A public library's Banned Books Week display prominently features Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. Photo by Charles Hackley, Flickr CC. https://flic.kr/p/MuL5VM

Book Bans Impact Students’ Worldviews

Do you remember the first book you read that changed your life?

I do.

It was Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. I was in an African-American Literature class in college, and the professor assigned an excerpt from the book during the semester. And while I no longer remember much of the excerpt, I still remember how Ellison’s words made me feel. One line still echoes in my memory: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

While Ellison, as a Black man, was writing from a lived experience that was not my own, his understanding of invisibility resonated with me as I struggled to make sense of what it meant to be both seen and unseen as a queer, mixed-race, White-presenting woman who grew up poor. Ellison’s book, along with many others, made a critical imprint on what I thought and understood about the world with regards to power and domination. It changed how I saw the structures of race, gender, class, and sexual orientation—and what I thought and understood about myself.As both a sociologist and lifelong book lover, I’ve started to think a lot about the recent surge in book bans in schools across the United States and how they maintain White nationalist, capitalist, and heteronormative patriarchal ideological control over students by alienating them from a multitude of stories, narratives, histories, and ideas that might shift, challenge, and/or disrupt oppressive beliefs and attitudes. Banned books can inform students’ beliefs on how gender and sexuality work (or doesn’t); whether (and how) White supremacy and anti-Black racism impacts people’s lives, identities, and material realities; or even help students establish baseline knowledge about lives different from their own. Black, Brown, and/or queer authors write themselves and others like them into existence through their books—and students not only see themselves in these books, they begin to understand and believe that another (and less oppressive) world is possible.

To better understand the ideological impact of book bans, it’s critical to know where they’re happening, how often they’re occurring, and which books are being targeted. Non-profit organizations like Pen America have been instrumental in recording this kind of information and making it accessible to the broader public. From 2021-2022, Pen America maintained an “Index of School Book Bans” database to track banned books across the United States; it recorded “2,532 instances of individual books being banned affecting 1,648 unique book titles by 1,261 different authors.” The database recorded the titles and authors of the books, the number of times a specific book was banned or challenged, which state and school district the books were being banned in, and details about whether the ban came from an administrator or represented a formal state challenge. Users of the database can even see whether a particular book was banned in a classroom or in a school library.

Book bans, it turns out, aren’t popping up in every state with the same intensity. Many of the book bans are concentrated in more politically conservative states in the South and the Midwest. States with the most bans include Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania. Texas and Florida have the most book bans—between 751-1,000 and 501-750, respectively. Comparatively, more left-leaning states like New York and Washington have between 1-10 bans. Quite a few states—including California, Arizona, and Nevada—have no bans at all.

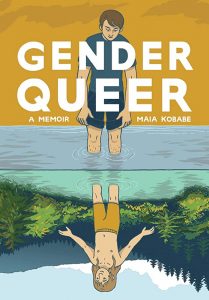

The books targeted by bans often express ideas that challenge or disrupt dominant and often oppressive framings of the world. Some banned books express transgressive ideas about binary gender identity and compulsory heteronormativity. In fact, Pen America reports that 41% of the bans target books with LGBTQIA+ content and 22% grapple with sexual content. During the 2021-2022 school year, the number one banned book was Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer: A Memoir. Banned in school libraries and classrooms on 41 occasions, Kobabe’s coming-of-age graphic memoir explores gender and sexuality through the lens of a young non-binary and asexual person. What happens to the student who reads Kobabe and has their understanding of gender and sexuality stretched beyond the binary? (And why, we must wonder, is that outcome so threatening?)Other targeted books wrestle with the intersections of queerantagonism and anti-Blackness in the United States. Pen America reports that 40% of targeted books feature primary characters of color and 20% of targeted books deal with race and racism. For example, George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue shares the experiences of a young, queer, Black boy navigating life, family, love, pain, and, later, an HIV diagnosis. Johnson’s book has been challenged with bans or proposed bans in schools 29 times in states like Tennessee, Missori, Kansas, Washington, Utah, Texas, Pennsylvania, and New York on the grounds of “descriptions of sex between the author and other people in two chapters.” Reading Johnson’s work, students can begin to humanize queer Black folks, normalize Black and queer love, and detach pathology from queer and Black bodies.

While book bans can erase Black and Brown and queer stories, narratives, and authors from schools, what’s at stake here goes beyond bookish diversity, inclusion, and representation in classrooms and libraries. It’s about the erasure of possible futures and radically new, and freer, ways of thinking about the social world and the oppressive systems that define it. It’s about the erasure of histories, stories, and lived experiences that exist both within and yet in bold defiance of white heteronormative ideological dominance. These books can offer students radical new or alternative ways of thinking about the world they’re born into, co-create, and ultimately (re)produce.But there’s still hope in resistance. Students can borrow “banned books” from their local libraries, for instance, though libraries are sometimes geographically inaccessible or have limited access to newer books. (What’s more, some fear that with the rise of book bans, libraries could vanish altogether.) Other folks are fighting back by weaponizing the book bans themselves. For example, a parent in Utah in the Davis School District is calling for a ban of the Bible on the grounds that, under the state’s book banning law, it is pornographic. And more recently, there’s been a larger political pushback to the bans; Florida Democrats have called for a ban of Governor Ron DeSantis’s book in Florida schools since it includes the topics of violence and gender identity.

Alyssa Lyons is the Sociology Department at Lehman College CUNY. She studies critical education.

Comments 2

kaylestoinis

May 2, 2023The books targeted by bans often express ideas that challenge or disrupt dominant and often oppressive framings of the world.

Peter Campbell

August 22, 2023"Book Bans Impact Students' Worldviews" is a thought-provoking exploration of the consequences of restricting access to literature. This blog highlights the critical role books play in shaping young minds and fostering a well-rounded perspective on the world.

As someone who values the power of storytelling, I can't help but wonder about the untold stories that could continue to influence students if given the chance. If you're a writer or an educator seeking to preserve the diversity of voices and ideas, let me introduce you to Writers of the West—the home of the most exceptional fictional book writers in town.

Our team is dedicated to helping authors and educators craft compelling narratives that inspire critical thinking and empathy. Whether you're working on a novel that challenges the status quo or educational materials that broaden horizons, our ghostwriters have the expertise to bring your vision to life.

Don't let the silence of banned books drown out the voices that need to be heard. Reach out to us today, and together, we can ensure that important stories continue to shape the minds of future generations.

📖🖋️ #WritersOfTheWest #Ghostwriting #BannedBooks #LiteratureMatters #Storytelling