This demo game between Manchester United and FC Barcelona at Washington, D.C.'s FedEx Field drew over 81,000 fans. Mobilius in Mobili, Fickr CC. https://flic.kr/p/a8HZ6x

English Soccer’s Mysterious Worldwide Popularity

The English Premier League recently signed an $8 billion contract with two cable channels, allowing them to broadcast games from 2016–2019. And this staggering sum is only for the domestic broadcasting rights. The league will generate another $5 billion over the same period from international TV deals. The EPL is carried by 80 broadcasters in 212 territories worldwide, and an average game is watched by over 12 million people. With these astonishing numbers, the EPL has every right to call itself the most popular league in the world. In comparison, its closest rival, Spain’s La Liga, draws an average of just over 2 million fans per game. That league’s top two teams, Real Madrid and Barcelona, negotiate their own TV contracts since they are able to get more money from the global TV audiences than selling La Liga as a whole. Other top European national leagues also languish in comparison to the English league. Italy’s Serie A draws 4.5 million viewers for an average game and Germany’s Bundesliga is roughly 2 million viewers.Why is the EPL so popular worldwide? A number of theories have been floated but after close examination, we find that most prove to be no more than flimsy folk wisdom.

One theory is the passion of the players, commonly thought to be much higher than that of other European leagues. It is often remarked by commentators and pundits that English fans demand a higher intensity and work rate from their team’s players. As the former Manchester United player, current England assistant coach and Sky TV commentator Gary Neville recently said, “When people talk about the DNA of English football, we’ve got one: we work hard, we’re organized, structured, resilient, hard to beat, that never-say-die spirit.”

English fans have come to expect a high tempo, blood-and-thunder style of soccer, compared to the slower more technical European style making the Premier League a quicker, more open, more physical and more attractive game for international viewers. Yet, the proportion of English players in the Premier League has been consistently falling from over 70% in the inaugural 1992-93 season to 36% in the 2014–15 season with many technically skilled foreign players now playing in England.

Another common refrain from English soccer personalities is that the English league’s popularity is due to its highly competitive nature. It’s often heard that the EPL is the only league where “bottom can beat top” and where upsets happen at a much higher frequency than in other top European leagues. For instance, the former Chelsea manager and agitator extraordinaire, José Mourinho recently compared the EPL to La Liga, the league where he managed Real Madrid:

To go to matches knowing that you are going to win for sure is not the best thing. In Spain everybody knows that two teams are top of the world. But after that there is a huge competitive difference and that’s why the record is 100 points, 126 goals. In England, 100 points and 126 goals is impossible. If someone reaches 100 points and scores 126 goals, it’s not the best competition for sure, they can be the best team, but not the best competition.

These comments regarding the supposed higher competitive balance in English soccer often go unchallenged. But just how true is this narrative? One top British soccer writer, Jonathan Wilson, is not convinced:

It’s the most competitive league in the world. Anybody can beat anybody on their day. There are no easy games in this league. The mantra of the Premier League apologists is well known. …It’s nonsense, of course.

We sought to test these claims by examining results and final standings data from six top European soccer leagues from 1995–96 and 2013–14. The leagues are England’s EPL, Spain’s La Liga, Italy’s Serie A, Germany’s Bundesliga, France’s Ligue 1 and Holland’s Eredivisie.

When looking at the number of unique winners of these European leagues, it appears that no one team has dominated. For instance, in these 20 complete seasons, Bayern Munich and Manchester United have won their domestic leagues 12 and 11 times respectively, and Juventus and Barcelona have won the Italian and Spanish leagues 10 times each. Further, England has only had four unique winners during that time, Spain, Italy and Holland have had five, and Germany six. France’s Ligue 1 is the only league with more diversity—it had 10 different winners in 20 seasons.Examining winners may be too simplistic to come to any significant conclusion. Another way is to look at the diversity of teams in the top four places at the end of each season. From 1995–96 to 2014–15, the same four teams account for an astonishing 80% of EPL, 76% of Eredivisie, 68% of La Liga, 65% of Bundesliga, 65% of Serie A and 58% of Ligue 1 top-four finishes. In terms of unique top-four finishers, 16 different teams have finished in the top-four of Ligue 1 and 15 different teams in La Liga. Conversely, just 10 unique teams have finished in the top four of the EPL and Eredivisie. This analysis of the more successful sides in each league would actually suggest that the EPL is the least competitive league, while Ligue 1 is the most competitive.

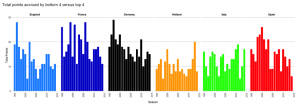

But perhaps focusing on the top teams is a too restrictive view of “competitiveness.” To get at the common refrain “anyone can beat anyone on their day,” a more appropriate analysis might factor in the performances of the weaker teams. To do this, we examined the success of the bottom four teams in each season when playing against the top four teams. We asked how many points the bottom four teams were able to accrue in games against the top four. The results can be seen in the graph above.

In each season, the bottom four teams play a cumulative total of 32 games against top four opposition—a win is worth three points and a draw one, making 96 possible points available. In no year, in any league, did the bottom four achieve more than 28 points against the top four. Notably, in the EPL, Bundesliga and La Liga, the significant trend is toward the bottom four teams performing far worse against the top four. France is the league with the highest number of seasons where bottom four teams achieved more than 20 points against top four sides—but even this league hasn’t had such a season since 2006. In Holland and Italy, the trend was fairly flat for a while, with the bottom four teams gaining on average only 10 points per season from their 32 games against top teams. Again, this shows there is actually some evidence that the EPL is becoming the least competitive in terms of these top-bottom matchups.

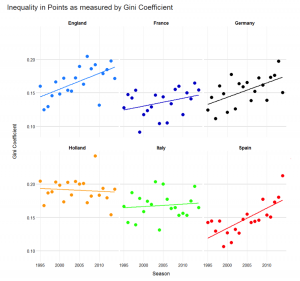

To get an even fuller picture of competitive balance, we can also look at the relative performance of all teams in a league in each season. To do this, we use a metric borrowed from the economics literature—the Gini coefficient. The Gini essentially describes the inequality in a group, and is often used to describe income inequality.

If the relative difference between individuals of incremental ranks in some outcome measure (e.g., points gained in a season) is generally equal, then the Gini will be close to zero. But if this outcome measure is distributed highly unevenly then the Gini too will be higher. The Ginis of each league from 1995–96 to 2014–15 are shown above.

In this figure, striking trends emerge. Since the mid-1990s, the Gini of three leagues (England, Spain and Germany) have been steadily increasing. This means that more points are ending up in the hands of relatively fewer teams—the leagues are becoming more unbalanced. Among these, the EPL has consistently been the most unbalanced. Ligue 1, for example, also shows a moderate tendency to becoming more unbalanced, but it is still much more equal in its points distribution than other leagues. The Dutch Eredivisie and Italian Serie A have historically been the most inequitable, though in the last few years they have been caught by other leagues—the EPL in particular.The EPL may well be the most popular in terms of worldwide audience, but, from our analyses, this is not because of “competitive balance” or “upset likelihood.” In actuality, a strong case could be made that all other leagues—with the possible exception of the Dutch Eredivisie—are far more balanced.

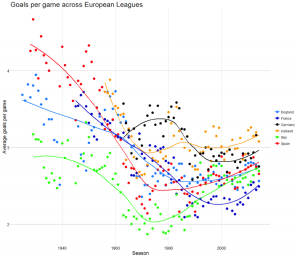

After our analysis the question still remains: Why is the EPL so popular? Perhaps it could be as simple as the league’s higher scoring. Fans love goals, after all.

While the EPL was historically a high-scoring league, it was never as high-scoring as the Spanish league. Over the last 20 or 30 years, the EPL is actually very similar in goals per game to La Liga. During the same period, the more competitive French league has relatively low scoring, whereas the less competitive Dutch league has been relatively high scoring.

It appears that the disproportionate popularity of the EPL may not be due to competitive balance, upset likelihood or high scoring. What’s more, the most competitive league—Ligue 1—is relatively unwatched outside of its own country. Equality certainly does not equal quality.

In fact, there must be a sweet spot of upsets and competitive balance. In all sports, dominant dynasties are generally popular. In the U.S., look no further than the recent histories of the Yankees or the Bulls or the Patriots. Fans—particularly global fans—like to associate with winning teams. However, if games and leagues become too predictable it’s possible that fans will lose interest.In the end, perhaps the answer to English soccer’s popularity lies beyond the database. Perhaps the key is in the aesthetics. The data disproves a few popular notions, but it can’t ultimately prove that it is the tumultuous physical nature of English soccer combined with the English fans’ vocal energies and fanatical loyalties to their clubs that makes the EPL the most visually appealing broadcast spectacle in the world.

Comments 2

Samuel Charles

March 19, 2016Great piece.

I've touched on the UCL and title disparities but I think this data about the competitiveness of lower teams is far more interesting, or at least newer to me. With that plausible and un-rebutted argument has been re-cycled forever, you come bearing fresh ammo!

Other reasons for Prem's popularity: People like the fact the Premier League presents itself as the only thing that matters, even experts can't keep track of all of Europe, but fans can feel informed about 20 clubs (presentation of Prem closer to NFL/NBA model). It's the only top league in an English-speaking country (emphasis on English, and the sugar-high addiction that is broadcasts in Brit-patois). It's become the global language, and demographics of English speakers were always more influential/wealthy. The first live soccer TV broadcast happened in England in 1937, Match of the Day first aired in 1964, aka the English perfected presenting their product before other countries even got their pants on, and no one does a better job of making trivial encounters on Tuesdays at Stoke seem vital to the course of human history like the Prem.

Nice work, thank you!

ps

If Leicester wins, it will be the first time any city outside Manchester or London celebrates a Premier League title since Blackburn won in 1994-95. And. Over the last 11 seasons just five clubs have claimed 43 of the 45 Champions League berths: Arsenal, Man U, Man City, Chelsea, Liverpool. (Everton in 2005 and Tottenham in 2010 are the only exceptions.)

doug

March 25, 2016you missed the metric that matters: payroll. The EPL has the highest payroll.

My second suspect stat: English commentary and the English language. The German league has a huge number of eastern European players with "unpronounceable names" compared to the other leagues.