White Allyship Means a Transfer of Power

George Floyd. Rayshard Brooks. Elijah McClain. Breonna Taylor. Eric Garner. The list goes on. Public reaction to the regular murder of Black people by police has transitioned from devastation to mass outrage. Today’s racial justice movement has regalvanized the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement that began after the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of 17-year old Trayvon Martin. Solidarity actions have erupted internationally. The conspicuous shift in public opinion on issues of race, branded in 2019 as the “Great Awokening,” has reached an all-time high with protests in over 140 US cities after Floyd’s murder of May 25, 2020. But will the current resurgence in protests lead to enduring change?

With expectations for meaningful police reform exhausted due to successive failures, current demands are to defund police. This involves a significant reduction of public funds to end, for example, the provision of military weapons to municipal police departments. It also involves the diversion of public funds from police toward social services and communities in need. With substantial investment, long-neglected organizations run by and for Black people may decrease racialized inequalities in income, jobs, health, food security, housing, education, and other areas required to sustain collective well-being.

Source: Center for Talent Innovation, 2019. Being Black in Corporate America: An Intersectional Exploration. https://www.talentinnovation.org/publication.cfm?publication=1650

These demands are being heard. Minnesota’s governor called a special legislative session to curb police abuses as the city of Minneapolis considers defunding, an agenda shared by at least 16 cities in the U.S. New York lawmakers banned police chokeholds as did Los Angeles, where police misconduct cases are burgeoning. Other cities are limiting the powers of local police and criminalizing those who use lethal force. These include the protection of whistleblowers and the removal of protection from police involved in wrongful injuries. IBM will no longer sell facial recognition (FR) products, and the leading maker of police body cameras banned the use of FR in its products.

Outcomes of the racial justice movement have gone well beyond police defunding. Large corporations, political parties, universities, local governments, faith groups, media outlets, and other organizations have issued anti-racism statements. The National Football League now accepts players’ political protest. NASCAR banned the Confederate flag, and driver Bubba Wallace will compete in a car painted with Black Lives Matter. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are directing major funding to anti-racism organizations. At Facebook, the decision was stimulated by the loss of billions of dollars of advertising revenue from hundreds of advertisers, including multinationals like Coca-Cola, Pfizer, and Unilever.

Some school boards have eliminated the presence of police. White editorial staff at major newspapers have been reassigned. Monuments celebrating confederation leaders are falling. Confederate flags are being removed at the U.S. Marine Corps and the Navy. Statues of colonial leaders were toppled in the U.S., New Zealand, Belgium, and England. The archbishop of Canterbury declared that Jesus was not White. Merriam-Webster is expanding the definition of racism. The American Medical Association pronounced racism a public health issue in need of eradication, especially in policing. A group of about two dozen Democratic congress members kneeled in the Capitol’s Emancipation Hall in tribute to George Floyd. The momentum of reckoning is strong and palpable.

Public opinion is turning. Survey research firms like Civiqs and the Democracy Fund show a majority of Americans have unfavorable views of the police, recognize systemic racism, and support the racial justice movement. More people are concerned about police brutality against Blacks than they are about violent protests.

A salient feature of these actions is the mix of participants. Black, Brown and White, rich and poor, students and workers, urban and rural, conservatives and socialists are sharing messages of anti-racism. One study estimates between 53 and 61 percent of protestors in three cities are White. Cross-sectoral support, especially from those whose interests are perceived to be at risk in the matter, is an integral component of social change.

Having made inroads by social media influencers and seasoned activists, suddenly, it is ordinary White people who are critical of White privilege and power. Discourse has moved beyond White defensiveness and offers remarkably little compassion for Whites’ preoccupation with guilt, shame, or self-image. White support for Black Lives Matter and parallel organizations seems to have gone mainstream potentially signaling a new political status of anti-racism…or not.

While demonstrations continue on the streets, most activity occurs online. Articles, blogs, memes, and tweets encouraging White allyship circulate freely. Many observers regard actions concentrated online as having little impact. Whether described as performative allyship, optical allyship, or clicktivism, they function to appease White individuals’ conscience. While public declarations of anti-racism are better than silence, many sources make concrete recommendations for a more engaged participation, including advocating for grassroots organizations, lobbying political leaders, or donating funds. While undeniably valuable, these actions are individual in nature. They carry few if any risks for Whites and no responsibility for follow-up on a structural level.

This sparkling moment triggered by BLM and its diverse allies has led to critical changes. Until leadership, power, resources, and rewards are fairly distributed to those who are most affected by the inequitable impacts of economic and political decisions, there can be no sustained dismantlement of White supremacy. It is uncertain whether this could occur through voluntary benevolence or as a result of sweeping economic reform, as a concession to unending popular uprisings or through forcible removal in a revolution. However, until White political leaders, policymakers, business and community leaders withdraw their power and transfer it to racialized people, the gains made on the streets will be limited. To ensure concrete and permanent improvement to systemic inequalities, the racial justice movement must lead to a transformation in the exercise of power.

Notes: The data reflect judges appointed to Article III courts designated in the US Constitution as of July 2020. In gathering demographic data on the US population, the authors used information supplied by the US Census Bureau. The Bureau did not begin collecting comprehensive data on people who identify as ‘White, not Hispanic’ until the 1970s. The Census Bureau defined the category ‘Hispanic’ differently over time. In the 1940 census, the Bureau based an estimate of the US Hispanic population on the population who identified Spanish as their first language. The authors relied on data for ‘White, not Hispanic’ where figures were available but otherwise used the data for ‘White.’ Beginning with the 2000 census, individuals could report more than one race. ‘Non-White’ includes persons who identify as Black or African American, Asian, Hispanic or Latino, American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and people having two or more races. US Census Bureau data reflect 2020 estimates.

Sources: US Federal Judicial Centre, “Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789-present: Advanced Search Criteria,” available at https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/search/advanced-search (last accessed July 2020)

Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Population Division: Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States” (Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002), available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2002/demo/POP-twps0056.pdf

C SPAN, “U.S. Census Bureau, 1940 to 2010 Decennial Censuses” [PPT File], available at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/1940census/CSPAN_1940slides.pdf (last accessed July, 2020)

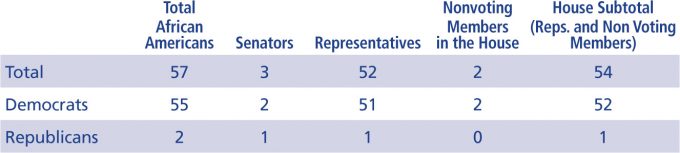

In 2020, 10.5 percent of the members of the U.S. Congress are Black, almost all of whom are Democratic house representatives (Number of African American Members in the 116th Congress). Pew Research Center found that the highest level of Black representation in a presidential Cabinet occurred during Bill Clinton’s first term when four out of fifteen Cabinet appointees were Black. When Barack Obama took office, he appointed only one Cabinet member who was Black—Attorney General Eric Holder. During Obama’s second term, there were four Black Cabinet appointees. The only Black Cabinet member to have been appointed by Donald Trump is Ben Carson, secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

According to the City Mayors Foundation, more than one-third of America’s top-100 cities are governed by African Americans. However, research at Rutgers University Center on the American Governor shows not a single Black governor among the three who are non-White. Among federal court judges, 80 percent were White as of August 2019; 13 percent of active federal judges are Black (Distribution of Judicial Appointment of Presidential Administrations, by Race and Ethnicity). Examining senior educational administration as another example of public sector leadership, the American Council on Education reveals that in 2016, 8 percent of all college presidents were Black.

In the private sector, the Center for Talent Innovation 2019 reports that 0.8 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs were Black (Representation of Black Adults in the U.S.). Black Enterprise Research shows that companies with diverse boards of directors financially perform well ahead of the national industry median compared to those companies without such boards. Despite this, only 40 percent of Black professionals believe that their employer’s D & I programs are effective in addressing their widespread barriers to advancement and microaggressions in the workplace. It frequently falls to Black professionals to explain workplace issues of racial inequity to colleagues who are often unprepared to accept the existence of inequity.

When reviewing the data, the problem of low BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) representation in positions of power becomes apparent. It reflects a lack of access to decision-making roles for racialized persons and compromised support for anti-racism initiatives. Disparities are not restricted to governance and justice; they are evident across organizations, sectors, and institutions.

Until there is a fundamental and radical change made to the level of representation of Blacks in leadership positions, the undeniably inequitable and racist effects on all racialized people will remain. Nothing less than radical change is necessary to transition from the dazzling revolutionary acts on the streets to a permanent and radical new investment into authentic power-sharing with BIPOC peoples.

Cynthia Levine-Rasky teaches in the Sociology Department at Queen’s University and Sabreena Ghaffar-Siddiqui teaches in the department of humanities and social sciences at Sheridan College. Levine-Rasky publishes on critical whiteness, Jewish identities, and antiracism. Ghaffar-Siddiqui focuses on the intersections of race, ethnicity, religion, and sociological social psychology. She publishes on immigrant and racialized identities, Islamophobia, racism, and antiracism.

Comments 1

Peter

January 10, 2021cool