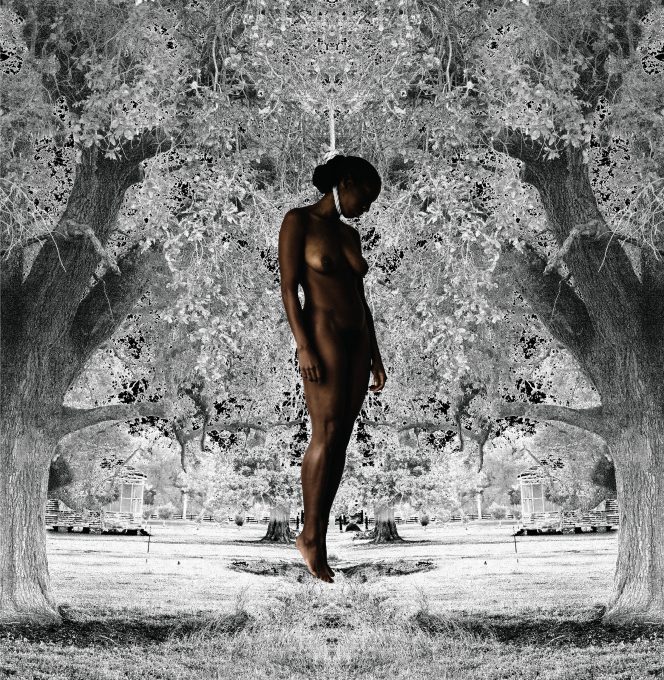

Ayana V. Jackson. "Moments of Sweet Reprieve," 2017.

Broadening the Landscape of Blackness, An Interview with Ayana V. Jackson

In the ongoing and profound expansion of possibility in the visual landscape of Blackness, photographer Ayana V. Jackson brings a critical, aesthetic edge that is at once arresting, alluring, and generative.

Using her own body to appropriate and re-stage “reference images”—archival photographs from colonial Africa and contemporary photojournalism—Jackson engages in a sustained critique of conventional notions of Black femininity. In her 2017 video work “Compared to What?”, Jackson quotes performance artist Nora Chipaumire in reminding us that her intersectional status has “historically been on a ‘collision course’ with power, masculinity, and Whiteness.” Colonial documentary photographs capture the violence of that collision, with racialized images of women, men, and children as submissive and suffering. The artist herself appears in the restaged reference images, clothed, semi-clothed or naked, and figured variously as a bound captive, swaggering guerrilla fighter, prim missionary teacher, and as a corpse swinging from a tree. Across this body of work, Jackson directs the aperture to interrogate certain kinds of racialized thoughts and their origins in photography.

Jackson earned her BA in Sociology from Spelman College, and now divides her time between Johannesburg, Paris, and New York. I met up with Jackson in Chicago, where select works were presented in the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s In their Own Form: Contemporary Photography and Afrofuturism, to discuss her work.

Fiona R. Greenland [FRG]: One of the observations you’ve made about your work is that the history of photography is complicit in the construction of racial stereotypes. Crude stereotypes about Black and Brown people existed prior to the invention of photography, of course. So what do you see as the particular contributions of colonial-era documentary to racial stereotypes?

Ayana V. Jackson [AVJ]: The advent of photography coincides with the middle of the colonial experiment. Images taken between the late 19th century and the early 20th crystallized the presentation of Black and Brown bodies as societies in need of civilizing. In order to justify the horrific acts of the colonizing process, there was a vested interest in presenting the non-White body as inadequate, grotesque, and alternately violent and violated. Photography took a broad set of stereotypes and distilled them into visual motifs, which were then reproduced and disseminated. Archival photographs, especially originating in colonial missions and, later, popular imprints like National Geographic, had particular authority because they were presented as official documents.

It’s important to remember, too, that access to photographic equipment was limited, and those on the other side of the lens were often not in a position to answer back with their own images. There was no first-person perspective to compare the colonial gaze against. So yes, the photographic medium was activated as a tool to illustrate problematic and often erroneous stereotypes that long existed in the Western psyche. These were images that set in motion the propagation of certain ideas about non-Whites, which proved remarkably and disturbingly intransigent. These are the kinds of images that lead us to see Africa as a dark continent where nothing good has happened. This is a powerful stereotype even today.

FRG: As you planned the re-staging of your reference images, you made the decision to include your own body as the subject. In some cases, this has meant positioning yourself in horrific moments of victimization, such as “Death” (2011), in which you hang from a noose on a grayscale tree, and “Dis Ease” (2011), a re-staging of Kevin Carter’s “Starving Child and Vulture.” Why was it important to you that your own body be used in these images?

AVJ: I wanted to use the naked female form as a metaphor for violence. I use my body because one of my concerns about the medium of photography is that the artist tends to impose his or her ideas onto the subject of the photo. Because I’m dealing with images that are politically complex and problematic, I felt that I had to use my body. If I were to expose another woman’s body to the type of violent image that I’m dealing with, I felt that it would be too close to committing a violent act upon her.

FRG: I really liked something you said in your lecture at the In their Own Form show. You said that, while nostalgia is one aspect of your art, it is important that memory work should also allow us to “remember new things.” How does that idea play out in your work?

AVJ: Especially when it comes to historical documents, we often assume that the past is fixed. In doing so, however, we risk reproducing the arrangements of power that normalize White supremacist mythologies and therefore domination of non-White people. By confronting the archive, new systems of knowledge can be created. New knowledge can, and should, include new memories.

It is important to remember that Whiteness, like Blackness, is a construct. The history of photography proves this. National Geographic’s recent apology for their editing and assignment practices confirms this. However so much is left outside of the frame, especially for those of us who were relegated to only finding our presence in front of another person’s lens. Susan Sontag writes about this quite thoroughly in both On Photography and Regarding the Pain of Others.

FRG: You’ve said of your recent series that it offers a sustained critique of the over-representation of suffering: death, destruction, and dictatorships. Do you hope that viewers will look at your photographs and re-think the relationship between colonial power and suffering?

AVJ: These images are not really about the colonizers and the colonized, or West versus non-West, and isn’t really about reinforcing any of those binaries. They are about examining the origins of certain kinds of ideas, and particularly of certain kinds of misrepresentations. My concern is not just about how Europe or the West has been taught to see Africa, but also how we, as Black (or non-White) people, have been taught to understand ourselves through those lenses. In this sense, I’m interested in a conversation that is much bigger than colonialism—namely, a conversation about how we have all been mutually affected by the original sins of the reference images.

All images © Mariane Ibrahim.

Reproduced courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Abdi Gallery, Seattle, WA.