Young Women of Color and Shifting Sexual Identities

Last spring, one of us was talking with a heterosexual, African-American male friend who said he’d been surprised to learn that his niece, Amani, whom he believed to be straight, was thinking of inviting a girl to the prom. Amani did not identify as lesbian, but hinted that she “might be bi.” Her uncle wondered whether Amani had always felt she was LGB or whether her declaration was part of some new trend among young people, perhaps “thinking outside the box” when it came to their sexualities.

Indeed, Amani is among a growing number of young women of color who self-identify as bisexual or lesbian. But what this trend means for her and other women like her is complicated by how sociologists often measure and make sense of sexual minority identities.

Consider a question that sounds deceptively simple but has motivated a great deal of scholarship: “How many gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are there in the United States?” Estimating the size of sexual minority populations is challenging for a collection of reasons related to Amani’s statements. Where does Amani “fit” in the current social landscape of sexual identities? Would everyone encountering her story understand her sexuality in the same way? How will Amani ultimately decide to sexually identify? And will that identity stick, or might it continue to change over the course of her life?

In a 2017 essay in Contexts, Amin Ghaziani explored the issue and difficulty of measuring sexuality and who to “count” as gay, straight, or anything else. Studying sexuality demographically depends on our ability to extract information from respondents that some may not want to share. We can ask survey questions about dimensions of sexuality, and when we do we receive wildly different estimates. Sometimes this has to do with how sexuality is being defined. Sexualities are composed of (among other things) desires, acts or behaviors, and identities. And while one might expect people’s sexual desires to influence their sexual behaviors and the sexual identity they claim, the sociological fact of the matter is that these dimensions do not always line up neatly (as research since Laumann, Gagnon, Michael and Michaels’ The Social Organization of Sexuality has borne out). People may engage in sexual practices at odds with their sexual desires or lay claim to sexual identities that do not reflect their sexual practices. And not everyone understands sexuality and their own sexuality(ies) in precisely the same ways. Sexualities are far more flexible than we often embrace (see, for instance, Lisa Diamond’s Sexual Fluidity and Jane Ward’s Not Gay).

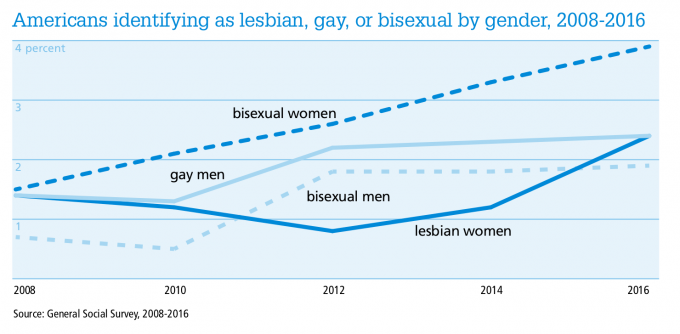

Existing research and survey evidence has shown that asking about same-sex sexual identities, as opposed to same-sex behaviors or desires, yields the most conservative estimates of the size of the LGB population while also showing that sexual minority identities are growing rapidly among young adults. The General Social Survey has included a question about sexual identity since 2008, asking respondents to classify themselves as “gay, lesbian, homosexual,” “bisexual,” “heterosexual or straight,” or “don’t know.” Between 2008 and 2016, those identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual rose from 2.7% to 5.4%—a 100% increase in just eight years. The distribution within these identities has changed, too. In 2008, more people were identifying as lesbian or gay (1.6%) than as bisexual (1.1%); by 2016, bisexual had become the more prevalent sexual minority identity at 3% of respondents (compared with 2.4% identifying as lesbian or gay).

The greatest shift occurred among women identifying as bisexual. The figure above reveals shifts among lesbian women, gay men, and bisexual men alongside bisexual women. Between 2008 and 2016, the percentage of women classifying themselves as “bisexual” more than doubled, from 1.5% to 3.9%. Bisexual women represent the largest change in sexual identification over time, and, among women, bisexual is now a more prevalent identity than lesbian. Among men, however, bisexual is less popular as a sexual identity than gay. This is important because, as D’Lane Compton, Nicole Farris, and Yu-Ting Chang showed in a 2015 article, as a sexual identity category, “bisexual” is often presented as more nebulous than lesbian, gay, or straight classifications.

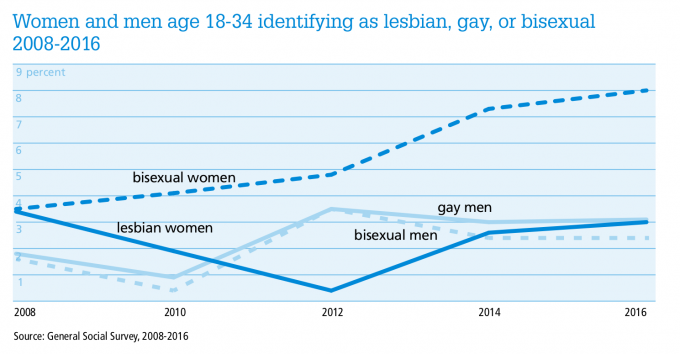

The next figure, above, shows that the change in women’s bisexual identities is largest among the youngest age group, which—as Amani’s uncle suggested—is also the group for whom sexual minority statuses more generally are the most common. Between 2008 and 2016, the proportion of 18 to 34-year-olds identifying as lesbian or gay increased modestly, from 2.7% to 3.0%. Over the same period, the proportion of these young Americans identifying as “bisexual” doubled, from 2.6% to 5.3%. And broken down by gender, the proportion of women in this age group identifying as “lesbian” actually declined (from 3.4% to 3.0%) while the proportion identifying as bisexual more than doubled (from 3.5% to 8.0%) in the same period. Among this age group, there are almost as many bisexual-identifying women as there are gay men, bisexual men, and lesbian women combined!

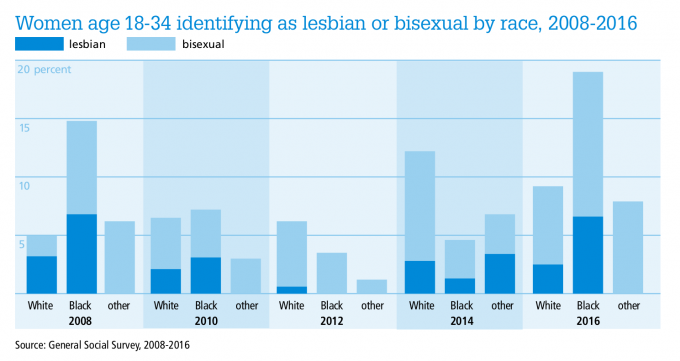

We can further comprehend the complexity of shifts in the LGB population when we consider race. While many surveys find no statistically significant differences in the racial/ethnic composition of LGB adults and non-LGB adults, one of the largest nationally representative surveys collected by Gallup and analyzed by Gary T. Gates in 2014 reported that LGBT adults were less likely to be White when compared with the non-LGBT population. Consistent with the GSS data presented here, Gates showed larger differences by race among young people. Whether this is a cohort or period effect is not clear here.

The GSS collects a much smaller sample and does not specifically over-sample for sexual minority identities. Yet, it is clear that Black women are a disproportionately driving the shift toward young women identifying with bisexuality. As the first figure above shows, just shy of one in five 18- to 34-year-old Black women in 2016 identified as a sexual minority (12.4% identified as “bisexual” and 6.6% identified as “lesbian”) in addition to how this has changed since 2008. We are cautious, because generalizable claims become difficult when sample sizes shrink after cutting the population across different axes of identification. But the figures support Gates’s 2014 analysis of Gallup data suggesting that LGBT adults are increasingly less likely to be White than are non-LGBT adults. Black women account for the majority of this increase. (Sadly, the General Social Survey has asked this same question on race since they began administering the survey. Data for racial groups beyond Black and White are collapsed into a single category—“other race.”)

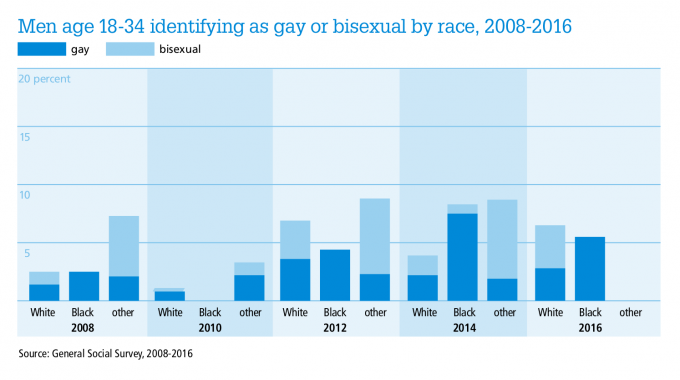

More men have identified as “gay” or “bisexual” over time, but the pace of change has been slower. But growth has been much slower here. Additionally, bisexual identities are much less common than gay identities among both Black and White men (which is opposite to the trend we discussed above among women). In 2016, Paula England Emma Mishel, and Mónica L. Caudillo analyzed a similar shift in same-sex sexual behavior using the National Surveys of Family Growth data. They showed that same-sex sex has become more common among both women and men, but the increase has been much steeper among women. They argued that this pattern is broadly consistent with androcentric and asymmetrical shifts in gender inequality, wherein departures from normative gender behaviors are seen as more acceptable for women/girls than for men/boys.

These data suggest that a great deal of the changes in who is identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual are happening among young, bisexual women of color—Black women in particular—and they reflect both our measures of sexualities and changes in how people respond to those measures. As laws and social stigma shift surrounding same-sex desire and sexual identification, we may see new and greater populations of people, like Amani, sexually identifying in ways they have not in the past. Sociologists studying sexualities have to always remember that the very object of their study is “on the move.” This fact underscores the need for more and ongoing research with these groups to better understand their experiences and identities and how they change. We will continue to learn more about how members of these groups reflect, reveal, reinforce, and resist existing forms of inequality that continue to shape the lives of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people.

Demographic trends offer one way to begin to understand experiences like Amani’s. Like any window into the social world, however, the view from a demographic perspective will always only be partial. The most effective sociological analyses of these issues will require mixed-methods approaches that simultaneously qualitatively measure how individuals think about dimensions of sexuality. And we must continue to speak across methodologies as we seek to make sense of new shifts and discoveries. For instance, qualitative analysis of interviews with women of color over time might shed light on the processes through which they understand their sexuality, take on new sexual identities, and experiment with or experience different sexual identities over time. Research like Mignon R. Moore’s Invisible Families: Gay Identities, Relationships, and Motherhood among Black Women and Katie Acosta’s Amigas y Amantes: Sexually Nonconforming Latinas Negotiate Family help fill in the gaps and capture the changing ways these groups feel limited by and work to extend existing sexual identities and labels.

After all, for Amani, inviting another girl to prom did not necessitate “coming out” as lesbian or bisexual. It made her suggest that she “might be bi.” We can learn more about, and from, women like Amani about how sexuality intersects with gender, race, ethnicity and age to better understand the shifting landscape of sexual identities and contemporary systems of social inequality.