The Unborn and the Undead

It was most certainly a lark, a political thought experiment, but a poignant one. A shooter at the Colorado Springs office of Planned Parenthood—the largest single provider of reproductive health services, including abortion, in the United States—had just killed a police officer and two civilians and injured nine others. Representative Stacey Newman’s (D-Missouri) responding gambit was to juxtapose the country’s lax gun laws with its strict restrictions on abortion. Her proposed bill, which will not be heard nor passed, would subject gun purchasers to the same regulations placed on those seeking an abortion in her state.

Among other things, it would mandate that gun buyers wait 72 hours before purchase, the same waiting period those who require an abortion must wait in Missouri—a state with only one active abortion clinic. Buyers would need written permission from a doctor testifying to their basic sanity. They would watch a cautionary video about fatal firearm injuries and make a mandatory visit to an emergency trauma center where they would see the visceral impact of gun violence. Lastly, buyers would meet with those who have lost family members and with civic leaders who have performed funerals for victims. The Colorado Springs shooter, it’s important to add, had called himself a “warrior for babies.”

The fledgling bill crystallizes a contradiction at the heart of the conservative movement: heavy-handed, interventionist government for some (namely, women) and laissez-faire autonomy for others (specifically, gun owners). This contradiction pivots on a full-throated defense of White, masculine privilege. Thus the outlandish statements made by Republican politicians in recent years that mix startling ignorance with willful disparagement of women’s bodies and minds.

A sample: Rep. Todd Akin (R-Missouri) declared that in cases of “legitimate rape,” a woman’s body would block an unwanted pregnancy, meaning there is no need for an allowance for rape and incest victims to access abortions. (The scarcely imaginable implication is that in cases of rape or incest where the victim is impregnated, she is a willing accomplice). Presidential candidate Ben Carson cited “the many stories of people who have led very useful lives who were the result of rape or incest” and said he “would not be in favor of killing a baby because the baby came about in that way.” Former Governor of Florida, Jeb Bush, said of Planned Parenthood’s federal funding: “I’m not sure we need half a billion dollars for women’s health issues.”This flamboyant rhetoric is accompanied by a serious political strategy to end abortion. In 2015, states passed no less than 57 restrictions on women’s right to choose. Central to these efforts is the assumption that women should not be trusted to control their own bodies and that the rights of the unborn trump those of adult women. In this respect, the Tea Party wave pouring into statehouses since 2011 is less conservative than patriarchal. And patriarchy is a kind of political undead: no matter how many gains feminists and allies make, it reemerges like a zombie to feast on the women and families that are its lifeblood.

In this issue’s Viewpoints, Katrina Kimport surveys the dizzying number of abortion restrictions passed in recent years. Some severely curtail access to abortion while others are openly misogynistic. What they share is a view of women as dubious ditherers incapable of making informed and responsible decisions.

For her part, Susan Markens provides an historical perspective on the permutations of anti-abortion discourse, which today focuses less around the moral status of the fetus and more on the moral duty of women to procreate. Abortion, opponents argue, alienates women from their essential nature as mothers and nurturers.

Drew Halfmann examines public attitudes toward abortion over time, finding that opinion has remained stable, generally in favor of abortion provision with some restrictions. But what has changed is the vigor of the Republican Party, its donors, and grassroots supporters. Together, they push for changes that radically outpace any corresponding shift in public opinion.

Kimala Price considers the strangely racialized language of the anti-abortion movement. In some cases, abortion opponents claim that the clamor for reproductive rights is part of a conspiracy to reduce the number of Black babies. The lack of accessible, affordable healthcare is patronizingly repackaged into care for would-be victims of a “Black genocide.”

Finally, Deana Rohlinger explores the politically concocted controversy surrounding Planned Parenthood and the ongoing efforts to remove its public funding. As the pro-life right has gotten more and more successful at the state and local levels, it’s becoming harder for candidates to prove their conservative bona fides unless they speak loudly, tread heavily, and act sensationally. Democrats and the media have provided lukewarm resistance and shallow coverage, putting up a pitiful fight for the rights of American women.

– Shehzad Nadeem

- The Continuing Significance of Gender, by Susan Markens

- Complicating the Story on Abortion Restrictions, by Katrina Kimport

- A Right Turn and a New Era, by Drew Halfmann

- The Emergence of The Black Fetus, by Kimala Price

- Politics and Planned Parenthood, by Deana A. Rohlinger

The Continuing Significance of Gender

by Susan Markens

In the U.S., political discourse about reproductive rights seems to revolve around divergent and intractable positions on the moral status of the fetus. Abortion politics is a form of symbolic politics—a battle over meanings—and as a result legislative battles over regulations reflect debates well beyond legality and the status of the fetus. Since its regulation by the state in the 19th century, one issue that has permeated fights over abortion restrictions in the U.S. is the inextricable linking of abortion rhetoric to gendered ideologies that reflect assumptions, anxieties, and conflicts about the status of women in society.

Historical scholarship has documented that moral concerns about the fetus were articulated in the mid-19th century, but they were not the dominant theme. The dominant theme was anxiety about declining female fertility—in particular, the decrease in births to White Anglo-Saxon women. This was promulgated by American physicians who successfully campaigned to restrict abortion access. By lamenting the abdication of motherhood that abortion represented and promoting an essentialist discourse about (some) women’s moral duty to society, medical professionals and social advocates clearly drew on both gendered and racial ideologies prominent at the time. Meanwhile, although there is debate about 19th century feminists’ position on abortion, it is clear that suffragists’ such as Susan B. Anthony’s opposition to abortion centered on concerns that abortion allowed for men’s unfettered sexual access to women. Their discomfort with abortion concerned not the fetus but instead rested on traditional gendered assumptions regarding both men’s and women’s sexuality. Suffragists positioned women as victims of males’ uncontrollable sexual desires, representing, for them, yet another instance of wives’ legal servitude to men in marriage.

Contemporary discourses about abortion and reproductive rights remain enmeshed in larger ideological debates about maternity and female sexuality. For instance, sociologist Kristin Luker’s ground-breaking work on abortion activists in the decades surrounding the Roe decision demonstrated that, beneath the surface of disputes over the status of the fetus, activists were motivated by two distinct worldviews about women’s roles in society. For abortion rights activists, legalized abortion symbolized women’s ability to free themselves from an identity solely based on motherhood. Among abortion opponents, abortion’s threat to traditional families and women’s primary identity as mothers and care takers motivated activism. As a result, opponents of abortion rights viewed the liberalization of abortion laws as denigrating since, to them, abortion disrupted women’s “natural” ties to children and family. Furthermore, it devalued essential female traits of nurturance.

Other gendered discourses and ideologies can also be distilled in contemporary debates. For instance, drawing on the cultural expectation of mothers as selfless in their actions toward (future) children, abortion opponents have labeled women who have abortions as selfish. This reinforces an expectation that women should put children’s needs and desires before their own. Meanwhile, recent research has found that some anti-abortion activists have promoted a different narrative—that of women as victims. In this view, women are victims as they are pressured to abort rather than follow their essential desires to mother. Expressions of regret are then used to demonstrate how abortion undermines women’s “natural” maternal impulses.This brings us to the 2015 #ShoutYourAbortion Twitter campaign created in response to Republicans’ attempts to de-fund Planned Parenthood. By encouraging women to publically acknowledge their abortions, the initiators of this grassroots campaign specifically took on the stigma and shame produced by anti-abortion rhetoric. Tweets such as “No traumatic backstory: Didn’t want kids. Couldn’t afford kids. Contraceptive failure with casual bf [boyfriend]. Not one regret,” confronted the narratives of regret and victimhood. With an outpouring of proclamations and perspectives, this grassroots effort also countered the racial and classed discourse that “good women” don’t have abortions. It even served as a public acknowledgement of female sexuality and desire, decoupled from procreation.

Indeed, ongoing societal discomfort with female sexuality—particularly outside the context of committed heterosexual relationships—is visible in the not-surprising backlash to the #ShoutYourAbortion campaign. Twitter replies included “Maybe you shouldn’t let various men drop semen in you. I bet you regret those VDs [venereal diseases] that you have,” “Why didn’t you keep your whore legs together?” and “How is it owning your own body when you loaned it out to some dude to impregnate you?” Such comments show unmistakably that contemporary conflicts over abortion rights go beyond concerns about the fetus. These conflicts symbolize many things, most clearly revealing the continuing significance of gender to debates and discourses about abortion and reproductive rights.

Complicating the Story on Abortion Restrictions

by Katrina Kimport

For supporters of abortion rights, the 282 state-level abortion restrictions enacted in the last 5 years is a frequent talking point—and, for some, evidence of a war on women. But such brute force frequency counts miss the qualitative differences among the proposed restrictions. Not all restrictions are the same in their material effect on abortion access.

Closer examination of the regulations themselves reveals some that clearly harm women’s access to abortion, while others discursively devalue women’s decision-making, but do not interfere with access to care. Here, I focus on four common types of abortion restrictions and consider their effects.

First, I consider ambulatory surgery center (ASC) standards. Twenty-two states require abortion-providing facilities to meet the standards of an ASC, which include having hallways of a certain width, hands-free sinks, and no lights with dimmer switches. Framed as furthering women’s health and safety, such specifications are medically unnecessary for the vast majority of abortions. Facilities that do not meet these standards—usually because they never had a medical need to do so—often find the cost of remodeling prohibitive and are forced to close their doors. This has clear material effects on women’s access to care. If a currently enjoined 2014 ASC requirement in Texas goes into effect, an estimated 12 clinics will be forced to close, leaving around 10 clinics for the entire state.

Second, many states have regulated abortion care through admitting privileges requirements. Fifteen states mandate that physicians who perform abortions have admitting privileges at a local hospital. The claimed justification—that it ensures quality care for women—is dubious. Abortion is an exceedingly safe procedure, with a major complication rate of less than 1% (lower than other common, outpatient procedures like colonoscopy). This low complication rate, in addition to rending admitting privileges unnecessary, makes it difficult for physicians to meet most hospitals’ minimum referrals criteria for securing admitting privileges—they just don’t admit enough patients to justify the hospitals’ administrative burden. Further, any woman who did experience a complication could access hospital care via an emergency room, regardless of whether her physician had admitting privileges. In practice, this requirement has proven an insurmountable obstacle to ensuring access to abortion in strongly anti-abortion states. In Mississippi, no hospital will grant admitting privileges to the physicians who provide abortions at the single abortion facility in the state. But for a current injunction on the law, there would be no abortion provider in Mississippi.

Third, states have implemented waiting periods and two-visit requirements for women seeking abortion care. Thirteen states require women to make 2 trips in order to have an abortion, with a mandatory “waiting period” between the visits, ostensibly to ensure they fully consider their abortion decision. Waiting periods range from 24 hours to 72 hours. The requirement of an additional visit can mean additional missed work, the need to secure additional childcare, and increased travel expenses, especially for women who have to travel significant distances to reach a provider (some states waive the waiting period for women who live more than a certain distance from a provider). These additional hurdles may prove too much for a small number of women to obtain abortion care, but, more commonly, they are experienced as expensive hassles. Discursively, they devalue women’s ability to make an informed abortion decision. Materially, there is not significant evidence that they impact abortion access.Lastly, I consider pre-abortion ultrasound viewing laws. Twenty-five states currently legislate the pre-abortion ultrasound, with 6 mandating that the woman be presented with the image of her ultrasound. In my research, I’ve found that, despite the stated hopes of abortion opponents, viewing the ultrasound does not change women’s minds about abortion. Materially, women’s access to care is not substantially reduced by this regulation, but we might nonetheless identify this legislation as discursively devaluing women’s autonomy in abortion decision-making.

Of these four common restrictions, the first two, in practice, impede women’s access to abortion care. The third and fourth may have troubling discursive implications about women’s autonomy, but there is no evidence that they directly circumscribe women’s ability to obtain an abortion.

This is not to say that only some restrictions matter. Laws that discursively devalue women’s decision-making are not innocuous. Their frequency underscores how law produces and reproduces gender (e.g., implicitly presuming that women make decisions capriciously) and should prompt us to think about restrictions not only for their material effects but also for how they contribute to gender inequality far beyond abortion debates.

A Right Turn and a New Era

by Drew Halfmann

The recent controversy over trumped-up claims that Planned Parenthood “sells baby parts” has caused many to wonder if we are entering a new era of abortion politics and policy. A new era is indeed upon us, but the attacks on Planned Parenthood are neither the main symptom nor the cause. Instead, the key marker is the enactment of significant new state restrictions on abortion providers—the result of the Republican Party’s three-decades long drift to the right and its particularly hard right turn since the rise of the Tea Party in 2009.

The recent controversy is not much of a departure. Though hidden-camera Internet videos are a fairly new tactic, anti-abortion activists have tried to de-fund Planned Parenthood since the Reagan era, and they’ve distributed grotesque abortion images for even longer. Significant defunding of Planned Parenthood seems unlikely in the near future, though. The vast majority of the organization’s federal funding comes from Medicaid. Cuts to this funding at the federal level will require the election of a Republican president, and state attempts to cancel Planned Parenthood’s Medicaid contracts have been overturned by federal courts. Planned Parenthood’s public approval ratings have declined since the 1990s, but most of this change has occurred among Republicans. Its ratings have barely moved during the recent controversy and remain much higher than those of Congress.

The latest controversy is also unlikely to change public attitudes about abortion. Most Americans believe that abortion should be legal, but subject to some restrictions, and most measures of abortion attitudes have remained stable since Roe v. Wade. Though the parties have polarized on abortion, the public has not. More importantly, public opinion is not the key determinant of changes in abortion policy. For most voters, abortion is not a central issue; elections are determined mainly by issues such as economic growth. The key driver of abortion policy, then, is the election of Republicans and the continued rightward movement of the GOP.

At the time of Roe v. Wade, the two parties were not clearly divided over the abortion issue. But in the late 1970s, anti-abortion activists, the New Right, and the Christian Right gained influence in the Republican Party. During the 1980s, Republican presidents made several Supreme Court nominations that resulted in the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision that gave Congress and the states more leeway to regulate abortion. In the years since, Republican state legislatures have enacted a host of abortion restrictions, and the number and effectiveness of those restrictions has increased dramatically in recent years. The most effective have applied surgical center regulations to abortion clinics and required clinics to obtain admitting privileges from hostile local hospitals. As Katrina Kimport notes in her piece, in Texas, such restrictions have reduced the number of abortion clinics from 36 to 10 since 2010.What caused the GOP’s rightward turn? The most promising explanations involve the ability of rich individuals and social movements, such as the Christian Right and the Tea Party, to use money, labor, and votes in low-turnout caucuses and elections to nominate candidates who move the party away from the center. In addition, the rising incomes of the top 1% have increased their ability to fund the GOP; partisan media and the Internet have made it easier for party activists to monitor and discipline RINOs (their sneering term for “Republicans In Name Only”); and low-information voters, who used to swing between the parties because they couldn’t tell them apart, have noticed the increasing difference and stopped swinging. Candidates no longer fight over undecided voters, but instead focus on mobilizing their base to vote.

The abortion stakes in the 2016 election will be high.The next president may have multiple opportunities to change the direction of the Supreme Court—Justice Scalia’s seat remains open, three Justices are 80 years old or close to it (Democrats Ginsburg and Breyer and Republican Kennedy), and Kennedy is the swing voter on a closely divided Court. Meanwhile, the Court recently announced that it will consider the Texas abortion restrictions this term, its first abortion case in eight years, and could deliver its opinion just weeks before the election.

The Emergence of The Black Fetus

by Kimala Price

Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson came under fire for his controversial remarks about abortion and African Americans when, in an interview on Meet the Press, he equated the abortion of Black fetuses to slavery, and in an interview on FOX News, he said, “I know who Margaret Sanger [the founder of Planned Parenthood] is, and I know that she believed in eugenics and that she was not particularly enamored with Black people. And one of the reasons that you find most of their clinics in Black neighborhoods is so that you [sic] can find a way to control that population.” But Carson is not alone in making these claims. The anti-abortion group Protecting Black Life argues that Planned Parenthood “has located 79% of its surgical abortion facilities within walking distance of African American or Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods” as a means to decrease the African-American population. These sentiments are reflective of a racialized rhetoric that has taken hold within the anti-abortion movement in the United States.

A network of anti-abortion groups, including several founded and led by African Americans, has launched an issue campaign that argues that African Americans are facing a “Black genocide” at the hands of abortion providers. For example, the Radiance Foundation has developed a nationwide billboard ad campaign that features photo images of African-American infants and small children with provocative captions such as “Black Children Are an Endangered Species” and “The Most Dangerous Place for an African American Is in the Womb.” These ads first appeared in 2010 in Atlanta, Georgia. Other groups, such as LEARN Northeast, have created websites, including toomanyaborted.com, blackgenocide.org, and protectingblacklife.org, that explicitly make the “abortion is Black genocide” argument. The Texas-based group Life Dynamics has produced and distributed a film entitled Maafa 21: Black Genocide in the 21st Century which has enjoyed public screenings on the campuses of historically Black colleges and universities and at African-American community centers and churches across the nation.

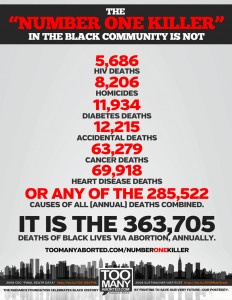

The Black genocide assertions are based on the fact that African-American women have disproportionately higher rates of abortion than White women and Latinas. Indeed, the abortion rate for African-American women (29.7 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44 years) is close to four times that for White women (8.0 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44 years), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Moreover, the Guttmacher Institute reports that 30% of all abortions are obtained by African-American women. Although few will dispute these statistics, it is the interpretation of those facts that is at issue. Reproductive justice activists argue that these statistics are indicative of the overall health disparities that African-American women (and other women of color) face, including higher rates of unintended pregnancies. These disparities are in part due to difficulty in obtaining high-quality contraceptive services, the lack of access to adequate health care in general, and the overall lack of economic and social equality. In contrast, anti-abortion groups argue that these statistics are proof that there is a conspiracy among social, political, and economic elites to reduce the population of African Americans.Through this campaign, we are witnessing the public emergence of the “Black Fetus.” The fetus has always played a central role in the political rhetoric of the anti-abortion movement; however, it generally has remained “race-less.” Because the construct of race depends upon physical markers such as skin color and facial features in order to be salient, one strategy to convey “race” or “blackness” is the use of images of infants or small children instead of the now-iconic ultrasound images of fetuses in utero. Another strategy is constructing a narrative that relies on three rhetorical moves: the cultivation of racialized anxiety through assertions that abortion is “the number one killer of African Americans,” accusations of racial betrayal directed toward key African-American leaders and organizations (e.g., Barack Obama and the NAACP) that have publically supported abortion and reproductive rights; and the exploitation of a collective historical mistrust of medical institutions within African-American communities. This narrative also attempts to evoke strong emotional responses by frequently referencing Martin Luther King, Jr. and making comparisons to civil rights and slavery.

Ultimately, this discourse implicitly pits the personal reproductive decisions of individual African-American women against the perceived collective goals and needs of the African-American community. The implication is that African-American women are unwitting contributors to racial genocide if they decide to obtain abortions. This is a racialized, gendered sexual politics that attempts to shame, silence, and coerce African-American women into compliance with a conservative political agenda.

Politics and Planned Parenthood

by Deana A. Rohlinger

Planned Parenthood found itself caught in the middle of a political maelstrom last fall after the pro-life group, Center for Medical Progress, released a video that allegedly showed the organization selling fetal body parts for profit. Republicans called for the immediate defunding of the health organization and Republican presidential hopefuls chimed in, accusing Planned Parenthood of “profiting” off of abortion procedures. Former Texas governor Rick Perry said “The video showing a Planned Parenthood employee selling the body parts of aborted children is a disturbing reminder of the organization’s penchant for profiting off the tragedy of a destroyed human life.” Several states have since made moves to defund (or have already defunded) the organization and, in September, the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee held hearings regarding its tax-payer funding. Outgoing House Speaker John Boehner appointed eight Republicans to a committee charged with investigating the group’s practices.These attacks on Planned Parenthood’s funding are not new. Republicans periodically seek to cut off the organization’s revenue, despite the fact that federal dollars are not used to pay for abortions. These efforts are, in part, an attempt to appease pro-life activists, who use a candidate’s commitment to the cause as a litmus test for their votes. As access to abortion has tightened at the local and state level, Republicans find it increasingly difficult to prove their commitment to pro-life loyalists.Now, of course, Republicans are dealing with the consequences of their success.

The last frontiers of the war are making abortion virtually illegal—an idea that the debate over personhood legislation revealed is not universally popular, even among Republicans—and dismantling Planned Parenthood.

The attack on Planned Parenthood reveals three troubling trends in American politics. First, there is a startling disconnect between knowledge and action. While politicians from both parties speak first and research later, the comments made by Republicans illustrated a clear lack of knowledge about women’s health issues and Planned Parenthood’s mission, services, and funding. Presidential candidate Donald Trump described Planned Parenthood as an “abortion factory,” while Texas’s Lt. Governor Dan Patrick characterized it as a “referral service” that does little more than “profit from killing babies and then selling body parts of those aborted babies.” Republicans are pushing to suspend Planned Parenthood’s funding for a year so that they can “investigate” the organization.

Second, while didactic rhetoric and grand gestures make for great news coverage, journalists seem increasingly unwilling to bring clarity to the abortion issue beyond the editorial pages. As news media are considered the fourth leg of government, the remarkable shallowness in coverage is problematic.

Finally, political calculation completely trumps party values. Notice that Democrats did not exactly run to Planned Parenthood’s aid this summer, even though they have publicly supported the organization’s focus on women’s health in the past. Consider former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s response to the lightning rod video: more than three weeks of silence. When she finally commented to a reporter from the New Hampshire Union Leader, Clinton reluctantly said that some of the images were “disturbing” and that the video pointed to problems in “the process,” but not with the organization. As I discussed in an earlier Contexts piece, this middling non-response should be understood as the new normal for Democratic politicians; today, women’s rights are pitted directly against religious rights, and Democrats don’t want to get caught on the least popular side of the debate.

In the short term, Planned Parenthood is unlikely to be defunded, at least by the federal government. States, however, are a different matter. Texas, which already defunded the organization, subpoenaed Planned Parenthood clinics for information regarding patients and employees as part of an investigation of fetal tissue transactions. In the long term, Planned Parenthood should prepare for a public relations battle with political and financial consequences. Sure, the long-standing organization has faced other public controversies. The difference here is that an organizational representative looked bad in the context of the work Planned Parenthood conducts. This time, even pro-choice advocates were nervous that the group had been up to no good. A recent Gallup Poll shows that only 59% of respondents view the organization favorably—down 22% from 1993. If these attacks continue, Planned Parenthood may be left with very few allies on either side of the aisle.