iStockPhoto.com // Anton Vierietin

Lack of diversity on college campuses fuels naïve belief in meritocracy

Runaway income segregation and inequality call attention to the changing conditions of life on each side of the growing economic divide. But as social worlds diverge along socioeconomic fault lines, it is important to ask: How do we learn about the lives of others?

A recent study of mine tackles this question directly, as I set out to learn how American college students, growing up in a country defined by inequality and segregation, learn about their society. I traced beliefs about inequality across ten cohorts of U.S. college students between 1998 and 2010 (totaling 141,597 students across 436 institutions). What I found is that the college context deeply shapes how students come to understand inequality.

Historically, colleges have held dear a mission to educate tomorrow’s leaders about their country’s past and present, the democratic processes and institutions that govern, and their part in it all. At the same time, they have the potential to broaden perspectives and increase intergroup understanding and empathy. Currently, however, the majority of students receive only limited exposure to people from different racial and class backgrounds on the university campus.

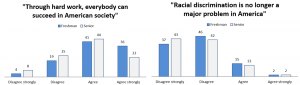

As the Supreme Court brings an end to race-conscious admissions—known more widely as affirmative action—we must consider the consequences for not just who gets into universities, but also the civic role and equalizing promise of college. Through recruitment and admission practices, colleges determine the exclusivity and diversity of the place where students learn important lessons about social and racial inequality in the United States. In doing so, they shape the development of students’ beliefs about inequality. These can range from a meritocratic view of success driven by hard work alone to a more structural understanding of stratified system shaped by racial and socioeconomic hierarchies.To study students’ changing beliefs about inequality, I combined a survey taken before students started college, typically at freshman orientation, with an exit survey taken by those same students in the spring semester of senior year. This allowed me to measure whether and why students changed their beliefs. I paid particular attention to how students’ shared living arrangements with a roommate—an intimate and up-close lens into the social and material conditions of another person’s life—may have conditioned their experience.

So, do students believe that America is a meritocracy and that racial discrimination is a thing of the past? I find that, upon entry to college, most freshmen believe in meritocracy while also recognizing racial inequalities. But by senior year about only half of students hold on to those beliefs, with 20% growing more convinced that theirs is a meritocratic society and 30% coming to see their society as structurally unequal.

Crucially, those students who grew more convinced that theirs is a meritocratic society typically had a college experience marked by an absence of exposure to racial or economic diversity.

Conversely, my research reveals that having a roommate from a different racial or ethnic group is associated with students developing a less meritocratic understanding of America. Black and Hispanic students in particular lose faith in the American Dream, and Asian students come to see more racial discrimination.

Ironically, White students are less affected by their roommate than non-White students. This asymmetry may be illustrative of some people’s higher attentiveness to personal disadvantages than others. It’s important acknowledge, as well, that what may constitute an eye-opening experience for one student can be a draining and psychologically costly confrontation for another.

My findings also show that the effect of having a roommate from a different race or ethnicity is strongest in places that lack socioeconomic and racial diversity, such as colleges with a majority White student body or schools where the lion’s share of students have college-educated parents. That is, diversity experiences matter most where they are least likely to happen.

Despite the potential for broadening perspectives, then, colleges tend to reinforce inequality in two key ways. First, credentials increase the economic gap between graduates and the 70% of Americans without a degree. And second, when colleges lack diversity, tomorrow’s educational elite learn to legitimize the growing gap as meritocratically deserved.In a country marked by deep racial and economic divides, adolescents who grow up encapsulated in privilege develop a naïve understanding of American meritocracy. For these students, the college experience undermines rather than serves the civic and integrative role of higher education.

More exposure to people of different walks of life creates conditions for students to develop an awareness of structural processes that shape inequality. Be it through purposeful roommate pairing, inclusive admission policies, or affirmative recruitment efforts, a college environment that better reflects our diverse population would impact the perspective of 20+ million students currently in college—and with it, public opinion and U.S. politics.

Jonathan Mijs is in the Department of Sociology at Boston University. He studies how people perceive, explain, and feel about racial and economic inequalities.

Comments 2

Dianne

October 1, 2023nice

things to do

January 8, 2024Thank you so much! I learned a lot from the insight you shared.