From The Case for Loving, by Selina Alko with illustrations by Sean Qualls.

Virginia is for Lovers

Love is hard to argue with, its demands absolute, its yearnings seemingly colorblind. But Virginia fought hard against love, going so far to as to arrest it, charge it with a felony, sentence it to a year in jail, and then exile it to a neighboring city. And so love sued Virginia and took it to the Supreme Court and won.

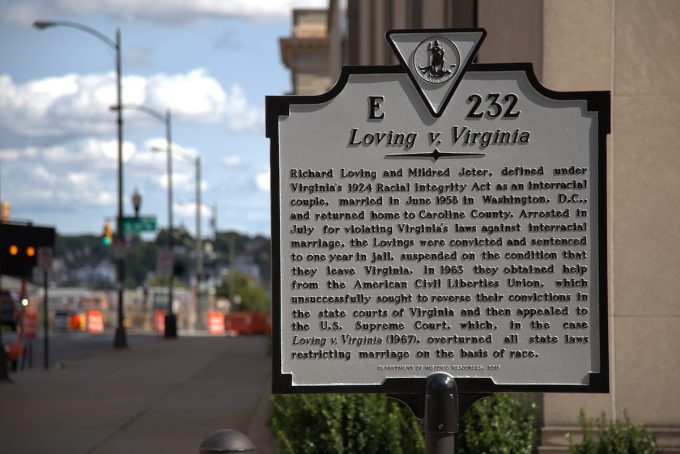

I’m referring of course to Loving v. Virginia, the fifty-year-old landmark civil rights decision that invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage. The case was brought by non-White (more on that in a moment) Mildred Loving (formerly Jeter) and Richard Loving, a White man. Their marriage (performed in Washington, D.C.) violated their home state’s anti-miscegenation statute, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. Sentiment might have its place, Virginia argued, but it had to obey the order of things. As the sentencing judge, Leon M. Bazile argued in 1965: “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

The Lovings, supported by the ACLU, appealed the state-level decision to the Supreme Court, which unanimously overturned their convictions in 1967. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in his opinion that “The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination.” Thus did the Lovings become accidental activists, and with their victory laws barring interracial marriage with Blacks in Virginia and 15 other states came tumbling down. Today, one in six newlyweds in the United States has a spouse of a different race.

And yet, the legacy of Loving remains complex. First, Angela Gonzales and Peter Wallenstein look at the Black and White divide in 20th century Virginia and reveal that Mildred Loving didn’t think of herself as Black. Gonzales shows how officials in Virginia and throughout the Southeast actively worked to erase “Indian” or “Native Virginian” identities in deference to White supremacy, while Wallenstein delves more deeply into legal fights over anti-miscegenation laws and the challenges posed by the lasting rhetoric of race. Gretchen Livingston picks up with data on the status of interracial marriage in the U.S. today, and Christopher Bonastia finds cause for optimism in those numbers in a time when “unvarnished, unapologetic racism has made an ignoble comeback.” Where laws against discrimination have been left weakly enforced—if at all—the simple victory represented by the Loving case helps us believe that, well, Virginia and the United States are still for lovers. shehzad nadeem

- Intermarriage, 50 Years On, by Gretchen Livingston

- The Binds of Racial Binaries, by Peter Wallenstein

- Loving and the Legacy of Indian Removal, by Angela Gonzales

- Easy Loving?, by Christopher Bonastia

Intermarriage, 50 Years On

by Gretchen Livingston

A half-century ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that marriage across racial lines was legal throughout the country. Until this ruling, interracial marriages were forbidden in many states.

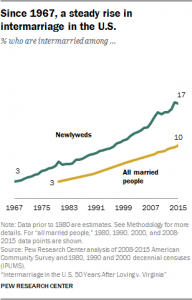

Fifty years on, how have things changed? In 1967, about 3% of newlywed couples in the U.S. were intermarried—meaning they included either two spouses of different races or one Hispanic and one non-Hispanic spouse. By 1980, that share had about doubled to 7% and in 2015, 17% of all newlywed couples in the U.S. were intermarried. More broadly, 10% of all married couples in the U.S.—regardless of how long ago they may have wed—now include spouses of different races, or one Hispanic and one non-Hispanic spouse.

Asian and Hispanic newlyweds are by far the most likely to intermarry—close to 3-in-10 of each group do so. In comparison, 18% of Black newlyweds and 11% of White newlyweds are intermarried, marking a dramatic increase from 1980 (when just 5% of Black newlyweds and 4% of White newlyweds were).

Whether the changes in intermarriage over the last 50 years have been remarkably rapid or have occurred at a snail’s pace is a matter of perspective. What seems clear, though, is that they are linked, in part, to the increasing racial and ethnic diversity of the country, as well as shifting attitudes about race.

The “marriage market,” defined here as adults who are either unmarried or who married in the past year, reflects this growing diversity. Since 1980, the share of Whites in this group has declined by 18 percentage points, down to 59%, while the shares of Hispanics and Asians have grown by 11 and 3 percentage points, respectively. The share of Blacks in the marriage market has remained more or less constant, at around 15%. Similar compositional changes have occurred among U.S. newlyweds, as well.

The changing racial and ethnic profile of the nation likely drives increases in intermarriage via a couple of mechanisms. First, as the share of newlyweds who are Hispanic or Asian (and who are more likely to intermarry) grows, and the share of White newlyweds (who are less likely to intermarry) declines, the overall share of U.S. newlyweds who are intermarried will rise, simply as a result of the compositional change.

Second, the increasing variation in the racial and ethnic makeup of the U.S. marriage market means that on average there is an increasing chance that people will find partners of a different race or ethnicity, based on sheer numbers alone. This association plays out in terms of long-term trend and across many metro areas, as well: For instance, in Honolulu, which is extremely diverse, 42% of newlyweds are intermarried, while in Asheville, where 85% of the marriage market is White, just 3% are.

Of course, intermarriage is not based purely on demographics. Rates have more than tripled among Black newlyweds, despite the fact that their share of the marriage market has remained stable since 1980. And some metro areas that aren’t particularly diverse have relatively high rates of intermarriage: Fayetteville, North Carolina, where 29% of newlyweds are intermarried, is an example. (In this case, the large military presence—often associated with more intermarriage—may be playing a role.) At the same time, some metros that are relatively diverse still have extremely low rates of intermarriage. Jackson, Mississippi, for instance, has a newlywed intermarriage rate (3%) similar to Asheville, despite the fact that its marriage market includes a sizeable share of both Blacks (61%) and Whites (36%).

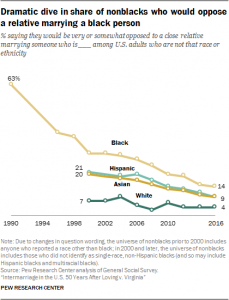

Variations in attitudes may explain some of the disconnect between racial and ethnic composition and actual intermarriage rates: As recently as 1990, the majority of non-Black adults in the U.S. (63%) said that they would be somewhat or very upset if a close relative married a Black person, according to the General Social Survey. Flash forward to 2017, and the share saying as much has dropped to 14%. There have been declines in the shares of adults who oppose a close relative intermarrying someone who is Hispanic, Asian, or White, as well.

More broadly, the share of adults who say more people of different races marrying each other generally is a good thing for our society has increased markedly, from 24% in 2010 to 39% in 2017, while the share who says this is a bad thing has ticked down and now stands at 9%. (Notably, the largest share of adult respondents—52%—report that more intermarriage doesn’t make much difference for our society.)

While opposition to intermarriage has been declining in the U.S., attitudinal differences persist across groups. About one-in-five (18%) Black adults say that more people of different races marrying each other generally is a bad thing for our society, compared with 9% of Whites and 3% of Hispanics. Differences emerge by age, education, community type, and political party affiliation as well: Older people, those with a high school diploma or less, those living in rural areas, and those who identify as Republican or lean Republican are all more likely to say that more intermarriage is generally a bad thing for our society.

J.J. Prats via Historic Marker Database

The Binds of Racial Binaries

by Peter Wallenstein

When the Department of Historic Resources (DHR) of Virginia first announced a 50th anniversary commemorative site for the Loving v Virginia case, it was to be located in the couple’s native Caroline County, not in Richmond, where a historical marker was eventually dedicated. The Richmond site abuts a former home of the Virginia Supreme Court, which had ruled against the Lovings, prompting the appeal that took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court, so it made sense, but the move was actually motivated by a family dispute.

The site had to be switched because of the conflict outlined in Angela Gonzales’ piece in this suite of viewpoints: At least one descendant insisted that Mildred Loving be identified as “a Rappahannock Indian” erroneously “identified by the Commonwealth as African American.” When consulted by the DHR, I urged that the couple be identified as being “defined under Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act as an interracial couple,” language the DHR adopted. But from the Loving family came word that the change did not satisfy, and especially when county authorities accepted that position, the marker had to find a different home.

Writers—historians, journalists—almost invariably cast the couple as Richard, “White,” and Mildred, “Black” or “African American,” much as accounts of her death in 2008 did. Mildred had described herself on her 1958 marriage license as “Indian” and, in a letter seeking legal help in 1963, as “part negro, and part indian.” As the story unfolded it became clear that Mildred’s sole surviving child, Peggy, accepted the DHR’s modified language and wished for a historical marker to be located in Caroline County, while Peggy’s son Mark stood his ground. In effect, Mildred’s grandson, nearly six decades later, insisted upon Mildred’s first declaration of race and rejected the second. He exemplified a wish to maintain control of the family’s story, having seen it misappropriated in the past, and the only alternative seemed to require an effort to curtail its being told at all.

After the unveiling of the Richmond marker, Peggy convinced Caroline County authorities to reverse their earlier decision and approve a marker for the original site. New language, approved four months after the Richmond event, presented the couple as being “of different racial backgrounds.” Thus it bypassed any explicit rendering of Mildred as African American or Native American or both.

As the struggle over Mildred Loving’s racial identity demonstrates, people are not readily divided into “Black” and “White”—or, if they are, the language masks or distorts and, regardless, can be disputed. So the rhetoric attached to perceptions of identity resonates nearly a century after the 1924 Racial Integrity Act’s reductive categorization of “white” and “colored” (widely understood as a proxy for “Black,” a category defined in 1924 according to a “one-drop” rule of Black racial identity).

Even though these definitions have lost their power to mean the difference between a typical marriage and exile or a term in prison as a consequence of it, the language and constructs of race still challenge Americans. Great change has taken place, to be sure. The rural society of Caroline County in the 1950s made some space for an interracial couple to be together, if not to marry. These many years later, couples defined as “interracial” find ample room to marry, without legal obstacle or penalty, anywhere in America. And ever-larger numbers of interracial couples choose to do so. During most of the half-century after Loving v. Virginia, rates of “interracial” marriage showed modest increases, both in the states where such marriages had long been legal and in those where Loving overturned racial restrictions.

Before the Lovings, there was the 1940s legal dispute regarding a California woman, Andrea Perez, who was of Mexican descent. Perez, classified in that time and place as White, and Sylvester Davis, classified as Black, won the right to marry in a 4–3 state Supreme Court decision that threw out California’s miscegenation laws. It was another “Black and White” moment, whatever the couple’s own racial identifications.

In 2012 a Pew report, “The Rise of Intermarriage,” newly married people were divided into “white,” “black,” “Asian,” and “Hispanic,” so that intermarried couples were classified as either “interracial” or, if involving only one Latino, “interethnic.” The new data showed considerable increases in “intermarriage,” not only “interracial” marriages between a “white” person and an “Asian” but also, at last, couples that included a “black” person and someone “white.”

Still, the very racial constructs Pew adopted are as problematic and anachronistic as those that constricted Mildred Loving and Andrea Perez. For Pew, the category “white” included people of Irish, Greek, and Italian ancestry, among other groups whose “white” racial identity was not too distantly contested by Anglo/Protestant Whites. “Black” could include people from the Caribbean and immigrants from Africa as well as African Americans. “Asian” included people of Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Filipino, and Korean ancestry—though in an earlier time these groups might well have viewed each other with disdain and hostility, not as members of a shared “racial” (or pan-ethnic) Asian-American identity.

Whatever the constructs, whatever the rhetoric, the Pew Report demonstrates a long-term alteration in marriage behavior among Americans turned loose by Loving v. Virginia. This is true even if the task of calibrating those changes can mask the change in the act of clarifying it, and even though Loving could not operate alone, as shifts in racial terms in the choice of a marital partner depended in large part, too, on a changing culture and society, including considerable desegregation in schools, employment, and housing.

But the contest over Mildred Loving’s racial identity—explicit in Virginia in 2017, implicit in the continuing classification of her in simple binary terms as “Black” because she was not “White”—reveals how the present carries on the past. The Black-White binary persists, both in cultural shorthand and in broad understanding of racial matters.

Loving and the Legacy of Indian Removal

by Angela Gonzales

To mark the 50th anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court case, Loving v. Virginia, the State of Virginia planned to erect a highway marker in honor of the couple made famous by the case. The planned inscription for the marker read: “Richard Loving, a white man, and Mildred Jeter, a woman of African-American and Virginia Indian descent married in June 1958 in Washington D.C.” But much like the controversy surrounding the case fifty years before, discord erupted shortly after the text for the planned inscription was made public. The Lovings’ grandson, Mark Loving, objected to language identifying his grandmother as having African-American ancestry, stating that Mildred was “all Virginia Indian.” Indeed, in one of her final interviews, Mildred Loving declared in 2004: “I am not Black. I have no Black ancestry. I am Indian—Rappahannock.”

Mildred’s negation of Black ancestry and declaration as American Indian stand in contrast to how she was portrayed at the time of the case and how she is remembered today. For most people, Mildred was Black, an identity firmly established by the U.S. Supreme Court case that bears her name. Her claim to the contrary and our insistence or resistance to her being Black, Indian, or both are evidence of the enduring legacy of eugenics in how we think about race and identity and our historical amnesia about the colonization of the Native people of Virginia.

Native people of Virginia, and indeed in much of the Southeast, provide an important example of how White supremacy and eugenics-informed public policy during the first quarter of the 20th century systematically erased Native people and communities from official records. Informed by 18th and 19th century ideologies about “race” and “racial superiority”, eugenics emerged through the work of Francis Galton, younger cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton was deeply influenced by the work of his cousin, particularly in the area of animal breeding and its implications for assessing the genetic variation and value in the human population. Through a kind of bloodline arithmetic, Galton championed the intergenerational transmission of race and racial attributes through the division of “pure” racial blood over generations. He developed a fractional concept of racial inheritance whereby successive generations inherited one-half of their racial blood from parents, one-quarter from grandparents, and so on. Not all blood was created equal, of course, and Galton’s concern was for preserving and promoting “the more suitable races or strains of blood.”

In Virginia and elsewhere in the United States, the fractional concept of racial inheritance gained traction, eventually giving rise to race codes for both Blacks and Indians. In 1866, the State of Virginia declared that “[e]very person having one-fourth or more Negro blood shall be deemed a colored person, and every person not a colored person having one-fourth or more Indian blood shall be deemed an Indian.” This conception of racial inheritance formed the basis of the “one-drop rule” defining anyone with any known or putative Black ancestry unequivocally Black and a lexicon that quantified the amount: “mulatto,” “quadroon,” and “octoroon.” But where Black identity was based on any fraction of Black blood, Indian identity required a greater fraction of Indian blood, usually one-quarter or more. Rooted in an ideology of racial purity, the concept of fractional inheritance served to not only dispossess the Native peoples of Virginia of their land but of their very identity as Indian. What warfare and disease failed to accomplish, arithmetic and science took care of by effecting the “statistical genocide” of the Native people of Virginia.

More than 500 years of colonization had decimated Native peoples and nations throughout the Southeast, rendering them then both invisible and divisible to a society who refused to recognize them as anything other than Black. Within this context, the Native people of Virginia became the target of the state’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924.

Passed on March 20, 1924 by the Virginia General Assembly, the Racial Integrity Act strictly prohibited interracial relationships. Instated largely through the lobbying efforts of Walter Plecker, Registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics from 1912 to 1942, the Act also made a clear legal definition of a White person as one “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.” However, it provided a special exception—the “Pocahontas exception”—to protect the racial status of many of Virginia’s leading families. These descendants of Pocahontas and John Rolfe inspired an allowance: “persons who have one-sixteenth or less American Indian blood and have no other non-Caucasic blood” could be defined as White.

Plecker did not believe that there were any “pure” Indians left in Virginia and that the Pocahontas exception was allowing people of mixed Indian-Black ancestry to pass as White. Using the weight of his office, Plecker enjoined town clerks throughout Virginia to classify anyone claiming to be Indian as Black. He also sent letters to Virginia’s town and county clerks, as well as to physicians, nurses, and school administrators warning that those seeking to identify as Indians were frauds and criminals: “Now that these people are playing up the advantages gained by being permitted to give ‘Indian’ as the race of the child’s parents on birth certificates, we see the great mistake made in not stopping earlier the organized propagation of this racial falsehood…. Some of these mongrels, finding that they have been able to sneak in their birth certificates unchallenged as Indians are now making a rush to register as white.”

Plecker even took it upon himself to alter birth certificates issued to Indians before 1924 (when the Racial Integrity Act was implemented), qualifying them with the inscription, “The early records of this State show this group of people are descendants of free negroes…. Under the law of Virginia, [subject] is, therefore, classified as a colored person.”

Plecker’s alterations and his appeals in the form of pamphlets, newspaper editorials, and direct correspondence with local officials proved effective. In 1930, the U.S. Census indicated that there were 779 American Indians living in Virginia. By 1940, the figure had dropped to 198. For all intents and purposes, when it came to matters of births, marriages, and deaths, the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics was empowered to decide the race of every Virginian and, in so doing, effectively erased the Native people of Virginia from all official records .

On June 12, 2017, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe unveiled the state historical marker commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia. The controversy over the inscription was resolved by eliminating any racial designations and simply identified Richard and Mildred Loving as an “interracial couple.” For many, the inscription affirms the right to marry regardless of race, but for the descendants of Mildred Loving and the Native peoples of Virginia it serves as a reminder of the legacy of eugenics that continues to deny their identity as Indian. It is only through the erasure of Native Virginian identities that we celebrate Loving as a Black and White victory.

Easy Loving?

by Christopher Bonastia

It’s hard to say a begrudging word about Richard and Mildred Loving. Myself a White man married to a Black woman, I find their story moving for obvious reasons. At the same time, I am troubled by their veneration as civil rights heroes over lesser-known freedom fighters such as Gloria Richardson, who led a multi-faceted campaign for racial justice in Cambridge, Maryland, Reverend L. Francis Griffin, who fought for the resumption of public education in Prince Edward County, Virginia, and …this list could go on for several paragraphs. While their tactics and personalities varied, what bound these individuals was their unapologetic demand for citizenship and equality for all Black Americans. They were activists, and proudly so.

Virtually every portrayal of the Lovings depicts them as humble country folk, accidental history-makers who simply wanted to live in peace as a married couple. They are to be commended for willing to take their fight to court, enduring publicity they clearly did not want. And yet the appeal of their story is in part due to the couple’s image as “non-activists”: everyday people who don’t wish to stir up trouble. But sometimes trouble is exactly what is needed. As civil rights hero and long-time U.S. Representative John Lewis counsels young people: “You must find a way to get in the way and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

The Lovings’ fight to strike down laws banning interracial marriage, and how that effort compares to other battles for racial equality, is also worth pondering. On the one hand, marriage is perhaps the most intimate form of interracial contact, and thus its potential legalization—by preventing states from banning it—drew condemnation from racists worried about a “mongrel race,” or more specifically, their White children marrying Black partners and producing non-White grandchildren. On the other hand, the resulting legal change was essentially costless for both government and most individual families.

Compare this to more structural policy changes. To those who opposed it, a rigorous program of school desegregation augured chaos in the classroom, ballooning transportation costs, physical danger, the destruction of the neighborhood school—and increased interracial intimacy at an impressionable age. Neighborhood desegregation would threaten property values, supposedly bring a wave of crime and ever-closer contact with Blacks. Ending employment discrimination might jeopardize the livelihoods of White workers, no longer protected by an artificially delimited job market. And affirmative action brought fears that purportedly less-qualified Blacks and Latino/as would jump the line for hiring and promotion.

Because the 1967 Loving decision touched few of its opponents directly, it provoked less social turmoil than even the desegregation of public swimming pools. Consider Atlanta, where a 1960 study had found that 42 of the city’s 45 major public parks and 12 of its 15 public pools were White-only. As pool desegregation began in the summer of 1963, a segregationist warned White families to keep their children out of the water, away from the “deadly threat” of “venereal infection” that allegedly ran rampant through the Black community. As historian Kevin Kruse writes, Whites with sufficient resources rushed to build backyard pools while working-class Whites sweated out the summer, seething that “their” public spaces had been stolen from them.

In contrast, the ban on interracial marriage merely “protected” parents from allowing their children to be traitors to the cause of White supremacy. If you were a racist and couldn’t prevent your daughter from marrying a Black man, except by dint of law, what kind of White parent were you anyway?

In many ways, then, the Loving story is tailor-made for individuals who support integration and justice in principle, but are loath to support virtually any public- or private-sector approach to make these tenets a reality. If some people look fondly on the story because it represents a “feel good,” essentially costless strike against blatant racism, Loving v. Virginia isn’t much of a victory.

Nonetheless, in practice as well as principle, the Lovings represent something important for genuine advocates of racial justice. In the five decades since the Loving decision, interracial marriage rates have soared. It’s folly to believe that Americans can marry and procreate their way to racial equality, but the rise of interracial marriage represents a much-needed cause for optimism in a time when unvarnished, unapologetic racism has made an ignoble comeback. In other areas of public life, such as schools, housing, and employment, laws striking down discrimination typically have been enforced weakly, if at all, by government, and undermined in the private sector. In contrast, the Lovings won. Period.