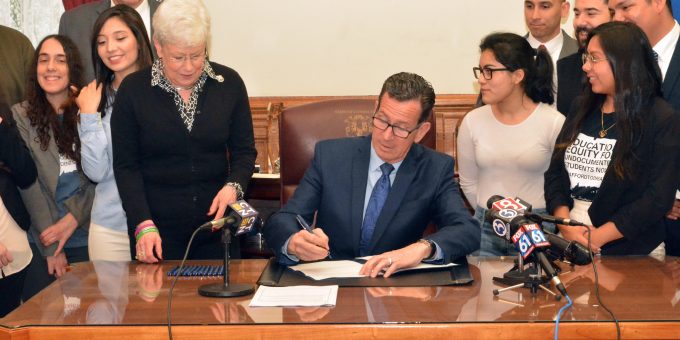

The governor of Connecticut signs a 2018 bill allowing Dreamers to qualify for state financial aid. Dannel P. Malloy, Flickr CC

Dreams Deferred

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was created by President Barack Obama in response to the failure of Congress to pass the DREAM Act, intended to protect undocumented people who were brought to the United States as children. DACA’s beneficiaries are colloquially known as the Dreamers, and the program was designed to help Dreamers work and go to school in the United States. Its authors fear, however, that its legacy will be marred by unintended consequences. In Demography, Amy Hsin and Francesca Ortega examine how DACA’s implementation has shaped Dreamers’ educational outcomes.

Finances figure into the barriers undocumented youth face in accessing and completing college degrees. Undocumented students, often first-generation college students, are not eligible for federal financial aid, may be expected to contribute to household income, and face uncertain returns from their education because after college, they may not be able to legally work in the United States. DACA allows Dreamers to apply for two-year work permits and provides protection from deportation, but is the program compatible with full-time education? The authors analyzed administrative data from a large university system that grants in-state status to undocumented immigrants who can verify their residency status. Unlike most datasets, this one allowed the authors to differentiate between undocumented and documented immigrant students.

Hsin and Ortega found that after DACA was enacted, there was a significant increase in undocumented, full-time, four-year college attendees’ dropout rates. At community colleges, undocumented students’ full-time standing decreased, but dropout rates remained the same. These findings underpin the authors’ claim that DACA incentivizes work over opportunities to increase human capital—in other words, DACA may be forcing students to choose between full-time school and work. While students can still obtain degrees by going to school part-time, neither choice fulfills the dream.