Ironically, graffiti memorializes slain police officers in NYC. Photo by A. Golden via Flickr CC

The Shame Game: New York City Cops’ Union and Power Politics

Wenjian Liu’s funeral marked the fourth time the New York Policemen’s Benevolent Association—the cops’ union—turned their backs on NYC Mayor Bill DeBlasio. It likely won’t be the last.

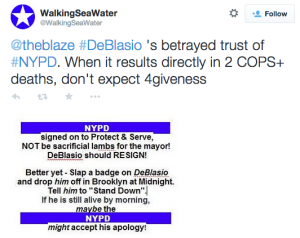

Some officers turn their backs to Mayor de Blasio at the funeral of Officer Liu. Photos: http://t.co/UWdLlxgo6g pic.twitter.com/4VFgTrzRFW

— Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) January 4, 2015

Since the tragic murders of officers Liu and Rafael Ramos, the New York City Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (NYCPBA), led by fiery president Pat Lynch, has said the mayor was complicit in the slayings of Liu and Ramos, distributed a petition asking de Blasio and Melissa Mark-Viverito (speaker of the New York City Council) not to attend funerals of officers killed on duty, and allegedly supported a citywide work slowdown.

The union insists its actions are spontaneous responses to a lack of support from the mayor and his political allies, as well de Blasio’s suggestions that the “Black Lives Matter” protestors (who the NYCPBA view as “anti-cop”) have valid complaints. However, the union’s actions are part of an old playbook of power politics with much bigger stakes. The NYCPBA’s strategy is not unique to New York: in its form and deployment, it’s indicative of how law enforcement leverages a distinctive societal position to exercise power in U.S. politics.The Issues at Hand

The spat between de Blasio and the NYCPBA began before the mayor took office. Candidate de Blasio made police reform—most notably, changing stop-and-frisk policies that disproportionately target African Americans and Latinos—a central plank of his campaign. He also said he supported a city council bill to make it easier to sue the NYPD for discrimination and another to create an NYPD inspector general to independently investigate police abuse.

Once elected, Mayor de Blasio made good on his campaign promise to accept a court decision that declared stop-and-frisk unconstitutional without judicial appeal. His administration also instituted reforms including making some cops wear body cameras.

When de Blasio hired an aide of Reverend Al Sharpton (a longtime nemesis of the NYCPBA and other police unions) as the chief of staff for the city’s first lady, Lynch’s union fumed. The aide had once been romantically involved with a man with a criminal record who had made derogatory comments about police on social media.

Other sources of conflict include de Blasio’s refusal to support legislation to improve officers’ pensions and to approve a new contract for rank-and-file officers (the two sides reached an impasse and the matter is now before an arbitrator).This escalating conflict between the civil power of the mayor and the bureaucratic power of the police defined the landscape of events that unfolded rapidly after the Staten Island district attorney decided not to issue an indictment in the Eric Garner case. De Blasio indicated an understanding of—if not support for—the thousands of people who took to the streets demanding police reform. At a church in Staten Island, the mayor said:

This is profoundly personal for me… Chirlane [McCray, my wife] and I have had to talk to Dante [our son, who is biracial] for years, about the dangers he may face. A good young man, a law-abiding young man, who would never think to do anything wrong, and yet, because of a history that still hangs over us, the dangers he may face—we’ve had to literally train him, as families have all over this city for decades, in how to take special care in any encounter he has with the police officers who are there to protect him…

This is now a national moment of grief, a national moment of pain, and searching for a solution, and you’ve heard in so many places, people of all backgrounds, utter the same basic phrase. They’ve said “Black Lives Matter.” And they said it because it had to be said… it should be self-evident. But our history, sadly, requires us to say that Black Lives Matter.

NYCPBA President Lynch responded quickly and forcefully, announcing to the press, “What police officers felt last night after that press conference is that they were thrown under the bus.”

When asked about de Blasio’s comments about talking to his biracial son, Lynch responded:

He spoke about, we have to teach our children, that their interaction with the police, and that they should be afraid of New York City police officers. That’s not true. We have to teach our children, our sons and our daughters, no matter who they look like, to respect New York City police officers. Teach them to comply with police officers, even if they feel it’s unjust. That police officers are protecting them from the criminals on the street. That’s what we do. Our city is safe because of police officers. All our sons and daughters walk the streets in safety because of police officers. They should be afraid of the criminals. That’s what we should be teaching them.

Addressing the public, Lynch said de Blasio’s fueled “anti-police” sentiment and that sentiment contributed to the murders of officers Liu and Ramos. The statements left little doubt about how Lynch felt the dots should be connected: the mayor had “blood on his hands.”

An Old Playbook

The NYCPBA’s actions have struck many as a unique police response to a highly unusual set of circumstances. In most respects, however, the NYCPBA’s response has been quite conventional. It reflects the distinctive political position occupied by law enforcement and the particular opportunities that position creates for political leverage in moments of heightened policy conflict.

The NYCPBA’s tactics fit well within a model of political action that’s popular among some of the nation’s most influential law enforcement unions—and, somewhat ironically, draws heavily from renowned community organizer Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals. I learned about this playbook during my ten-year study of the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA), the extremely powerful and successful union that represents prison officers in the Golden State (see also recent news stories about New York City’s Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, which represents officers who work in the city’s jails). Through “taking out” politicians electorally and shaming state officials, the CCPOA spread fear throughout the state capitol and Department of Corrections headquarters. The “specter of the CCPOA” helped the organization gain and maintain a privileged position in the halls of power.

Around 2004, the CCPOA opened up its playbook to confront Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and the Secretary of Corrections Roderick Hickman. Breaking tradition, the governor and secretary labeled the CCPOA a “special interest” and suggested the union supported a “code of silence” among corrupt officers, obstructed prison managers, and limited reforms necessary to deal with the state’s prison overcrowding crisis and mismanaged penal facilities. Schwarzenegger demanded that the CCPOA accept contractual changes that would decrease the union’s influence over prison policy, and he supported prison privatization (anathema to the union).

As it launched its offensive, the union flew a pirate flag from its headquarters. It paid for large billboards that literally depicted Schwarzenegger as the devil. They put a picture of a smiling Hickman on milk cartons, declaring the secretary “missing:”

Last seen running for cover after promising to clean up the mess at CDC, leaving line officers and department personnel to twist in the wind. Often found hiding under his desk in classic duck-and-cover fetal position. If found, please return to duty—or early retirement. REWARD—10,000 Rodney Bucks.

“Rodney Bucks” were play money the union created to mock Hickman. They deemed the secretary incompetent (“not worth a buck”) and suggested he’d sold out rank-and-file officers for personal gain.

With allies in the state legislature (including a former CCPOA member), the union then orchestrated public hearings that blamed Hickman for a murder of a correctional officer by an inmate. “I’m sticking it to him all of it on him,” said CCPOA President Mike Jimenez:

He’s the one calling the shots. When you get to the institutional level, the message is being sent to us that there’s a green light on staff. If an inmate complains on anything we do, it’s immediately investigated. If we complain, it’s malfeasance. They’re making us the bad guys, and this is something that is being handed down from the top.

Hickman resigned in 2006, saying, “The biggest problem that I had was the relationship I had with the union.”

When Hickman left office, the CCPOA continued its campaign against Schwarzenegger, going so far as starting (but ultimately abandoning) a campaign to recall the governor from office. The union sought to shame the governor in commercials, such as one featuring grainy images of inmates fighting on a prison yard. In a deep, portentous voice, the narrator says,

Overcrowded, underfunded, violent. California’s prisons are in meltdown. The governor’s response? He cut rehabilitation, officer training, prison safety. Now nine officers a day are being assaulted. When a federal judge threatened to takeover California’s mismanaged prison system, the governor said, “I don’t care. He can take it. It’s no sweat off my back.” That’s not a solution, governor. It’s a cop out.

A year earlier, in 2005, the CCPOA had funded a commercial starring leaders of Crime Victims United of California (CVUC)—an organization the union helped create and fund, then used to give its political tactics a sympathetic face—that argued the governor and his “parole reform plan” were anti-crime victim and anti-public safety.

Nina Salarno-Ashford, CVUC: My sister Catina was murdered (gun shots and sirens in the background). Shot to death by an ex-boyfriend. No mercy, no remorse. He watched football on TV after killing her. But because of Governor Schwarzenegger’s new parole policies, Catina’s killer could be back on the street. The calls it reform. I call it dangerous.

Narrator: Over 2,500 parole violators remained free last year under the governor’s plan. Over 2,000 went to commit serious new crimes.

Harriet Salarno, CVUC: You promised to stand with victims, governor. You let us down.

Ultimately, the CCPOA’s offensive was somewhat effective. Along with Hickman’s resignation, Schwarzenegger’s Administration toned down its rhetoric about officer abuse of inmates and abandoned the “parole reform model” CCPOA disdained.

But the campaign also produced a forceful backlash that ultimately harmed the union and forced a change in tactics. The Schwarzenegger Administration refused to budge on contract demands. The editors of the state’s major newspapers, a federal judge, and Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy all tarred the union as self-interested and against the public good.

In this public relations crisis, the CCPOA came out of attack mode and showed support for reforms to solve the state’s correctional crisis. In recent years, the California union has largely refrained from the type of political activity we’re now seeing in New York.

Back to New York

Law enforcement unions like the CCPOA (at least in earlier years) and NYCPBA use several core tactics to achieve political ends.

First, they employ the moral authority of the badge to brand critics—especially political officials—as anti-cop and anti-public safety. Efforts to change the terms of policing or ensure public accountability are framed as attacks on the honor and service of “the good men and women” who put their lives on the line for us all.

Second, they play into public fears about crime, victimization, and general instability. Because police officers are the “thin blue line” standing between civilization and violent anarchy, all of us (not just the police) are threatened by public officials’ misguided actions. That is, the police are not self-interested, but are standing up for the very public that elected officials claim to represent.Finally, they deny that their campaigns are fundamentally political.

The NYCPBA’s actions are not only the product of deep anger over de Blasio’s rhetoric and his administration’s actions. They are also calculated efforts to send a clear message to current and future political leaders: oppose the NYCPBA and risk political ruin.

The union (specifically, President Lynch) is effectively giving de Blasio and his allies the same advice he said he’d give the children of New York: respect officers and comply with their demands, no matter what. Showing police officers respect, in this view, means not empathizing with NYPD’s critics, not calling for reforms that NYCPBA opposes, and not bucking the union’s efforts to gain a new contract and better pensions.

As I documented in California, the politics of humiliation can be effective, but they can also backfire. Recently, newspapers, especially The New York Times, have been very critical of the NYCPBA. Non-police unions in New York City are considering breaking with the cops’ union. And de Blasio and police chief William Bratton seem increasingly committed to standing firm against Lynch’s demands.

The union and its rank-and-file officers may face blowback of a different kind. The current work slowdown (more precisely, change of priorities) may lead the public to feel less protected, and they’re more apt to blame the police than the mayor for declining police services. More problematically, Lynch’s “wartime” rhetoric and his complete disregard and disdain for protestors’ and their messages may further erode trust between communities of color and the NYPD, making officers’ demanding jobs even more difficult and dangerous.

Joshua Page is a sociologist and criminologist at the University of Minnesota. His first book, “The Toughest Beat”: Politics, Punishment, and the Prison Officers’ Union in California, won the 2011 Herbert Jacob Award from the Law & Society Association.

Comments 7

The Shame Game: New York City Cops’ Union and Power Politics - Treat Them Better

January 8, 2015[…] The Shame Game: New York City Cops’ Union and Power Politics […]

Sharon Bettis

January 11, 2015Great exploration and interpretations, Josh.

vxxc2014

January 11, 2015I think you are missing the point Sir.

The NYPD 12/21 Killings were Politcal Killings incited and encouraged from the Top of our Government, not just the hapless DeBlasio, but the President and his Attorney General.

Politics is Power, and this is a Political Struggle for the Plenary Police Powers which are held locally.

Not a Union Contract negotiating tactic, as your article implies.

vxxc2014

January 11, 2015"Political Killings"

The Shame Game: New York City Cops’ Union and Power Politics | Public Philosophy Journal

January 11, 2015[…] For the full article, see: The Shame Game: New York City Cops’ Union and Power Politics […]

ChristopherRigby

April 15, 2020Context is a website that includes sociology for the public and their departments. It has recent features of editor, books and also get help from https://do-my-assignment.com/do-my-homework-australia to solve your quality task easily. It has a context blog of the COVID-19 pandemic during the families which suffer a lot. Check their website for more information.

To Defund the Police, We Have to Dethrone the Law Enforcement Lobby

July 4, 2020[…] kids in harm’s way by making child porn a bail-free crime.” Not only will this lobby use public shaming against its political opponents, but also against colleagues who won’t fall in line. Police […]