Tobacco 21

Although smoking rates have declined significantly in the United States over the past several decades, the Office of the Surgeon General noted in a 2014 report that the public health burden of tobacco use remains high, especially in subpopulations of lower socioeconomic status. Research on tobacco control program and policy efforts has demonstrated that a comprehensive approach is needed, including, as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, interventions aimed at knowledge/attitudes, increased cost through taxation, youth access restrictions, environmental exposure reduction, and cessation.

In 2005, Needham, Massachusetts became the first jurisdiction in the U.S. to raise the age of legal access to tobacco products to 21 years. As of January 1, 2018, over 280 cities/counties and 5 states have implemented similar laws, and numerous other state and local governments are currently considering this policy, outlined at tobacco21.org. “Tobacco 21,” as it is called in public health and advocacy circles, is now a top policy priority in tobacco control, with endorsements from the American Medical Association, the American Pediatric Association, and the American Public Health Association. Despite widespread support and rapid diffusion, this policy is not without some concerns, including a lack of empirical evidence regarding its public health impact, and many have worries about what they see as an extension of government paternalism.

The Policy

Tobacco 21 is a type of youth access “PUP law”—a policy that focuses on the legal age for purchase, use, and/or possession of tobacco. Before 1992, local and state PUP laws and consequences varied, but in that year, an amendment to the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration Reorganization Act (PL 102-321) requested that all states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and U.S. territories enact and enforce laws that prohibit the sale or distribution of tobacco products to those under age 18. Jurisdictions must demonstrate compliance with these “Synar Amendment” regulations in order to receive their full Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant awards, a large carrot attached to an effective regulatory stick (see my coauthored 2000 Tobacco Control article for a review of this and other anti-tobacco initiatives aimed at youth).The Synar Amendment led to every state enacting 18 as the minimum legal age for tobacco sales/distribution, but current federal law also prevents the federal government from raising the legal age any higher. Effectively, any PUP policy above the age of 18 can only occur at the state and local level. With some variation, the majority of current local and state jurisdictions with Tobacco 21 laws have implemented a policy with the following provisions:

- Retailers/distributors are prohibited from selling or giving tobacco products to anyone under age 21.

- The use or possession of tobacco products by 18-20 year olds is not prohibited. Under most Tobacco 21 policies, a young adult under age 21 can legally smoke and openly possess tobacco; he/she cannot purchase or receive tobacco from a retailer or distributor.

- Legal consequences are aimed at the retailer/distributer and generally include fines that increase in severity with repeated violations, ultimately resulting in revocation of a license to sell tobacco.

- Electronic-nicotine delivery systems are defined as “tobacco products” and also covered by the law.

The Research Evidence

Tobacco 21 is a public policy that has been spreading quickly without an empirical evidence base. To date, there have been no experimental or time-series studies of its impact in the U.S. or elsewhere. While much can be learned from the significant body of social science and policy research on the impact of raising the legal age to purchase, use, and possess alcohol, Tobacco 21 targets a very different risk behavior, one without immediate negative outcomes or significant externalities such as impaired driving. At its core, increasing the alcohol legal access age to 21 is a public policy attempting to protect people from others (in regard to higher rates of impaired driving among young adults), while Tobacco 21 is a policy attempting to protect young adults and adolescents from themselves.

As reported in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 2016, there has been only one study of a Tobacco 21 policy to date: A quasi-experimental evaluation of the 2005 Needham ordinance reported a 47% decline in smoking among high school students after implementation, based self-reported data from area high school students. This research suffers from some weaknesses, including that Needham simultaneously implemented additional anti-smoking activities along with the Tobacco 21 policy and that the study did not address the impact on 18-20 year olds. In addition, caution is needed when generalizing public policy results from a small, racially homogenous and wealthy Boston suburb to other populations and jurisdictions.

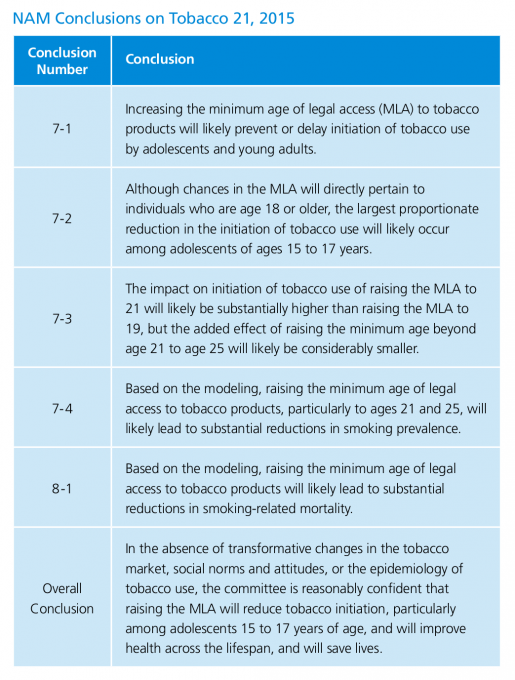

In 2015, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) released a consensus study titled “Public Health Implications of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products.” In it, a committee of scientists, policy experts, and public health practitioners (including myself) reviewed the existing research literature and conducted population-based simulation modeling with the aim of providing scientific consensus on the likely public health implications of raising the tobacco legal access age. The major findings, outlined in the table below, suggested that raising the legal age to 21 would likely lead to a small yet significant decrease in tobacco use among 15-17 year olds, primarily because they would have a harder time passing for the legal age and getting tobacco from slightly older friends. Simulation modeling estimated that cohorts exposed to this policy from birth would likely experience a 12% decline in smoking rates and 10% decline in smoking-related mortality over the lifecourse.

The NAM committee’s conclusion that the key behavioral impact of this policy would be on 15-17 year olds rather than young adults was based on a large amount of social science and epidemiological research, including several studies demonstrating that the primary ways in which adolescents gain access to tobacco is through social sources and by purchasing it themselves. By increasing barriers to adolescent access, the probable result is a small decrease in smoking initiation, which in turn would lead to public health benefits among cohorts of youth exposed to this policy.

Moving Forward

Public opinion data cited in the aforementioned NEJM article reveal that approximately three-fourths of U.S. adults—including the majority of current smokers—strongly support raising the minimum age of tobacco sales to 21 years. Public support likely rests heavily on the assumption that this policy will have a positive impact on public health, which is not unreasonable. Based on the limited research to date, it is quite probable that the public policy of Tobacco 21 will have a positive health impact, primarily through its impact on the smoking behavior of 15-17 year olds. Because the health risks from smoking are many and significant, small changes in adolescent smoking behavior have significant population-level effects over time. Public health gains from effective tobacco control will be seen primarily in populations with lower levels of income and education, given their relatively higher rates of smoking.

Nonetheless, at this time, there is no empirical evaluation research evidence outside of policy simulation modeling to support claims made about the direction or magnitude of public health gains resulting from Tobacco 21 policy efforts The degree to which Tobacco 21 is enforced and any counter measures by the tobacco industry are among potential countervailing forces that could have an impact on overall policy effectiveness.

Further, even if Tobacco 21 does result in positive public health benefits, this alone is not sufficient to justify and promote its further diffusion. Along with benefits, public policies also have costs and burdens that are often unequally distributed across subpopulations within society. Young adults can legally get married, serve in the military, purchase property, and make a plethora of other adult decisions; nonetheless, Tobacco 21 would prohibit them from purchasing (but not using) tobacco products. In addition, as both the Office of the Surgeon General and our NAM committee note, smoking rates are significantly higher among young adults ages 18-20 years who did not graduate from high school or pursue post-secondary education. As such, this policy places behavioral restrictions/burdens on 18- to 20-year-olds of lower socioeconomic position who are also more likely to be working full-time, serving in the military, living independently, and engaging in other putative “adult” behaviors.

Increasing the legal age of tobacco access to 21 has been criticized as paternalistic by many individuals and organizations. The growth in public policies that infringe upon personal behaviors and choices that are not related to infectious disease or otherwise do not directly affect others has fueled “nanny state” concerns and narratives. Some view Tobacco 21 in the same paternalistic light as other public health policies that restrict adult personal choice, such as mandatory helmet laws, regulatory limits on restaurant portion sizes, bans on trans fats, and sugar-sweetened beverage taxes.

Every public policy has benefits and burdens; considering the fairness of the distribution of benefits and burdens on those effected by the policy is a standard part of policy analysis. In the case of Tobacco 21, the burdens of the policy fall primarily on 18- to 20-year-olds who can legally engage in most other activities and decisions of adults, while the benefits accrue to younger teenagers who will experience constraints on access to tobacco and decrease initiation and use as a result.

Evaluation research is clearly needed on the population- and sub-population effects of Tobacco 21 on behavioral and health outcomes. As a policy phenomenon, Tobacco 21 lends itself to rigorous evaluation as a natural experiment. Given the large number of jurisdictions that have implemented very similar policies and the availability of solid population data on tobacco sales and behavior in many jurisdictions, multiple time-series analyses can be conducted to exploit variation in the timing of the policy implementation.

There is also a need for sociological inquiry on other aspects of this rapidly diffusing policy. First, there is a great need for qualitative research on how adolescents and young adults view, interpret, and navigate this policy, including by socioeconomic position, race/ethnicity, age, and place. This includes investigation into how young adults ages 18-20 view Tobacco 21 and its benefits/burdens in the context of their more general perceptions about the government. Second, research regarding how Tobacco 21 interacts with other tobacco-related policies, interventions, and trends, including decisions by retail chain stores to no longer sell tobacco, will be instructive to policymakers and scholars. Finally, mixed-method research regarding perceptions and opinions about government paternalism (the “nanny state”) and the increased political and ideological polarization in the U.S. is needed. This, however, needs to be done in the context of “tobacco exceptionalism” or the perspective that restrictive and/or paternalistic tobacco control policies—including Tobacco 21—are justified because tobacco use is “different” than other health risk behaviors, given its tremendous and unequivocal public health burden.