Working Class Growing Pains

In a working-class neighborhood in Lowell, Massachusetts, I sat across the kitchen table from a 24-year-old white woman named Diana.

The daughter of a dry cleaner and a cashier, Diana graduated from high school and was accepted into a private university in Boston. She embarked on a criminal justice degree while working part-time at a local Dunkin’ Donuts, taking out loans to pay for her tuition and room and board. But after two years, Diana began to doubt whether the benefits of college would ever outweigh the costs, so she dropped out of school to be a full-time cashier.

She explained, “When I work, I get paid at the end of the week. But in college, I would have had to wait five years to get a degree, and once I got that, who knows if I would be working or find something I wanted to be.” Now, close to a hundred thousand dollars in debt, Diana has forged new dreams of getting married, buying a home with a pool in a wealthy suburb of Boston, and having five children, a cat, and a dog—by the time she is 30.

But Diana admitted that she can’t even find a man with a steady job to date, let alone marry, and that she will likely regret her decision to leave school: “Everyone says you can’t really go anywhere unless you have a degree. I don’t think I am going to make it anywhere past Dunkin’ when I am older, and that scares me to say. Like it’s not enough to support me now.”

Living with her mother and bringing home under $275 per week, Diana is stuck in an extended adolescence with no end in sight. Her yardsticks for adulthood—owning her own home, getting married, finishing her education, having children, and finding a job that pays her bills—remain spectacularly out of reach. “Your grandparents would get married out of high school, first go steady, then get married, like they had a house,” she reflected. “Since I was 16, I have asked my mother when I would be an adult, and she recently started saying I’m an adult now that I’m working and paying rent, but I don’t feel any different.”

What does it mean to “grow up” today? Even just a few decades ago, the transition to adulthood would probably not have caused Diana so much confusion, anxiety, or uncertainty. In 1960, the vast majority of women married before they turned 21 and had their first child before 23. By 30, most men and women had moved out of their parents’ homes, completed school, gotten married, and begun having children. As over a decade of scholarly and popular literature has revealed, however, in the latter half of the twentieth century traditional markers of adulthood have become increasingly delayed, disorderly, reversible—or have been entirely abandoned. Unlike their 1950s counterparts, who followed a well-worn path from school to work, and courtship to marriage to childbearing, men and women today are more likely to remain unmarried; to live at home and stay in school for longer periods of time; to switch from job to job; to have children out of wedlock; to divorce; or not have children at all.

Long And Winding Journey

Growing up, in essence, has shifted from a clear-cut, stable, and normative set of transitions to a long and winding journey. This shift has been greeted with alarm, and the Millennial Generation has often been cast as entitled, self-absorbed, and lazy. In 2013, for example, Time Magazine’s cover story on “The Me Me Me Generation” headlined: “Millennials are lazy, entitled narcissists who still live with their parents.” And a poll conducted in 2011 by the consulting firm Workplace Options found that the vast majority of Americans believe that Millennials don’t work as hard as the generations before them. The overriding conclusion is that things have gotten worse—and that young people are to blame.

But this longing to return to the past obscures the restrictions—and inequalities—that characterized traditional adult milestones for many young people in generations past. As the historian Stephanie Coontz reminds us, in the 1950s and ‘60s women couldn’t serve on juries or own property or take out lines of credit in their own names; alcoholism and physical and sexual abuse within families went ignored; factory workers, despite their rising wages and generous social benefits, reported feeling imprisoned by monotonous work and merciless supervision; and African Americans were denied access to voting, pensions, and healthcare.

The social movements for civil rights, feminism, and gay pride that emerged during subsequent decades erased many of these barriers, granting newfound freedoms to young adults in their wake. In many ways, young people today have a great deal more freedom and opportunity than their 1950s counterparts: women, especially, can pursue higher education, advance in professional careers, choose if and when to have children, and leave abusive marriages. And all young adults have more freedom to choose a partner regardless of sex or race.

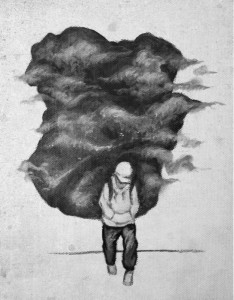

As psychologist Jeffrey Arnett argues: “More than ever before, coming of age in the twenty-first century means learning to stand alone as a self-sufficient person, capable of making choices and decisions independently from among a wide range of possibilities.” But that’s not the whole story. Just as many social freedoms for young people have expanded, economic security—stable, well-paid jobs, access to health insurance and pensions, and affordable education—has contracted for the working class. Meanwhile, the growing fragility of American families and communities over the same time period has placed the responsibility for launching young adults into the future solely on the shoulders of themselves and their parents.

For the more affluent young adults of this “Peter Pan Generation”—those with a college fund, a parent-subsidized, unpaid internship, or an SAT coach, the freedom to delay marriage and childbearing, experiment with flexible career paths, and pursue higher education grants them the luxury to define adulthood in their own terms. But working-class men and women like Diana have to figure out what it means to be a worthy adult in a world of disappearing jobs, soaring education costs, shrinking social support networks, and fragile families.

From 2008-2010, I interviewed 100 working-class men and women between the ages of 24 and 34—people who have long ago reached the legal age of adulthood but still do not feel “grown up.” I went from gas stations to fast food chains, community colleges to temp agencies, tracking down working-class young people, African Americans and whites, men and women, and documenting the myriad obstacles that stand in their way. And what I heard was profoundly alarming: caught in the throes of a merciless job market and lacking the social support, skills, and knowledge necessary for success, working-class young adults are relinquishing the hope for traditional markers of adulthood—a home, a job, a family—at the heart of the American Dream.

My conversations with these men and women uncovered the contours of a new definition of working-class adulthood: one characterized by low expectations of loyalty in work, wariness toward romantic commitment, widespread distrust of social institutions, and profound isolation from and hostility towards others who can’t make it on their own. Simply put, growing up today means learning to depend on no one but yourself.

Work And Love Amid Inequality

Pervasive economic insecurity, fear of commitment, and confusion within institutions make the achievement of traditional markers of adulthood impossible and sometimes undesirable. The majority of the young people I spoke with bounce from one unstable service job to the next, racking up credit card debt to make ends meet and fearing the day when economic shocks—an illness, a school loan coming out of deferment—will erode what little stability they have.

Upon leaving high school, they quickly learned that they shouldn’t expect loyalty or respect from their jobs. Jillian, a 26-year-old white woman, started out as a line cook, making $5.50 an hour the year she graduated from high school. Under the guidance of her manager, she worked her way up the line until she was his “right hand man,” running the line by herself and making sure everyone cleaned up their stations at the end of a long day. When Bill died suddenly from a heart attack, the owner waited to hire a new manager, causing a year of skeleton crews, chaos, and back-breaking 70-hour work weeks.

Jillian knew that she was lucky to have all those hours a week to work, especially in the recession, and she didn’t complain: “…you basically worshipped the ground they walked on because they gave you a job. You had to keep your mouth shut.” But when Jillian pushed for changes and the owner snapped, “You won’t get respect anywhere else, so why expect it here?” She quit. “I thought I had it going good for a while there. But everything really came to a screeching halt, and I bought a car, and now not having a job…I feel like I’m starting over.”

Indeed, growing up means learning that trusting others, whether at school, home, or work, will only hurt them in the end. Rob is a 26-year-old white man whom I met while recruiting at a National Guard training weekend in Massachusetts. Rob told me his story in an empty office at the armory because he was currently “crashing” on his cousin’s couch. When he graduated from his vocational high school, he planned to use his training in metals to build a career as a machinist: “Manufacturing technology, working with metal, I loved that stuff,” he recalled longingly. As he attempted to enter the labor market, however, he quickly learned that his newly forged skills were obsolete.

“I was the last class at my school to learn to manufacture

tools by hand,” he explained. “Now they use CNC [computer numerical controlled] machine programs, so they just draw the part in the computer and plug it into the machine, and the machine cuts it… I haven’t learned to do that, because I was the last class before they implemented that in the program at school, and now if you want to get a job as a machinist without CNC, they want five years’ experience. My skills are useless.”

Over the last five years, Rob has stacked lumber, installed hardwood floors, landscaped, and poured steel at a motorcycle factory. His only steady source of income since high school graduation has been his National Guard pay, and although he recently returned from his second 18-month deployment in Afghanistan, he is already considering a third: “I am looking for a new place. I don’t have a job. My car is broken. It’s like, what exactly can you do when your car is broken and you have no job, no real source of income, and you are making four or five hundred dollars a month in [military] drills.” He explains his economic predicament: “Where are you going to live, get your car fixed, on $500 a month? I can’t save making 500 bucks a month. That just covers my bills. I have no savings to put down first and last on an apartment, no car to get a job. I find myself being like, oh what the hell? Can’t it just be over? Can’t I just go to Iraq right now? Send me two weeks ago so I got a paycheck already!”

Insecurity seeps into the institution of family, leaving respondents uncertain about both the feasibility and desirability of commitment. Deeply forged cultural connections between economic viability, manhood, and marriage prove devastating, as men’s falling wages and rising job instability leave them uncertain about the meanings of masculinity in the twenty-first century. Brandon, a 34-year-old black man who manages the night shift at a women’s clothing chain, explained matter-of-factly, “No woman wants to sit on the couch all the time and watch TV and eat at Burger King. I can only take care of myself now. I am missing out on life but making do with what I have.”

For working-class women who have grown up shouldering immense social and economic burdens on their own, being responsible for another person who may ultimately let them down doesn’t feel worth the risk. Lauren, a 24-year-old barista who was kicked out of her father’s house when she came out as a lesbian, has weathered years of addiction, homelessness, and depression, finally emerging as a survivor, sober and able to pay her own rent. She has chosen to remain single because she fears having to take care of someone else.

“I mean, everybody’s life sucks, get over it! My mom’s an alcoholic, my dad kicked me out of the house. It’s not a handicap; it has made me stronger. And I want someone who has you know similarly overcome their respective obstacle and learned and grown from them, rather than someone who is bogged down by it and is always the victim.” As Lauren suggests, since intimacy carries with it the threat of self-destruction, young working-class men and women forego the benefits of lasting commitment, including pooled material resources, mutual support, and love itself.

Children symbolize the one remaining source of trust, love, and commitment; while pregnancies are usually accidental, becoming a parent provides motivation, dignity, and self-worth. As Sherrie, whose pregnancy gave her the courage to break up with her abusive boyfriend, explained: “You have a baby to take care of! My daughter is the reason why I am the way I am today. If I didn’t have her, I think I might be a crack-head or an alcoholic or in an abusive relationship!” Yet the social institutions in which young adults create families can work against their desire to nurture and protect their children.

Rachel, a young black single mother, joined the National Guard in order to go to college for free through the GI Bill. However, working 40 hours a week at her customer service job, attending weekend army drills, and parenting has left her with little time for taking college classes. Hearing rumors that her National Guard unit may deploy to Iraq for a third time in January, she is tempted to put in for discharge so that she is not separated from her son again. However, her desire to give her son everything she possibly can—including the things she can buy with the higher, tax-free combat pay she receives when she deploys—keeps her from signing the papers: “I am kinda half and half with the deployment coming up. I could use it for the money. I could do more for my son. But I missed the first two years of my son’s life and now I might have to leave again. It’s just rough. You can’t win.”

Distrust And Isolation

Common celebrations of adulthood—whether weddings, graduations, house-warming’s, birthdays—are more than just parties; they are rituals for marking community membership and shared, public expressions of commitment, obligation, rights, and belonging. But for the young men and women I spoke with, there was little sense of shared joy or belonging in their accounts of coming of age. Instead, I heard story after story of isolation and distrust experienced within a vast array of social institutions, including higher education, the criminal justice system, the government, and the military. While we may think of the life course as a process of social integration, marked by public celebrations of transitions, young working-class men and women depend on others at their peril.

They believe that a college education will provide the tools for success. Jay, a 28-year-old black man, struggled through seven years of college. He failed several classes after his mother suffered a severe mental breakdown. After being expelled from college and working for a year, helping his mom get back on her feet, he went before the college administration and petitioned to be reinstated. He described them as “a panel of five people who were not nice.” As Jay saw it, “It’s their job to hear all these sob stories, you know I understand that, but they just had this attitude, like you know what I mean, ‘oh your mom had a breakdown and you couldn’t turn to anyone?’ I just wanted to be like, fuck you, but I wanted to go to college, so I didn’t say fuck you.” When he eventually graduated, when he was 25, he “was so disillusioned by the end of it, my attitude toward college was like, I just want to get out and get it over with, you know what I mean, and just like, put it behind me, really.” He shrugged: “I felt like it wasn’t anything to celebrate. I mean I graduated with a degree. Which ultimately I’m not even sure if that was what I wanted, but there was a point where I was like I have to pick some bullshit I can fly through and just get through. I didn’t find it at all worthwhile.”

Since graduating three years ago, with a communications major, Jay has worked in a series of food service and coffee shop jobs. Reflecting on where his life has taken him, he fumed: “They were just blowing smoke up my ass—the world is at my fingertips, you can rule the world, be whatever you want, all this stuff. When I was 15, 16, I would not have envisioned the life I am living now. Whatever I imagined, I figured I would wear a suit every day, that I would own things. I don’t own anything. I don’t own a car. If I had a car, I wouldn’t be able to afford my daily life. I’m coasting and cruising and not sure about what I should be doing.”

Christopher, a 24-year-old, who has been unemployed for nine months, further illustrates how distrust and isolation is intensified by bewildering interactions with institutions. As he put it, “I have this problem of being tricked…Like I will get a phone call that says, you won a free supply of magazines. And they will start coming to my house. Then all of a sudden I am getting calls from bill collectors for the subscriptions to Maxim and ESPN. It’s a run around: I can’t figure out who to call. Now I don’t even pick up the phone, like I almost didn’t pick up when you called me.”

Recently, Christopher was taxed $400 for not purchasing mandatory health insurance in Massachusetts, which he could not afford because he was unemployed, and did not know how to access for free. Like many of my respondents, he lacks the skills and know-how to navigate the institutions that frame the transition to adulthood. He tells his coming of age story as one incident of deception after another—each of which incurs a heavy emotional and financial cost. But while he acknowledges that he has not achieved the traditional markers of adulthood, he still believes that he is at least partially an adult because of the way he has learned to manage his feelings of betrayal: “I ended up the way I am because of my experiences. I have seen crazy shit. Like now if I see someone beating someone up in the street, I don’t scream. I don’t care. I have no emotions or feelings.” Growing up hardened against and detached from the world, and dependent on no one, Christopher protects himself from the possibility of trickery and betrayal.

Remaking Working-Class Adulthood

The working-class men and women I spoke with lack the necessary knowledge, skills, credentials, and money to launch themselves into a secure adult future, as well as the social support and guidance to protect themselves from economic and social turmoil. But despite their profound anger, betrayal, and loss, they do not want pity—and they do not expect a handout. On the contrary, at a time when individual solutions to collective structural problems is a requirement for survival, they believe that adulthood means taking responsibility for one’s own successes and failures. Emma, who works as a waitress, praised her grandfather who worked his way up digging ditches for a gas company; she says it is now up to her to “take what you are given and utilize it correctly.” Similarly, Kelly, a line cook who has lived on and off in her car, explains, “Life doesn’t owe me any favors. I can have a sense of my own specialness and individuality, but that doesn’t mean that anybody else has to recognize that or help me accomplish my goals.”

This bootstrap mentality, while highly praised in our culture, has a darker side: blaming those who can’t make it on their own. Wanda, the daughter of a tow-truck driver who wants to go to college but can’t afford the tuition, expresses anger at her parents’ lack of economic support: “I feel like it’s their fault they don’t have nothing.” Working-class youth have little trust even in those closest to them and—despite the social and economic forces that work against their efforts—they blame themselves for their shortcomings.

Julian, a young black man, is a disabled vet who is unemployed, divorced, and living with his mother. Describing his inability to find a steady job and lasting relationship, he tells me: “…Every day I look in the mirror, and I could bullshit you right now and tell you that race has something to do with it. But at the end of the day looking in the mirror, I know where all my shortcomings come from. From the things that I either did not do or I did and I just happen to fail at them.” They believe that understanding their shortcomings in terms of structural barriers to mobility is a crutch; both blacks and whites are hostile toward others who do not take sole responsibility for their own failures.

John, a 27-year-old black man who sells shoes, explained: “Society lets it [race] affect me. It’s not what I want to do, but society puts tags on everybody. You gotta be presentable, take care of yourself. It’s about how a man looks at himself and how people look at him. Some people use it as a crutch, but it’s not gonna be my crutch.” That is, while black men and women acknowledge that discrimination persists, they see navigating racism as an individual game of cunning. All make a virtue out of not asking for help, out of rejecting dependence and surviving completely on their own, mapping these traits onto their definitions of adulthood. Those who fail to “fix themselves” are met with disdain and disgust—they are not worthy adults.

This hardening against oneself and others could have profound personal and political consequences for the future of the American working class. Its youngest members embrace self-sufficiency, blame those who are unsuccessful in the labor market, and choose distrust and isolation as the only way to survive. Rather than target the vast social, economic, and cultural changes that have disrupted the transition to adulthood—the decline of good jobs, the weakening of unions, the shrinking of communities—they target themselves. In the end, if they have to go it alone, then everyone else should, too. And it is hard to find even a glimmer of hope for their futures.

Their coming of age stories are still unfolding, their futures not yet written. In order to tell a different kind of story—one that promises hope, dignity, and connection—they must begin their journeys to adulthood with a living wage and the skills and knowledge to confront the future. They need neighborhoods and communities that share responsibility for launching them into the future. And they need new definitions of dignity that do not make a virtue out of isolation, self-reliance, and distrust. The health and vibrancy of all our communities depend on the creation and nurturance of definitions of adulthood that foster connection and interdependence.

Recommended Resources

Cherlin, Andrew. The Marriage Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today (Vintage Books, 2009). Traces the transformation of American families over the past century and points to alarming class-based differences in marriage patterns.

Edin, Kathryn, and Timothy J. Nelson. Doing the Best I Can: Fatherhood in the Inner City (University of California Press, 2013). Sheds light on the experiences of low-income fathers and their struggles to care for their children despite their lack of jobs and rocky relationships with their children’s mothers.

Furstenberg, Frank F., Sheela Kennedy, Vonnie C. McLoyd, Rubén G. Rumbaut, and Richard A. Settersten Jr. “Growing Up Is Harder to Do,” Contexts (2004), 3: 33–41. Provides a comprehensive overview of the delayed transition to adulthood for working-class youth.

Hacker, Jacob. “The Privatization of Risk and the Growing and Economic Insecurity of Americans” (2006). Documents the recent cultural and political shifts in the United States that have demolished social safety nets and promoted self-reliance, untrammeled individualism, and personal responsibility.

Kalleberg, Arne L. “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers,” American Sociological Review (2009), 74: 1-22. Explains how and why working-class jobs have become increasingly scarce, insecure, and competitive.