Digging for Mutual Cooperation

The small town of Buxton is in many ways typical of rural Maine.

Its narrow streets are lined with the hemlock forests that cover much of the state. Its residents are neither poor nor rich, and if it once had the raw and rustic aesthetic that Andrew Wyeth depicted in his famous paintings of the Maine countryside, it has since transitioned to the convenience of vinyl siding and blacktop driveways. In almost every way, Buxton is rural America. So it comes as quite a surprise that one of its many gable-roofed homes houses Watt Samaki, Maine’s one and only Cambodian Buddhist temple.

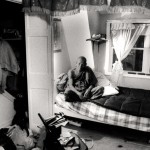

On a visit to the temple, I found Bak Him, an aging monk, digging a giant hole in the wooded area of the temple’s backyard. Never breaking from his work, Bak greeted me with a smile, then explained, in broken English, what he was doing. Move rock stones, dig pond, and parking were a few of the words I was able to make out. Saying little more, Bak continued to work using only his hands, a shovel, and a wheelbarrow to lift and pile stones that weighed several hundred pounds. After several hours, Bak’s pace began to slow. As sweat began to drip from his nose on a frosty October evening, he grinned at me and glanced towards my car. It was time for me to go.

Fleeing the Khmer Rouge, Bak Him escaped first to Thailand and the Philippines, and then arrived in the United States in 1986. For twenty years he lived with his family in Portland, Maine, spending much of his time volunteering in the community’s public garden. I met Bak in 2006, shortly after he’d become a monk and moved to the temple in Buxton. He had left his wife and the comforts of their family home in order to serve his community at the late age of 72.

I learned that Bak’s physical toil was part of his fellow Cambodians’ long and persistent efforts to integrate into the life of Buxton. At a recent town hall meeting, the Cambodian community had been ordered to construct a sizeable parking lot for their temple and a runoff pond for environmental purposes. Failure to comply would make subsequent gatherings illegal and subject the community to steep fines. In fact, the Cambodian community had been struggling for decades to establish a temple in the forest, like those of their homeland. Local Buxton residents—complaining about noise, parking, buildings codes and so on—had successfully petitioned to keep them out, forcing the community, for many years, to meet in a makeshift temple located in a small home in Portland. Exercising great patience, members of the Cambodian community remained confident that resistance would subside once Buxton residents became more familiar with Buddhism. Finally in 2008, the Buxton Planning Board approved the temple’s revised plans.

While distant policymakers may develop refugee policies, the conditions for successful integration are forged at the local level. The social cohesion that both refugees and locals seek comes only with the development of empathic relationships. Successful integration may be facilitated by an elderly Buddhist monk’s willingness to spend his days unearthing heavy stones, but it also requires host communities to keep their minds open and their hearts compassionate. This photographic portrait of Bak Him’s quiet labor in the woods of Maine is a call for mutual cooperation as the way forward in our increasingly connected world.