Posters for the Netflix series "13 Reasons Why"

“13 Reasons Why” and the Pressing Need for a Sociology of Suicide

Note: this article contains spoilers and detailed discussions of suicide and sexual assault.

Recently, Netflix released a series based on the young adult novel 13 Reasons Why. It’s about an adolescent girl named Hannah who completes suicide, and each episode is narrated by Hannah— by way of seven cassette tapes she left behind to tell her story. Each cassette features two reasons why she chose suicide, and each reason centers on one of her high school peers. As such, the show revolves around a group of suburban teens and adults grieving Hannah’s death and trying to make sense of this unusual suicide “note.” The show is graphic, particularly in the depiction of Hannah’s suicide, and intense. It also provides a unique window into teen culture in a relatively affluent community. For these reasons, it presents sociologists with an important and timely platform to contribute to the national conversation about a classic sociological phenomenon of interest: suicide. First, the good.

What 13 Reasons Gets Right

What 13 Reasons Gets Right

One of the most prominent features of the television show is its relatively accurate depiction of adolescent life in middle-class and affluent communities, and, especially, the toll high school peer cultures can exact. Against this backdrop, the show skillfully deals with some serious social problems.

First, it takes teen pain seriously. Unlike many shows, it does not shy away from showing teens’ problems as they experience them: as serious, complex situations without easy solutions.

Second, as some critics have pointed out, 13 Reasons provides a compelling examination of rape culture, misogyny, and sexual harassment in high school (suicidologists often neglect this important context, as fleshed out in USA Today). Hannah and other girls are repeatedly harassed, objectified, and, in some cases, assaulted. These depictions are extremely emotional and some are graphic; the audience experiences these assaults from the victim’s perspective. The show does not ignore—or allow us to ignore—how rape culture hurts youth. Further, it provides important role modeling of unacceptable and acceptable behaviors around sex. It clearly illustrates what consent is (and what it is not), and it depicts how one might ask for sexual consent without “killing the mood” (something youth often are concerned about). It even presents the proper reaction to a woman rescinding consent: in one scene, Hannah eagerly consents to hooking up with Clay, but she gets overwhelmed and changes her mind. Clay stops immediately and responds to Hannah’s apparent distress in a caring manner. These lessons are both very important and very hard to convey well.

Third, though it is not explicit, the show underscores the social roots of suicide. Despite Durkheim’s seminal study over a century ago, social scientists and lay people still tend to conceptualize suicide as caused by mental illness absent the social factors that can contribute to mental health problems. From bullying to sexual harassment and social isolation, we see, with startling clarity, how the social world affects Hannah’s developing mental health problems and eventual suicide.

Finally, and most importantly, 13 Reasons has opened up a space for much-needed conversations about teen suicide and sexual assault.

And Where 13 Reasons Goes Wrong

Despite the show’s strengths, mental health organizations have been alarmed by its popularity. They have good reason: there is substantial evidence that exposure to the suicide of a role model (even if that role model is a fictive character) can amplify individuals’ vulnerability to suicide. This effect goes by many names—suicide “contagion,” “diffusion,” “suggestion,” or “imitation” —and parents and schools are rightfully worried about it. Many have trouble directly addressing suicide with youth because they fear that talking openly and honestly about suicide can cause suicide. However, research shows that while role modeling suicide as an option can be harmful, talking about suicide is NOT. In fact, there is some evidence that talking to youth about suicide can actually diminish suicidality. (For a review, check out Thomas Joiner’s Myths about Suicide.)

So, what’s the difference? This is where our research comes in. For many years, suicide “contagion” has been poorly understood. Some psychologists argue that that the phenomenon is a straw man, concealing preexisting vulnerabilities to suicide (we would argue that the best statistical evidence suggests this is not the case). Others argue that suicide is “contagious” because, by discussing it, youth learn about a specific method to die by suicide. That, too, feels insufficient: in this age of information, just about anything is readily accessible on the Internet. What we have found, and what others suggest (particularly Thomas Niederkrontenthaler and his coauthors), is that the stories we tell about suicide matter in whether suicide seems like a salient option—particularly if youth can identify with the perceived motive of a person who died by suicide. Because 13 Reasons has so resonated with young audiences, it’s not unreasonable to worry that Hannah’s choice to end her life under a certain set of circumstances may make that path more accessible to youth who face similar challenges.

Additionally, the story gets a lot wrong about suicide, and that could promote inaccurate ideas about the circumstances of Hannah’s suicide, who is vulnerable to suicide, and how to tell if someone needs help.

The first mistake the story makes is that it underplays Hannah’s psychological pain. A great deal of emotional and psychological pain precedes suicide, but, Hannah’s calm voice in the early episodes makes her suicide seem less about psychological pain from social and physical abuse and more about her exacting some sort of revenge on those who tormented her. Promoting suicide as a means to vengeance is not a good idea.

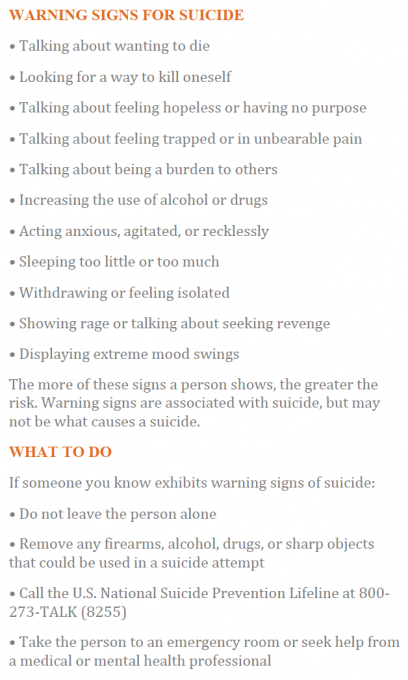

The second mistake is that Hannah tells the audience that youth on the verge of suicide look like any other youth. This is usually not accurate. Again, the psychological pain that precedes suicide is nearly always substantial enough that it shapes a person’s observable behavior. Though bereaved people sometimes say that a person’s suicide was completely unexpected (as Hannah asserts), in our research, we find that the warning signs were often present and friends and family were often deeply concerned about the person, even if they also note that they are shocked by the death. Very few actually asked, “Are you contemplating suicide?”—the possible answer (understandably) terrified them.

But there are trainings available that teach the warning signs for suicide and what to do if you are concerned about someone. There are 24/7 crisis lifelines to call or text. And there is accessible literature (see pages 24-25 of this manual) that teaches how to speak to youth about suicide and suicide loss. At a minimum, we must teach caring people to overcome their anxieties about asking directly about suicide. It will not push someone toward suicide; instead, it may save their life.

Third, if contagion is problematic and Hannah’s character presents an understandable narrative of teen life, the realistic depiction of Hannah’s suicide truly could be dangerous. Producers defend the scene by arguing that the gory details of Hannah’s death should de-glorify suicide for teens. Yet, they are failing to recognize that glorification—from a sociological perspective—is much more than deification or celebrity; it is propagating cultural meanings that many adolescents can easily identify with and making them available, accessible, and applicable to their own existence.

Finally, the viewer is never invited to contemplate how Hannah’s choice to explicitly blame her peers for her suicide was incredibly and inevitably cruel. This is particularly obvious in the case of Clay, who she explicitly notes is not to blame, but who she traumatizes by including him as one of the reasons why she chose suicide. Survivors of suicides—parents, friends, siblings—deal with a lot of guilt and shame as they try to make sense of a senseless situation. Perhaps toward the end of the show, the producers could have reduced some of its harmful role modeling of suicide by emphasizing Hannah’s cruelty, exacted through the tapes that form the show’s backbone. Likewise, when her parents are finally made aware of the tapes, we could see them talking to the kids about how Hannah’s death is not their burden to carry. Instead, failing to end the show with some semblance of a positive narrative simply reinforced the chasm between adolescent and adult culture and further validated Hannah’s actions. This was a terrible missed opportunity for the show.

What’s Next

Ultimately it is hard to predict how 13 Reasons Why—the novel or the show—might shape the mental health of youth. Our society is marked by unequal access to mental healthcare, the stigmatization of mental health problems, and the oppression of sexual assault victims, and we often fail to intervene meaningfully in adolescent suffering. We offer youth platitudes, like “It gets better,” minimizing their present suffering in service of an unknowable future. In other words, we expect kids to just accept that high school culture sucks. Perhaps this show will bring some shifts. Indeed, because so many youth are watching it and reacting, the only real question is how parents, schools, and communities will respond to a “moment” in which we might talk meaningfully about adolescent suffering, suicide, and sexual assault? Will we take dive into the tough conversations? Will we pay more attention to adolescent mental health in schools? Will we provide youth—all youth—with access to the care they may desperately need?

THE NATIONAL SUICIDE PREVENTION LIFELINE 800-273-TALK(8255)

A free, 24/7 service that can provide suicidal persons or those around them with support, information, and local resources.

Anna S. Mueller is in the department of comparative human development at the University of Chicago. She studies suicide, adolescent development, and education. Seth Abrutyn is in the department of sociology at the University of British Columbia. He studies suicide, emotions, and general theory. Together with Melissa Osborne, they are the authors of “Durkheim’s Suicide in the Zombie Apocalypse,” Contexts Spring 2017.

Comments 13

Martin Buuri Kaburia

June 29, 2017How sad,more should be done

DeQuincy Lezine

July 1, 2017This post is a well-written and even-handed analysis of the 13 Reasons Why show that approaches the topic in a balanced way. Excellent work. I agree that the suicide prevention community has largely ignored the subjects of sexual harassment and sexual violence that are rampant throughout the series, and they are important issues in our society. Multiple chapters in my resource book for parents that responds to 13 Reasons Why tackle those concerns (https://www.amazon.com/dp/B072134NPG). Your point about having suicide placed squarely within a social context and not considered as only attached to a mental disorder is also well taken. While Hannah may have had some mental health challenges, people should understand her suicidal pain as a human struggle within a social context.

tea tv app

August 18, 2017Yeah more should be done

rock.lviv.ua

August 2, 2018Brand loyalty, client satisfaction, brand awareness,

referrals and purchases are achievable through marketing with email, however it is necessary for marketers to understand their objectives and priorities at the beginning of the campaign. Customers

will not send feedback unless you produce a request in the each person that have

purchased in you. The digital marketing agency formulates a technique that

has many on-page and off page techniques for

the same.

Sam Black

August 29, 2019Recently, Netflix released a series based on the young adult novel 13 Reasons Why. For us students it is very useful and it can be of more benefit to each of you. I was helped to research this through click reference which helps me a lot. So go ahead and you can get the same.

Kate

November 14, 2019Thank you for the article, this issue really matters, especially for teenagers who are among the risk group. I saw the illustration of this in the well-known musical Dear Evan Hansen https://dearevanhansenshow.com/ where the main character has those issues of being fully socially involved.

Glenna G. Woods

December 15, 2019Hello, Kate, you provided nice information, I really like your post or information as well.

Carl

January 30, 2020Thanks

RobertJFlores

July 21, 2020Hey guys, I am really happy with this post as here anyone can discuss their problems. I am also suffering from an assignment writing problem. I have to write five assignments in a week. Then my I found https://edubirdie.org/ which is an interesting writing service. Here I got the best professional writers which are very supportive. Here I got fully assured material that is plagiarism free. One best thing is that on this site I got quick response. You must try this site.

Athan1953

July 21, 2020Hey guys, I am really happy with this post as here anyone can discuss their problems. I am also suffering from an assignment writing problem. I have to write five assignments in a week. Then my I found https://edubirdie.org/ which is an interesting writing service. Here I got the best professional writers which are very supportive. Here I got fully assured material that is plagiarism free. One best thing is that on this site I got quick response. You must try this site.

AmandaBrooks

September 3, 2020Looking for pay for essays ? You will find them on our website! Just click here.

Gustavo Woltmann

September 29, 2020I don't say anything about this because its the wrong thing. I think, most suicide cases of depression because it's very bad causes. I pray to god then please stop this type of situation. I am a brazil musician Gustavo Woltmann

Edgar Toliver

April 27, 2021very cool