guttmacher Institute concluded that some 58% of American women live in states “either hostile or extremely hostile to abortion rights.”

Earlier restrictions on abortion focused on the “demand” side, mandating parental notifications and consent for minors and imposing waiting periods, for example. Today’s restrictions focus on the “supply side,” targeting abortion facilities. Two of the most consequential of these regulations are, on their face, aimed at patient health. These require that clinics are certified as Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASCs) and that abortion doctors have admitting privileges at a hospital within a certain distance of their practice. The ASC requirement stipulates that abortion clinics essentially transform themselves into small hospitals, with specifications around air flows, corridor widths, space for janitorial lockers, and specialized sinks—upgrades that can cost well over a million dollars—as well as compliance with the stringent sterility guidelines of hospital operating suites.

The hospital admitting privilege requirement is virtually impossible for many clinics to meet, but for two quite different reasons. The first is that, due to abortion politics, many local hospitals refuse to grant abortion providers admitting privileges. They don’t want to draw community protest. A notable case occurred when Dr. Willie J. Parker, a board-certified obstetrician/gynecologist and former medical school faculty member who trained at the University of Michigan and Harvard, among other institutions, sought to provide abortions in Mississippi’s sole clinic, but was refused privileges at every hospital to which he applied. (Successful court challenges ultimately permitted Dr. Parker to perform abortions in the state).

Yet another, quite ironic, obstacle for providers seeking admitting privileges is that many hospitals require any physician with privileges to have at least ten patient admissions per year. But abortion provision is so safe that it is extremely rare for any abortion doctor to have such an extensive record of hospital admissions. Tammi Kromenaker, the director of North Dakota’s only clinic, once commented to a reporter, “I would never employ a doctor who had to admit ten patients a year. That would mean they were a terrible doctor.” Kromenaker explained that her clinic had only one hospital admission in ten years. (Fewer than 0.3% of American abortion patients experience a complication that requires hospitalization, and these women typically present at an emergency room near their homes, often some distance from the facility in which their abortion took place). Indeed, the National Academy of Medicine recently reaffirmed the safety of clinic abortions and criticized numerous state restrictions for their negative impact on the quality and safety of abortion care.

The ASC and admitting privileges restrictions and others imposed on abortion clinics are called TRAP laws by pro-choice lawyers (Targeted Restrictions of Abortion Providers), and legal scholars say they reveal the extent of “abortion exceptionalism” in our political system. Observers note that in many of the states requiring ASC standards for abortion clinics, outpatient facilities offering procedures with comparable levels of complexity and risk—from vasectomies to sigmoidoscopies and minor neck and throat surgeries—are free of such requirements. Colonoscopies have a mortality rate 10 times higher than abortion but, in Texas, which has some of the most stringent abortion restrictions, colorectal health providers are not subject to ASC requirements. More than 160 clinics providing abortions have closed since 2011, in large part because they cannot meet regulatory demands.

In this hostile environment, abortion rights supporters had a rare moment to celebrate in June 2016, when the Supreme Court, in the Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt case (WWH) overturned Texas’s ASC and hospital admitting privileges laws. The most immediate result was the continued operation of a number of Texas clinics that had been closed or were operating under temporary injunction. Had the decision gone the other way, the number of abortion clinics in Texas would have gone down to 10 from a previous high of about 40. (Currently, there are about 20 clinics in operation in Texas; a number of those that had closed were unable to reopen, as staff had dispersed and building leases had expired).

Abortion rights supporters were additionally cheered because the Court’s decision signaled, for the first time, that restrictions on abortion must be based on scientific evidence rather than the political whims of state legislators. Many social scientists were particularly encouraged that the Majority opinion made ample use of the work of sociologists and public health researchers. Not surprisingly, researchers had extensively documented that the most severe consequences of abortion clinic restrictions would fall on the poorest women in Texas, who are disproportionately women of color.

The elation was short-lived. Immediately after the decision, the state of Texas introduced yet more restrictions on abortion, including a requirement that fetal remains resulting from abortions be given funerals, a measure that would add considerable cost to the procedure and would upset many abortion patients. (This measure is currently in litigation). And though some states dropped admitting privileges and ASC requirements after the WWH decision, others did not, and “red” state legislatures continue to pass new restrictions.

The biggest threat to abortion care nationally came just five months after the WWH decision, with the election of Donald Trump and his ardently anti-abortion running mate, Mike Pence. The new administration quickly nominated Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. He is expected to be an additional vote to overturn Roe as soon as a relevant case reaches the Court. In June 2018, after this research was completed, Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement, throwing abortion rights supporters into panic mode because of Trump’s declared intention to nominate “pro-life” justices. Just prior to Kennedy’s announcement, Gorsuch made clear his antiabortion sympathies, voting with the majority in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra, a decision that both released crisis pregnancy centers from the obligation to state their true antiabortion aims, and reaffirmed that abortion providers can be compelled to deliver state-mandated scripts to their patients. (As this article went to press, Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh, a judge with a longstanding record of hostility to abortion, has made the fate of Roe the leading issue in the confirmation battle).

How Restrictions Impact Clinic Care

Many clinics have closed under this new regulatory regime; others remain open, striving to meet states’ requirements and provide care. My conversations with some 50 abortion providers (including clinic directors and managers) over the past several years, both before and after the landmark WWH decision, reveal how challenging it has been to keep their clinics open and sustain the “woman-centered” abortion care that has been carefully developed over the past 45 years.

In a focus group of abortion facility directors, a woman who had been involved in abortion care since Roe said: “In the first 10 years post-Roe, our whole mission as independent providers was about pulling this caring service out of a hospital situation. We fought really hard not to be in a hospital… to offer personalized care in a woman-to-woman manner that the safety of the procedure certainly made possible… [W]e would care for women in a way that make it as personal and as good an experience as you could possibly have… like somebody went out of their way to help you feel comfortable today.”

The speaker recounted how she and a colleague had approached herbal tea makers to find a blend helpful for soothing a woman’s uterus after the procedure—a gesture that would be impossible to implement today in states that still have ASC regulations, because offering tea or snacks to patients would violate sterility requirements. Another longtime provider in the South lamented, “Health care is about nurturing. And if [ASC rules] take away our ability to nurture our patients, then we have really lost.”

Tearfully, yet another provider described how mandated ASC changes (in effect in her state, despite the WWH decision), changed the clinic: “You walk into our surgery center, and it’s so cold, and intimidating… there’s no art. The lights are too bright, the recovery rooms smell like bleach. Everyone’s wearing gowns. We have actually implemented doulas, but they’re still gowned up in the same things. The warmth is gone.”

The entanglement of abortion politics with health departments also impinges on abortion care. Numerous clinic staff reported intensified, stressful inspections by state and local health departments and other agencies after 2010. To be sure, some portion of clinic inspections was regularly scheduled, as part of a state’s mandate to inspect all licensed health care facilities, but as the abortion issue heated up in many states after the 2010 elections, clinic staff reported both an intensification of the number of inspections—often unannounced—as well as a palpably increased tension with inspectors. (One clinic reported 11 unannounced visits in 8 months, including two separate visits on one memorable day.)

Some inspections aimed to ensure clinic compliance with ASC regulations or other new guidelines. Others were responses to larger political events in abortion politics. For example, after the summer 2015 release of misleading “sting” videos about alleged sales of fetal tissue in Planned Parenthood clinics, one clinic director (not affiliated with Planned Parenthood) found agents sent by the state’s Attorney General knocking on her clinic’s door. “They said they were there to see if we were ‘selling baby parts.’” Some of the unannounced inspections were triggered by anonymous complaints; many were later revealed to have been made by anti-abortion groups. One director told me about an inspection prompted by a Facebook complaint left by abortion opponents.

A Midwestern clinic staffer reported an agonizing occasion that followed quickly on her state’s governor declaring his presidential candidacy. The clinic had been regularly inspected for years, mainly without incident. “This year it was different. They were here for two days… they kept asking me to leave the room, and they’d get on the phone with somebody in [state capitol]. Then, they’d come back and ask to see such and such… I mean, it went on and on… someone else was pulling the strings.” A clinic director in the South recalled an inspection that occurred as the clinic was involved in a high-profile state-law challenge. It involved haz-mat clad nurses from the state health department sifting through the clinic’s garbage dumpster because abortion opponents had claimed, untruthfully, that aborted fetuses were being discarded there. As patients watched, the director said, “Our clinic was turned into a crime scene,” complete with yellow tape around the dumpster.

Even where hostility is not blatant, repeated inspections disrupt clinic proceedings, demoralize staff, and upset patients, especially the unannounced inspections. Staff in one Midwestern clinic, which had recently seen an intensification of inspections, spoke about “men with guns” abruptly entering the clinic and “freaking out” both staff and patients. These were (routinely armed) Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents who came, the staff believed, in response to an anti-abortion group’s “tip” regarding improper dispensation of drugs.

Poignantly, several senior clinic staff compared the current state of siege they felt under the current regulatory climate to the large-scale blockades abortion clinics experienced in the 1980s and early 1990s (until the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances legislation signed by President Bill Clinton made such actions a federal crime). These veterans ruminated on the levels of public support clinics received then: “The blockades were really public, and they were physical, but people on the outside saw it, and they sympathized with us. The police came, and they were on our side. But now, with the onslaught of attacks through the regulatory system and the legislative system, it’s invisible to the majority of Americans. People have no idea what’s happening. It’s not thugs invading our clinic, its state-sanctioned harassment.”

Older Regulations Get Worse

The new regulatory environment of ever-stricter restrictions and heightened surveillance of abortion providers co-exists, of course, with the older restrictions still in force. Many of these, including such as waiting periods (mandatory time between when a woman is first counseled about abortion and when she can receive one) and state-mandated scripts for counseling patients, have been updated to impose even harder obstacles. For example, 24-hour waiting periods have been increased, in some states, to 48 or 72 hours. These delays are obviously problematic. In some cases, longer waiting periods can push a woman beyond the gestational limit for abortion in that state. Researchers estimate that some 4,000 women a year are turned away from abortion clinics because they arrive too late in their pregnancies.

But even the 24-hour waiting periods can create havoc, especially in the 14 states where women have to appear in person for the first visit. Two separate clinic visits can mean two days of lost wages and two days of paying for childcare (some 60% of abortion patients have children, and nearly half of all abortion patients live below the federal poverty level and another 25% have incomes from 100-200% of that level). Further, since already-scarce abortion clinics tend to be located in metropolitan areas, rural women may face six hours or more of driving to get to their clinic. Thus waiting periods mean finding places to stay in the city and, because many abortion patients are low-income, patients and sometimes their family members are forced to spend one or more nights sleeping in their cars in the clinic parking lot.

State-mandated counseling scripts also compromise abortion providers’ vision of abortion care. These scripts, passed by red state legislatures, essentially compel clinic staff to lie. They include misleading and discredited statements claiming links between abortion, breast cancer, suicide, and infertility, negative psychological effects of abortion, and the idea that certain types of abortion procedures can be “reversed.” In several states, providers must inform patients that abortion will “terminate the life of a whole, separate, and unique human being.” The Guttmacher Institute recently concluded that 29 states “impose specific abortion counseling requirements that go beyond what is necessary for informed consent.”

These kinds of counseling mandates are troubling in several ways: first, they force staff to violate professional ethics by telling their patients falsehoods. Additionally, spending time delivering false and often upsetting messages to patients detracts from what counseling staff want to accomplish: discussing patients’ feelings about the upcoming procedure, answering questions, and ascertaining that the patient is not being coerced into an abortion.

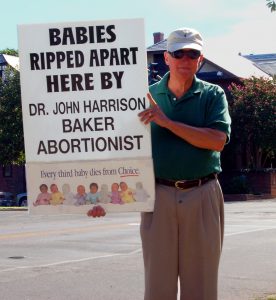

Patients’ exposure to protestors is another factor complicating abortion care. Nearly all abortion facilities regularly draw protestors, but the number of protestors and the character of the protests vary widely. In some instances, protestors are a handful of largely silent individuals; in others, crowds of hundreds and, on special coordinated occasions such as national days of protest, thousands surround a clinic with enormous grotesque posters purporting to show aborted fetuses. Disregarding local noise ordinances, protest leaders screech through bullhorns at patients and their companions, calling on them not to “murder your babies.” African-American patients are routinely besieged with targeted shouts from White protestors: “You could be killing the next Martin Luther King.”

Clinics now commonly warn patients about protestors and station volunteers outside to greet patients and try to shield them from aggressive protestors, yet clinic staff report that some patients remain very upset after such confrontations. In some situations, the noise filters into clinic counseling rooms, and staff are reduced to playing loud music to drown out the protestors. Similar to the mandated counseling scripts, calming down patients shaken by protestors takes time away from the counseling staff feels is actually necessary.

Chaos and Resistance in the Abortion Clinic

The chaotic environment in which much of abortion provision takes place today involves a new round of challenges to the personal safety of providers and patients. Since Trump’s election, the National Abortion Federation reports increases in aggressive incidents—stalking, vandalism, bomb threats—at clinics. Starting in the fall of 2017, clinics have even experienced “invasions” involving extremists bursting into clinic waiting rooms and accosting patients—activity not seen in the U.S. since the early 1990s.

Further, since Trump’s election, not only are some clinics are facing hostility from state legislatures, virtually all of them are dealing with hostility from the federal level. Beyond the Supreme Court, the Trump-Pence administration has nominated numerous, conservative lower court judges with anti-abortion records who are expected to uphold increasingly arduous restrictions on abortion care. It has given federal jobs to individuals whose main credential appears to be a history of anti-abortion activism. One glaring example is Scott Lloyd, named head of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, who has gained prominence by trying to prevent undocumented, detained teenagers from having abortions, even personally visiting these young women in an attempt to dissuade them from abortion. (Ultimately the ACLU succeeded in overruling Lloyd’s denial of the abortions.)

Given all these obstacles, I asked providers how they keep going. Not surprisingly, the providers cited their profound belief in the importance of reproductive justice and a very direct sense of commitment to their patients. The director of a Midwest clinic that sees frequent and very aggressive protesting, told me: “It’s because of the patients… Because when you go into a room and you can hold the patient’s hand and she says, ‘Thank you for being here,’ it makes it worth it. You temporarily forget about the five people who just threatened to beat you up…. [I stay] because I love this work.”

Abortion care providers are also fueled by a determination to not let the “antis” win. A staff person from a city in which national anti-abortion groups had made significant (and ultimately unsuccessful) attempts to shut down the sole remaining clinic acknowledged that what keeps her going, beyond a commitment to her patients, is the satisfaction of standing up to her foes. She told me that the fact that a nationally known leader of an antiabortion group is “pissed off” by her efforts to continue offering abortion care, “feels good to me… gets fire in my belly.”

I also asked providers about their efforts to sustain the vision of “good” abortion care, even under chronic siege. Those providers whose clinics had been turned into ASCs acknowledged the challenges of bringing “warmth” into a hospital-like setting. Those who had felt compelled to implement, for security reasons, locked doors and restricted entrance conceded that the measures did not send a “welcoming” message, but inside, they made considerable efforts to make the setting as warm as possible. One director, mindful of the negative image of abortion facilities as “mills,” told of her fanatic devotion to cleanliness: “I want this clinic to look like a place I’d bring my daughter to. I want patients to think they could bring their daughters here.”

Most fundamentally, providers remain firm in their commitment to one of the basic tenets of woman-centered care: that there is no “one size fits all” model of abortion. In practice, this means each woman must be “met where she is at,” in the common phrasing of providers. The majority of patients who appear resolved to have an abortion are given information about the procedure, have any questions answered, are offered routine counseling, and, as is standard in abortion facilities, are queried as to whether coercion is involved in their decision. The small minority of patients who present as deeply conflicted about their decision—for example, saying, “God will never forgive me”—are offered more extended counseling, and, in rare instances, have their abortions postponed to allow them more time for reflection.

The contemporary abortion clinic is both a site of chaos, under siege by legislators and protestors, and resistance, affirmed by mission-driven clinic staff and the continued need for abortion services. Among those I interviewed, some were puzzled when I asked why they continued to provide abortions when threats are coming from more and more places. One manager said simply and powerfully, “Carole, there’s joy in this work.”

Recommended Readings

Americans United for Life. 2016. Model Legislation and Policy Guidelines. The “playbook” for antiabortion legislators, from a national legal group, this document has inspired numerous state-level restrictions.

Esme Deprez. 2016. “Abortion Clinics are Closing at a Record Pace,” Bloomberg News. Explains the impact of abortion restrictions on clinic closures and reveals the geographical distribution of such closures.

Carole Joffe. 2010. Dispatches from the Abortion Wars: The Costs of Fanaticism to Doctors, Patients and the Rest of Us. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Discusses the “woman-centered” model of abortion care providers are struggling to sustain.

Willie Parker. 2017. Life’s Work: A Moral Argument for Choice. New York: Simon and Schuster. A memoir by a physician whose strong Christian beliefs led him to care for women in his native South.

Dawn Porter. Trapped. 2016. trappeddocumentary.com. The film demonstrates how abortion restrictions affect providers and patients.

Comments 1

Ashwin

October 30, 2018Synchronization is so important for every windows 10 operating system and this Online tutorial teaches sync files windows 10 how to do this process easily.